Objects in Rear View May Be Larger Than They Appear

A Whirlwind Survey of Record Store Day Highlights

As it has grown, Record Store Day — a twice-yearly initiative that began in 2007 to celebrate the unique cultural role of independent music retailers — has sprawled into an industry of its own. Some small labels schedule the bulk of their releases to coincide with the event. Others wouldn’t even exist without it; they rely on the clever multi-tier marketing of limited-edition rarities to reach an elite audience of obsessives and cratediggers.

The success of RSD brings with it largely unspoken existential questions: Are we spending too much energy (and money!) gazing backward? Should the community of music people view the vibrant and ever-intensifying quest for vault rarities as an unalloyed positive? A contribution to history? Or does it, perhaps, tacitly confirm the oldhead bias about music being more substantial in days gone by?

There are no ready reconciliations for these questions — but watch this and other spaces, because we critics do love to undertake longwinded attempts at dissecting such vexations.

For the moment, the lineup for this festive Record Store Day — coming Saturday, 4/20! — fills 9 full pages, single spaced. Its list contains entirely new compilations, like The Rough Guide To Hoodoo Blues, which features Memphis Minnie and others, as well as new colored-vinyl editions of previously released compilations like the beloved the 2006 Studio One Rude Boy set. That one offers no additional tracks.

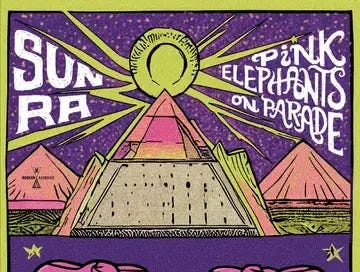

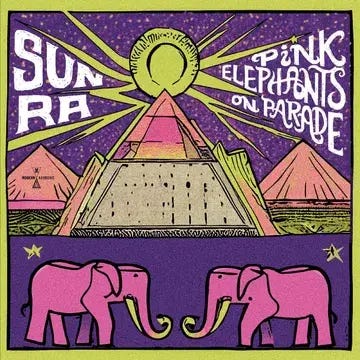

Arguably the most inspired bit of curation on this year’s list is Pink Elephants on Parade, which gathers nine live performances of the Sun Ra Arkestra engaged in bristling astral reimaginings of tunes associated with Disney films. The RSD description captures this delightfully: “When you wish upon a star… that turns out to be Saturn.”

The performances, like the galumphing title track above, are drawn from Ra tours in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, a period when the group was broadening its notions of spirituality and free-improvisation spaciousness; perhaps not coincidentally, the group was spreading its message by playing rock venues (“Someday My Prince Will Come” is one of several recorded at the 9:30 Club in Washington D.C.). Every track here is a balance of opposing forces: The group refracts the dewey-eyed Disney melodies with what often sounds like affection, then heads out for points unknown in the spaceways.

Of course that’s not the only Sun Ra title offered this year: The reissue label Jazz Detective has a two-disc set, At The Showcase: Live in Chicago 1976-77 from a strong and more riotous period of the Arkestra, when its ranks included tenor saxophonist John Gilmore and French horn player Vincent Chancey. The crisp audio gives a sense of how the large crew sounded in a room that typically hosted hard-bop quintets — and informative liner notes quote from trumpet player Ahmed Abudllah’s autobiography help set the scene, describing how the band was “miraculously squeezed onto what was called a stage.” The music bustles with brio throughout, particularly on the more ambitious works in band’s book like “The Shadow World,” which contrasts intricate ensemble passages with dramatic unaccompanied solos from Abdullah and alto saxophonist Marshall Allen.

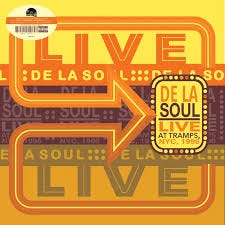

The many live titles of Record Store Day offer a particular lens into music as performance, underscoring the challenge of balancing audience expectations against the artist’s desire to keep material fresh. Example: This year brings a nicely remastered vinyl version of De La Soul’s Live at Tramps, NYC, 1996, which finds the trio weaving new stanzas and wisecracks to the familiar narratives of “Ego Trippin’” and “Me Myself and I,” and goading some special guests, including Mos Def and the Jungle Brothers, into high intensity ad-libbing. Play this for the friend who maintains that hip-hop is scripted.

For many jazz musicians, the stage is both proving ground and new-idea incubator. Day after day, improvising artists go to work in beautiful halls or less-than-opulent clubs, chasing phrases that might have eluded them the day before — or the set before. In order to focus on that type of development, many legendary figures would limit repertoire to a short list of tunes. Miles Davis played “Stella By Starlight” frequently in the 1950s and ‘60s; Sonny Rollins, whose knack for reviving underloved tunes has no peer, was partial to Jerome Kern’s “I’ve Told Ev’ry Little Star.”

On his 1959 European tour, Rollins evidently played that tune a lot — there are four (!) versions of it on the startling and exciting Freedom Weaver, a three-disc serving of colossal saxophone. The March 4 version of “Star,” in Stockholm, is taciturn and melody-centered; the next night in Switzerland, Rollins is more expansive, stretching into longer and more elaborate ideas; in Holland a few days later, he is cagey, stepping reverentially through the theme; the March 9 version in Germany is more playful, with Rollins adding antic squiggles and alternate-fingering sound tricks.

We don’t often get to witness this day-by-day dimension of the improvisor’s pursuit. All of Freedom Weaver is superlative — Rollins sounds at once in control of every attack and each slope of his phrases while gliding across the music, and imbuing it with a loose, freewheeling spirit. It’s not hyperbole to call this discovery an instantly essential document in the history of jazz tenor saxophone.

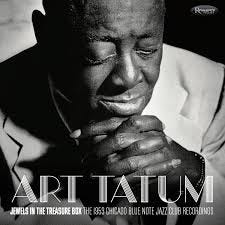

Similarly, Jewels In the Treasure Box: The 1953 Chicago Blue Note Recordings (Resonance) offers a chance to engage the genius of Art Tatum at close range. It’s a surprisingly crisp document, recorded live at Chicago’s Blue Note in 1953, that brings Tatum’s dazzling gifts into focus. The pianist — heard here with legendary bassist Slam Stewart and incredible guitarist Everett Barksdale (more on him in a future edition) – is usually celebrated as a ferocious technician, and there’s plenty of that on display across three discs. But on surprisingly unflashy renditions of “After You’ve Gone” and “Stardust,” what comes across first is Tatum’s bright, fluid sense of melody, his ability to real-time organize complex musical sentences into sleek, beautifully logical phrases.

Same year. Same club. Same piano. Different vibe: Live at the Blue Note Chicago captures Nat King Cole and his backing trio shortly before the pianist and singer ascended to stardom and left the clubs behind. It’s greatness on the runway: Cole does a few things from his “jazz” repertoire — “You Stepped Out of a Dream” sparkles — but the bulk of the material is songs he’d record over the next few years, like “Unforgettable” and “It’s Only a Paper Moon.” The vocals are riveting, but the surprise draw is the piano playing: Where the famous later versions of these tunes dwell in orchestrated opulence, Cole provides snappy, swinging and invariably apt accompaniment.

The last title in today’s RSD roundup is a previously unreleased 1966 solo concert by the pathfinding gospel-blues singer and guitarist Sister Rosetta Tharpe. By that point, Tharpe had played a whole lot of “Down By the Riverside,” and even more “This Train.” She’d been a road warrior since the late ‘30s, when she was part of the Cotton Club revue with Cab Calloway and a featured performer on John Hammond’s Spirituals To Swing concert at Carnegie Hall.

Here’s a “This Train” (with a tremendous guitar solo!) from France in 1964, the year Tharpe took part in the Blues and Gospel Caravan tour headlined by Muddy Waters. According to legend, attendees at the Manchester UK show included Keith Richards, Eric Clapton and Jeff Beck.

Think about that: This woman, whose fiery melding of gospel entreaties with blues riffs led directly to the birth of rock and roll, relied on a relatively small pool of uplifting, rhythmically varied, battle-tested songs — and performed them for rapt congregations and rowdier concert crowds night after night. For decades, through boom hitmaking times and lean years and an unlikely second coming sparked by concerts in Europe.

You can’t hear those road miles on the riveting Live In France: The 1966 Concert in Limoges. Instead, you hear the resolute tones of a woman who understood the demands of show business as well as the conveyance of something beyond commodity, something akin to pure spirit. You sense the galvanizing presence of a communicator who instinctively knew when to sing sweetly and when to put the hammer down, with the authority that comes from having done it for a long long time.