Here’s a further thought on those protracted conversations between musical innovators – like the Rev. Gary Davis, discussed here last week – and those who pick up the influence and take it further: Sometimes the discussion gets interrupted. Or disappears.

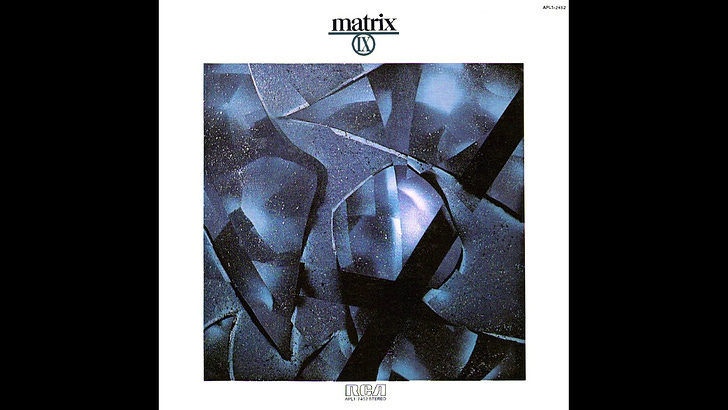

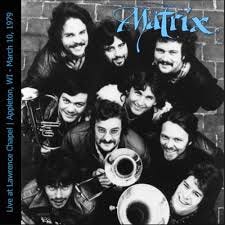

That seems to be what happened to Matrix (or, in its first incarnation, Matrix IX), a nine-piece fusion band from Appleton Wisconsin whose debut album was released independently in 1976 and picked up the next year by RCA.

This group’s marketing hook, if you could call it that, was its brass and winds front line; the composers, notably keyboardist John Harmon, were clearly influenced by the brassy jazz-tinged rock of Blood, Sweat and Tears, Chicago and the Electric Flag that erupted in the late 1960s. Following BS&T’s example, those acts delivered a bold, exuberant sound that became a regular presence on the pop charts for a few years, and inspired a wave of bands that refined it further – among them Chase (four trumpets!) and Tower of Power.

Matrix might have become part of that conversation had its forward-leaning if chattery fusion had arrived in, say, 1973. By ’76, BS&T was a blur of personnel changes, Chicago was sliding into easy listening with its 10th release, and the horns-up-front thing smelled like it belonged in a musty cruise-ship lounge serving sticky drinks and “live entertainment.”

The gentlemen from Wisconsin were evidently not troubled that they’d missed this particular trend train.

Matrix’ debut juxtaposes funk and rock grooves against elaborate orchestrational flourishes. Several pieces are built as suites – rolling through multiple themes, sudden tempo changes and loud-soft dynamic surges. These echo (and extend) devices commonly used in big band arrangements; by incorporating synthesizers and phaser/flanger-type effects into the voicings, Matrix conjured a fierce, enormous sound that could travel just about anywhere on the timeline. A Matrix epic might include a gorgeous rubato keyboard solo followed by a catcalling Basie shout chorus followed by an impressionistic flutes-and-brass interlude followed by a spry, tightly wound uptempo groove in the style of Return To Forever.

This band pulled that off, made those preposterous-on-paper transitions feel musically natural. While there’s some Broadway-fanfare bluster in the writing, the Matrix debut and two subsequent albums (Wizard and Tale of the Whale) for Warner Brothers showcase stunningly precise group execution and rousing (and often brief) solo excursions.

And, crucially, the band evolved. Not long after bassist Jaco Pastorius jolted the improvised music community with his evocative soloistic approach in the mid ‘70s (first in collaboration with Pat Metheny, then on his 1976 debut), the Matrix bassist Randy Tico embraced Pastorius’ instrument, the fretless electric bass, giving the group a new texture that became integral to its later records.

Just that sliver of a side conversation is interesting: Because Pastorius’ arrival is portrayed as a galvanic, era-defining moment in the history of bass, it’s easy to overlook the impact his sound had elsewhere, on composers like those in Matrix – and, to go a step further, songwriters like Joni Mitchell. These artists (and others) heard Jaco’s angelic, gracefully arcing long tones. Wanted some of that for their own work. And guided by nothing more than that sound, wrote it into being.

**

David Sanborn, the alto saxophonist whose list of electrifying cameo appearances includes that Pastorius debut, died yesterday. The many remembrances testify to his urgent and insistent sound as well as his impact as a demon of the 8-measure solo break — and, also, his canny instincts as a record-maker who knew just how much to challenge his (sizeable) pop-jazz audience.

There’s one record that’s a serious outlier in Sanborn’s catalog: 1991’s Another Hand, produced by Hal Willner and Marcus Miller and featuring guitarist Bill Frisell and drummer Jack DeJohnette. Sleek and spare and luxuriously shadowy, it’s an astonishment of nuance, an artifact from a time when stretches of near-silence on a record were welcome as part of the spell. The saxophonist mostly avoided this musical path over the course of his long career; listening today, that registers as something to lament.