We all want a peek behind the curtain. We’re wired with almost primal curiosity about those aspects of an endeavor that we’re not supposed to see – the magician preparing his tricks, the athlete doing his warmups.

In music, the off-limits spaces include the practice room and the composition studio. These are not always happy places. To an eavesdropper, what’s going on behind the door might not sound the least bit musical. Here, the artist confronts shortcomings in his or her approach to the nuances and the mechanics of the art. Here, the illusions are stripped away, the bad habits put out to pasture, the roadblocks decimated brick by brick.

Music publishers have long exploited this curiosity about what big stars do in the practice room; in the decades since jazz became an area of academic study, there’s been an explosion of books designed to help aspiring improvisors. Some offer method-book-style phrases and patterns, or transcriptions of famous solos. (Alert readers of this space may recall a short riff on The Practice Notebooks of Michael Brecker, which breaks down how he developed his musical vocabulary.)

The Notebooks of Sonny Rollins, cannily edited by Sam V.H. Reese and published last month by New York Review Books, is not this type of document.

Though it contains thoughts about the alternately granular and mystical work of growing as a musician and improvisor, it’s nothing like a how-to book. It offers no step-by-step process a student might hope to follow. Instead, it’s a real-time account of an artist immersed in his own necessarily idiosyncratic process.

And because these journals contain the interior thoughts of an artist who is, on a daily basis, examining what it means to be alive and immersed in developing one’s abilities, it’s a sprawling concatenation. Rollins makes lists, admonishes himself when his spirits are low. He observes what he doesn’t like about jazz clubs, jots reminders about having good form while exercising. He examines every aspect of tone from the intake of breath forward, reminds himself of the tactics that worked on previous days when practicing particularly tricky saxophone fingerings.

“Don’t deviate from one idea to another when practicing,” Rollins writes in the first section, The Bridge Years, which covers the period that began after his 1959 European tour and ended in 1961 – when the saxophonist’s preferred practice room was the Williamsburg Bridge. “When you hit upon something that needs doing and you are receptive to doing this, stick on that.”

That’s followed by more thoughts on maintaining focus, and then one of many notes on posture: “Hunch-raise left shoulder high to bring freedom to lungs.”

This book is unlike anything else in the entire written discourse about improvised music. It can be read as a treatise on the sprawling, challenging-to-maintain (and alas now receding) concept of discipline itself, as its own goal. It’s also concerned with the long-game pursuit of voice, and at the same time, it’s about mental and spiritual clarity. One minute Rollins is scrutinizing his approach to chord sequences and then next he’s contemplating music as a unifying energy. “Who can deny that the greatest of any music is of a one-ness which transcends period, style, country, etc….any definition which seeks to separate Johann Sebastian Bach from Miles Davis is defeating its own purpose of clarification.”

Then, later on that same page: “Jazz is a vigorously hybrid product which is All American….It is the music of America created by Americans for the edification of all mankind.”

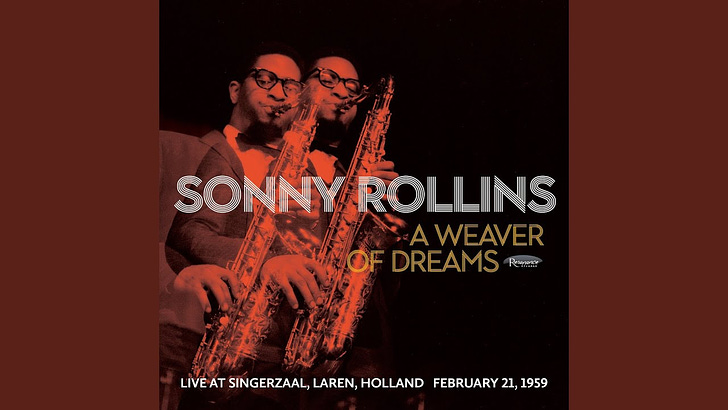

By cosmic coincidence, The Notebooks of Sonny Rollins arrived within weeks of Freedom Weaver, a marvelous collection of live recordings from the saxophonist’s 1959 European tour. (It was discussed in this Record Store Day version of Echo Locator.) Rollins was an established if not revered saxophone voice at the time, and these recordings show why: He executes wildly daunting, gregarious phrases with watchmaker precision. He breezes through tunes at wickedly brisk tempos, rarely sounding like he's bothered by any technical concerns at all. He’s the embodiment of flow.

And yet, after this tour, Rollins evidently wasn’t satisfied. Unaffected by the reverence showered on him from critics and listeners, he stepped away from public performance to embark on one of the several quests of self-discovery that dotted his long career. His journal writing began right here, and as his powers of observation sharpened, he undertook sustained reflection on the paradoxical nature of his work. Reading his notebooks, we learn that the sound of freedom that’s so alive in his music was attained by unglamorous, intentional and often grueling discipline.

***

The record producer Michael Cuscuna, who died last week at age 75, was one of the first – and arguably the best – to pull back the curtain on the history collecting dust in the jazz vaults.

The label he co-founded in 1982, Mosaic Records, established the gold standard for archival releases at a time when the major labels regarded old music as a sleepy aspect of the business. Mosaic celebrated some big names – compiling a 9-disc box of recordings the Ahmad Jamal Trio made for Argo Records in the late ‘50s – yet treated works by overlooked talents, like the pianist/composer Sonny Clark, with the same respect. The label’s meticulous audio restorations brought clarity to vintage recordings that were often not tended properly, and its limited edition boxed sets offered spectacular photographs and passionate, context-rich notes and essays.

Cuscuna played a major role in the 1985 relaunch of the storied Blue Note label, overseeing expanded versions of classic records as well as the release of an astonishing number of quality LPs that had been recorded during the heyday of hard bop but never released. In the ‘90s, he masterminded Columbia’s comprehensive reissue program of Miles Davis’ catalog, culling previously unreleased live recordings and outtakes.

I spent a week with Cuscuna and his co-producer, Bob Belden, as they were poring through the session reels featuring Davis’ ‘60s quintet. It was research for a story on the Davis archive for Musician magazine, which, unfortunately, folded just as I was finishing a first draft. Working in a small studio on 10th Avenue in Manhattan, the two would listen to everything – even false starts and incomplete takes – to locate previously unreleased material that might merit inclusion in a boxed set.

When I arrived, they were doing E.S.P., from 1965. A legal pad in front of him, Cuscuna sat making notes on the alternate takes – even taking down the banter between Davis, the musicians and the producer Teo Macero in the control room. They intended to use some of those back-and-forth exchanges in the boxed set, and Cuscuna, who was known for his droll wit, was frustrated by Davis’ famous whisper. “Why’s he whispering like that?” Cuscuna demanded in fake outrage. “We can’t use this. Barely audible! Doesn’t he know it’s part of history?”

Such important work. The original output was probably designed to be streamlined for 20 minutes a side. Not so much history but of course now in retrospect it’s incredibly important as history. It’s really amazing that you were there during that process.