Every singer has a signature. Or ten.

Through repeat exposure, we listeners come to appreciate the particular constellations of tendencies that set one vocalist apart from another – maybe one uses a slight pause to highlight a line, another sneaks a quick in-breath to launch a phrase, another might shrug through a melody, letting the indifference become a magnet. The cues can be subtle, often ignorable. But they form a kind of aural “profile,” a bit like two-factor authentication, that aid or accelerate recognition.

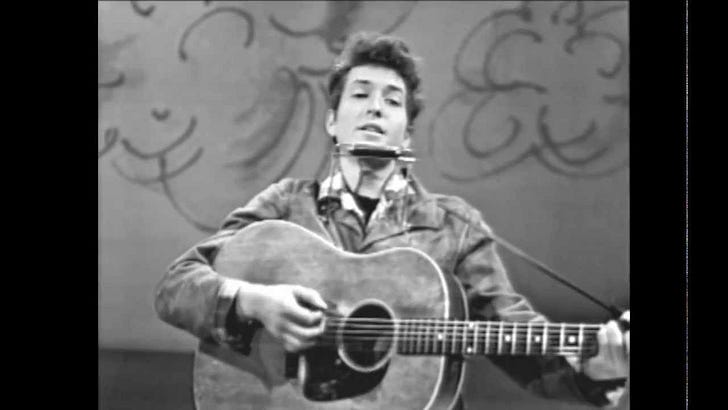

Bob Dylan, the frequently recorded singer and songwriter who is the subject of the new biopic A Complete Unknown, has a mansion-sized closet full of these. We know him from his wheeze. And the scowls he delivers with eyes narrowed. And the outsized, cartoonish way he lands on a word to activate all manner of emotional riptides, even when the evocation may be unrelated to the intent of the lyric. Celebrated simultaneously as a truth-teller and master of deception, Dylan borrowed some traits from bluesmen, some from revival preachers and some from crooners, treating the notion of “phrasing” as a junkyard patchwork. Uniquely American. Entirely his own.

Among these, though, there’s a thing he does that conveys Dylanness instantaneously: He sings out of tune. Often he’s well below the desired pitch, straining to climb toward some/any resolution amidst the thicket of a line gone awry. He plays fast and loose with equal temperament. He finds slots between half-steps that other singers would Auto-Tune into oblivion – and then leans into them to show that, oh yessir, he means it. For him, intonation is another tool in the kit of a bard and carnival showman, another expression used to underscore (or divebomb) the narrative.

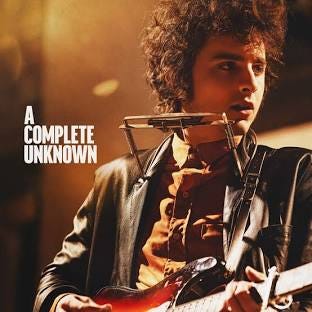

Many who’ve seen the film marvel that Timothee Chalamet genuinely sounds like Bob Dylan during the fertile period between 1961 and 1965, when he was evolving at a supersonic rate. For me, the astonishment of the performance isn’t that Chalamet manages such an unerring, almost digital imitation of Dylan at the microphone – that’s level one biopic stuff.

Far more interesting: In order to deepen this character study enough to make the music resonate, Chalamet absorbed and internalized the ways Dylan approaches and manipulates pitch. This actor didn’t just cop the outlines of the phrases or their most outsized gestures; he assimilated the traits (tricks?) that are central to Dylan’s identity as a singer. Chalamet understands what Dylan understands about the mechanics of landing the note – and as a result, he doesn’t have to constantly imitate the endlessly lampoonable Bob Dylanisms to evoke him. Instead, he conjures Dylan with shrugs and snarls and wounded-calf shouts resembling known Dylan maneuvers. Does it matter that Dylan himself quite possibly never used these gestures on any recorded version of any specific tune featured in the film? No. These devices are instantly identifiable as part of Dylan’s “signature.”

That’s an accomplishment. Had Chalamet merely gone verse-by-verse to retrace Dylan’s musical steps through “Like a Rolling Stone” and the other iconic songs, he’d just be throwing the bums a dime, and the Internet would be ablaze with outraged howls. (OK, forget that, it still is – see the cascading kerfuffles among critics and Dylanologists about historical accuracy and areas of focus.).

As Chalamet teeters on the precipice between consonance and dissonance, his performance speaks to how much nuance goes into an artist’s signature. He shows us a Dylan who is enchanted with the killer phrase and the extemporaneous rewrite, the genius line and the flying-leap elaboration that crams in more meaning than the words alone can hold. The early scenes portray Dylan as an uneasy performer, for whom the act of singing is a physical struggle with variable outcomes. Then, as his work is affirmed and his confidence grows, Dylan’s approach changes, grows more impulsive, visceral, irreverent, wild. Chalamet conveys this organically; his Dylan becomes alive to the expressive possibilities of implication and the visceral power of the wail. Chalamet doesn’t have to be a jukebox mimic, because he’s aiming higher and chasing the same physiological nerve center Dylan was chasing when he asked his most enduring question: How does it feel?