Notes on Process

Three Views of Secrets

There are many ways to look at all the vault sifting and historical document scrounging that’s been going on in recent years. Can the digging be read as a response to the current state of music creation? [This is the almost-automatic old-person default position, and it overlooks a ton of super-creative music happening right now, with or without aid from an “industry.”]

Maybe it’s a slow-rolling collective awakening to the awareness that there was a staggering amount of quality work happening in the popular music realm during the 1950s through the 1980s – and not all of it saw the light of day. That’s motivation enough to paw through boxes of 2-inch master tapes in dusty attics and storage facilities that may or may not be up to fire code.

When you start to pay attention to these discoveries, sooner or later it becomes clear that the act of creating and documenting musical ideas is not about waiting for fairy dust to land. Instead, it’s a process. One that involves hard work. And dedication to an abstract idea that may very well resist capture. It involves the willingness to try again when the first idea doesn’t connect, and try again when the second idea collapses, and again and again. The artists, songwriters and producers who contributed in a profound way to pop and jazz and really every genre treated the pursuit of audio inspiration as a job. They worked at all of it, from the fleeting idea phase to the arrangement-building phase to the last spark from the singer as the track fades.

You wonder: Do we think about it that way anymore? Have all the digital tools, all the processing shortcuts, changed something fundamental about this endeavor? Over time, does all the technological ease contribute to a form of artistic laziness?

That thought crossed my mind listening to Leon Moore’s tender piano and voice demo of “What Would I Do” from the altogether awesome Written in Their Soul: The Stax Songwriter Demos.

This massive 7-disc anthology was curated by a team including Stax songwriter Deanie Parker and Omnivore Records head Cheryl Pawelski, and covers not only Stax hits but songs written by Stax-affiliated writers that were hits on other labels. It focuses on the outlines and sketches used by labels like Motown and Stax to convince artists to record the songs. These sketches were seductions in themselves, and were then sometimes used by the artists as a turn-by-turn road map of how to interpret the songs.

Songwriting demos are, arguably, at the center of pop alchemy. At Stax they were sometimes no-frills affairs and sometimes full-band productions designed to offer “proof of concept” for the song. Listening to the tunes sung by their authors, you sense attention to the structure and any strange twists a singer might not expect. You feel the writers sharing something they believe in.

Moore starts with a brooding two-chord pattern that underpins the verses. Before he gets to the words, he sings a phrase he imagines a guitar might play – and this little childlike aside conveys the precise mood he’s chasing. Unlike some Stax hits, the song travels far from the typically sunny doo-wop chord pattern – it’s got a killer bridge, for one thing, and Moore leans into it like he knows what he has, how different it is. By the end, it’s easy to play armchair A&R and imagine a strong voice like Carla Thomas doing it, or maybe Donnie Hathaway, or…..?

This set, which is housed in a hardback folio and contains amazing in-studio photography, is aimed at people who are already somewhat familiar with the legacy of Stax, and also its deep team of songwriters. There are stirring performances from Carla Thomas and Eddie Floyd and William Bell (who often co-wrote with Booker T. Jones). Three discs (!) are devoted to unreleased songs, and these include dizzying funk from Rufus Thomas, prayerlike entreaties (“Coming Together”) written by Stax secret weapon Homer Banks, and stirring songs written and demoed by Mack Rice and Bettye Crutcher that make you wonder how such skillfully threaded songs like “Too Much Sugar For a Dime,” recorded separately by Banks and Crutcher, were ever left on the shelf.

STEELY DAN

Of course there’s a lost Steely Dan track from the Gaucho sessions. Or three. The legend goes that “The Second Arrangement” – which surfaced last week in a newly cleaned up version, after circulating as a noisy bootleg – was slated for the record, and inadvertently erased by an assistant engineer at the end of a mixing session. Of course said engineer was stoned at the time.

The tale, told on the excellent Substack Expanding Dan, involves a safety copy made by sonic wizard Roger Nichols and discovered after his death by his daughters. The band has allowed further sonic processing and a YouTube release of the track, which has the labyrinthine sequences of other Gaucho songs and a wickedly tart Donald Fagan lead vocal. If it wasn’t fully “done” – and what does that even mean where Steely Dan is concerned? – it is at least close.

The band attempted a re-do of the entire track, did it top to bottom and then Fagan scrapped it. You wonder how much that doubling-back effort changed things, and also about the fragile dynamics inside that studio: The brain trust, known obsessives who spent days in pursuit of the exact crackle from a snare drum, was deep in the tune at the moment it was lost.

Here we encounter a different phase of the process. Steely Dan was in the song business, certainly, but it was also devoted to a rare and delicate alignment between the “text” of a song and its sumptuous atmosphere. Becker and Fagan wrote mythologies-in-progress, glimpses into inaccessible realms with details intentionally missing and others oversupplied. As methodical as they could be in the studio, they were also hyperaware of suffocating the magic right out of a track. They knew when to let the groove advance the narrative. The act of having to re-do anything, from the ground up, might have sent the joy right out of the whole affair.

Another, less-complete outtake, presumably from Gaucho, suggests exactly this: “Kulee Baba” catches Steely Dan somewhere in the middle of the vibe creation, before the principals light the incense and activate the sparkle machine. The song’s structure is nailed. It’s super immediate and entirely interesting apart from the parlor game what-iffing that has attended these discoveries. Every instrument, every leering Fagan line, is part of the vibe. You can’t help but lament that this track, like “The Second Arrangement,” wasn’t finished to their satisfaction. And that’s all that matters, not whether either “belongs” on Gaucho. That ship sailed decades ago.

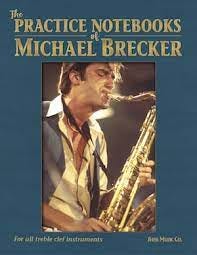

MICHAEL BRECKER

What does it take to develop facility as an improvisor? There’s mystery involved in it, for sure. Those stories of greats like Charlie Parker being scolded as they were learning the ropes speak to the challenges of the process, which involves learning language and understanding how to share that language in the moment, while upholding the rhythm and interacting with the musicians who are sustaining that rhythm.

Some jazz musicians did this completely by feel – never stopping to analyze a note or phrase in relation to a chord, never worrying about any under-the-hood details. Michael Brecker was not one of those.

A new book, The Practice Notebooks of Michael Brecker, brings us into the practice room where one of the most talented saxophonists of the modern era developed the building blocks of his craft. A quote between Books II and III is indicative of Brecker’s pursuit: “If I have an idea, I try to put it in every key. It try and get all over the horn....I have books and books of exercises that I’ve made up, but I don’t write the exercises out completely. I’ll write out just the idea, and then try and do it in my head.”

The pages are filled with ideas that reminded Brecker of tactics used by different soloists. On one page in Book IV, there are several lines he’s noted as inspired by Woody Shaw, and others by Joe Henderson. These are short riffs, as the quote above suggests, Brecker used them as starting points for practice. He’d play the phrase in half steps up and down, then whole steps, then around the cycle of fifths, then in random sequence.

The first notebook, from his college days at Indiana University in 1967, shows how he was taught harmony in classes – and then how he took the basics and elaborated on them, as a practice challenge. He used those skills as he learned standard songs, applied them to his own compositions. The notebooks suggest a kind of generative learning model, a form of “basic training” that gave Brecker not so much a stockpile of licks as a system for creating ideas and inventing in the moment. He didn’t play by feel all the time; he practiced these devices religiously so that when he was in a playing situation, he had the tools to take an idea, anything bouncing around the room, and develop it from a seed to full flower.