In ways large and small, the music of the present is constantly engaged in conversation with the music of the past.

Recalling how he and Jerry Garcia obsessed over and analyzed the music of the Rev. Gary Davis, Bob Weir, the Grateful Dead guitarist and singer, described the blind Reverend this way: “He had a Bachian sense of music which transcended any common notion of a bluesman.”

There’s a timeline-blurring mouthful. In Davis’ fervent verses and unerring finger-picked guitar, Weir and many others – including Ry Cooder, Blind Boy Fuller, David Bromberg and Dave Van Ronk – heard not just the immediate genre geolocation (what historians call the Piedmont blues style) but the deep past, and the deeper past and, crucially, some glimpse of the future. Those artists (and many others) sought Davis out, sat with him to learn what they could of his methods. And then they went out and created original music. Sometimes that music contains clear evidence of Davis’ specific influence, embedded in a phrase or a chording trick. And sometimes it doesn’t. At all.

This chain of inspiration is an essential circuit on the great motherboard of music, part of the oxygen and the alchemy. Seizing maybe just a microsliver of inspiration, the artist tears off for points unknown. Even if the links in this particular artist’s chain are unclear, they exist as part of the larger conversation — one that continues out of time, across generations. It might go quiet for a while and then suddenly roar back.

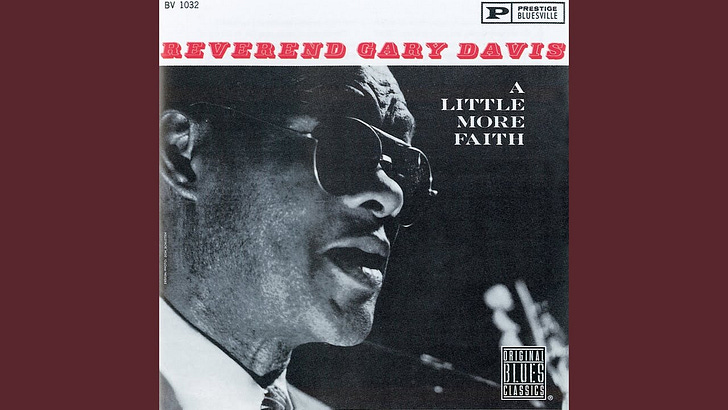

That’s what happened with the Rev. Gary Davis. Blind since he was a young boy, he recorded a set of plaintive spiritual songs in 1935; two years later, he became an ordained minister. He’d started out playing on streetcorners in his native South Carolina, and after that first recording, began doing the same thing in other towns on the East Coast. He became one of the “guitar evangelists” (others included Blind Joe Taggert and Blind Willie Johnson); in his travels, Davis encountered blues artists who incorporated elements of ragtime and the Piedmont blues style (among them the legends Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee), and over time those ideas filtered into his work.

According to biographer Ian Zack – whose 2015 book Say No To The Devil offers a comprehensive account of Davis’ difficult life – the guitarist and singer continued his street-level crusading after moving to Harlem in the 1940s, gradually incorporating (and then writing) classic blues songs to performances. The first recording from that period is the at once invigorating and harrowing Harlem Street Singer.

Davis was among those musicians who were rediscovered in the early 1960s during the folk and blues revival – during which young artists awakened to conversations that had been abandoned decades before involving long-forgotten troubadours, among them Mississippi John Hurt, Son House, Lightnin’ Hopkins and others.

Davis found himself suddenly in demand and in the spotlight – a curious state given that his music had not changed much at all. Perhaps because his finger-picked approach connected, somewhat, to folk and blues strumming styles, a number of rising stars sought him out; Cooder snagged lessons between Davis sets in Hollywood, others trekked to Harlem. The guitarist and educator Stefan Grossman, whose online site breaks down Davis’ unorthodox style, studied with Davis for three years.

Weir brought the evergreen “Samson and Delilah” to the Grateful Dead in the late ‘70s; it became a staple of the live shows beginning in 1978. The arrangement was based on Davis’ version – Weir studied with Davis over several years during tour stops in New York. He once described Davis’ approach as "stride piano playing adapted to guitar," an apt conceptual leap that underscores these improbable and endlessly fluid pathways of inspiration.

To create a bit of a mind map of “Samson and Delilah,” start with the 1927 recording by gospel-blues pioneer Blind Willie Johnson:

Then, for context, detour into a taste of ragtime – Davis was known for a thrill-ride version of Scott Joplin’s “Maple Leaf Rag.”

Then pay attention to Davis’ astoundingly precise approach on this 1964 version, recorded by Rudy Van Gelder on The Guitar and Banjo of Rev. Gary Davis:

And how about some Peter Paul and Mary? They did it, under the title “If I Had My Way,” this way….

Then drop into any live Grateful Dead version of the song. (For a deeper dive, check out the band’s intense treatment of Davis’ “Death Don’t Have No Mercy.”)

Of course, that transfixing performance is hardly any kind of definitive endpoint: here’s a 2010 recording by Robert Randolph and the Family Band.

And so on. It’s a safe bet that the majority of those who were thrilled and transported by the Grateful Dead doing “Samson and Delilah” had never heard of the Rev. Gary Davis, or any of the other antecedents. Doesn’t matter. The important thing is that those audiences were stirred by an approach, a mode of expression carried across decades – the same one that captivated Weir and Taj Mahal and Ry Cooder and so many others.

As Davis himself said at a David Bromberg performance in 1970: “I have no children, but I have sons.”

I'm grateful for this persuasive reminder of the importance of Rev. Gary Davis. My entry point to his work was the Grateful Dead's exploration of 'Death Don't Have No Mercy' on Live/Dead. Wonderful as that was, it was necessary to go to the source.

Thank you so much for this! I am a Rev Davis acolyte, too. Did you ever hear this punk homage to Gary? I think he would’ve loved it. https://youtu.be/GgATU599eDI?si=jVTZdWE8A1ifw4Ey