...It's Not Just About the Epic

Thoughts on duration, deep listening and the current state of music.

For a while now, my Facebook feed has served up active threads, from musicians and non-musicians alike, expressing general concern about the current state of music. OK, “concern” is the wrong word; maybe “alarm” gets closer. These are not in any way coordinated, and they’re not wild rants. They’re written by people who clearly love music and are startled by what they perceive as its de-evolution. They’re worried about how banal and predictable a sizable chunk of it has become. How the stuff that “works” in pop is, by necessity, endlessly repetitive, lacking in harmonic content or variation.

One comment: “At a certain point music became high school basketball cheerleader chants.”

None of these observations are necessarily new, or unique to the present moment. The conditions they diagnose are not really even actionable, given that there’s clearly a large audience that likes music this way. Nothing the music lovers and practitioners of FB identified as concerns are even remotely problems for those listeners.

Are they problems for the evolution of music? And the audiences for music?

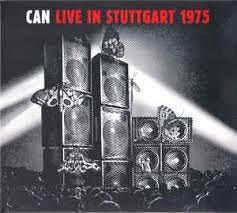

Here’s what would be a problem for these listeners: Asking them to devote ten or twenty minutes to a single piece of music, with nothing else going on. Earlier this week I wrote about Can’s Stuttgart 1975, which documents the group’s extended improvisational explorations on a single night. Each of the pieces has peak moments and deep lulls – knit together with interesting off-peak moments where new ideas get batted around, and tension builds almost imperceptibly.

There’s lots of music like that – it can be thrilling to witness a master improvisor like John Coltrane shape a single melodic idea into a sustained, multi-faceted array, a universe of ideas. As with Can, the thrill is not just embedded in the fireworks-erupting “reward” moments; it’s found by following the route the artists took, listening to the real-time searching, the development phase.

That takes a certain kind of ear. When the Facebook commenters lament contemporary music, they’re also lamenting what might be called “ear atrophy,” the absence of the will, the curiosity and/or the discipline necessary to engage music that doesn’t deliver its payload of fireworks within the first thirty seconds.

For several generations, standard public education in the U.S. has not included music history or appreciation in the required curriculum. That means it’s highly likely that generations of students have never followed a piece of music that lasts more than six minutes. They’ve not traced the path of a melody that twists and turns and doesn’t comfortingly repeat for 16 measures. Having grown up entirely on loops that last two or four measures, they might lack the processing ability to follow ideas in longer arcs, or recognize the variations of a theme.

Quincy Jones speaks often about this. In an interview I did with him years ago, he said he was growing worried about future generations of listeners. “Everything is organized around very small units [in pop]. Four measures again and again….While, of course, if you look at the history of music, the thematic ideas, the melodies, would last a lot longer than that.”

For me this longview is where the alarm bells start ringing.

Humankind struggled for centuries to gain proficiency to accomplish amazing things, developing languages, tools, systems of thought. And now here we are, with it all at our fingertips, and a chunk of the population expects the rewards of music delivered instantly. This group seems unable to follow a beautiful wandering melody as it winds through a ten minute symphonic work, or a jam from Miles Davis’ electric bands that bubbles along without fully coalescing into a “theme” for minutes.

Music people know the benefits, both psychological and physical, of unplugging for twenty minutes and engaging in deep uninterrupted listening. How do we evangelize about this experience to the uninitiated? Is it even possible anymore?

In an extraordinary New York Times interview about her HBO series Mare of Easttown the other day, actress Kate Winslet lamented some of the under-explored socio-cultural changes wrought by social media. “Everyone is constantly taking photographs of their food and photographing themselves with filters,” she observed, adding that she sees this behavior as a symptom of deeper issues – notably where people put their attention.

“In general, I would say I feel for this generation because I don’t see it stopping, I don’t see or feel it changing, and that just makes me sad because I hope they aren’t missing out on being present in real life.”

Music is one way of being present in real life. It happens over time, and time is exactly what it demands of listeners. For this playlist, I went for works of significant duration, but time wasn’t the only consideration: I looked for pieces that offered a kind of expansive, slow-motion drama: The tense climbs up difficult mountains, the majestic stillness at the peaks. And everything in between.

Why yes, we have a fancy digital suggestion box. Share your favorite Underloved/Overlooked records here: echolocatormusic@gmail.com.

Please consider subscribing (it’s free!). And…..please spread the word! (This only works via word of mouth!)

there's a lot here, Great Composer Anonymous! this topic becomes a "layers of the onion" thing the more I think about it.....thanks

I enjoy your writing. Glad to find you here.