Who Will Stand Up For the Fading Diminuendo?

Thinking about classical music in a nuance-flattening cultural moment.

In the score of a symphonic piece, the indications for crescendo and diminuendo can seem slight. They look like the outline of a hairpin – getting wider for crescendo, narrowing to a point for diminuendo.

Encountering this dynamic marking, a trained musician understands what the score demands; to execute it, she scans the phrase and aligns her part with the entire group, making tiny adjustments in volume and intensity from beat to beat and measure to measure.

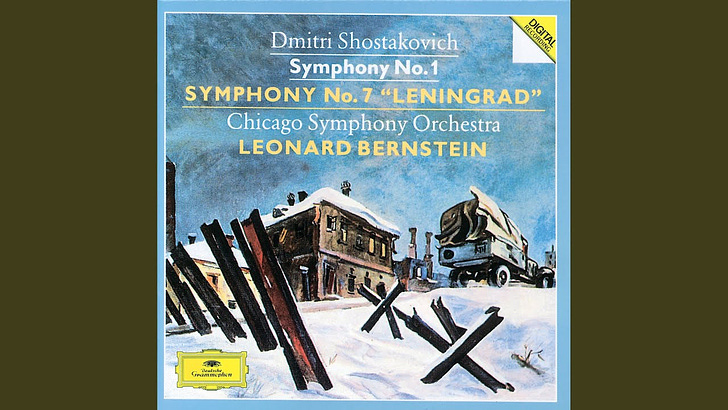

When 40 – or 60 or 100 – musicians all do this in the same way in real time, the result can be riveting. Overwhelming. Transportive. And oddly physical. The rapid crescendo sneaks up on the listener like a sudden clap of thunder. The slow crescendo suggests the solemn movement of infantry advancing in the distance – one of the more menacing crescendos in the orchestral repertoire is in the first movement of Shostakovich’s fabled “Leningrad” symphony, his 7th. In most versions it lasts around 12 minutes.

The markings might be small – they’re commonly printed below the notes on each part – but these shifts in volume and intensity are central to the evocative power of music. In his amazing Joys and Sorrows, legendary cellist Pablo Casals wrote extensively on this. "Diminuendo is the life of music," he asserted, explaining that a “prime function of the diminuendo is to bring the attention of the ear to the little notes.”

As Miles Davis and countless others showed, the little notes and the big spaces between them are the music.

[And let’s be real: These considerations of dynamics and other nuances are not limited to orchestral works, though it often seems that way. Here let’s briefly pause to lament the mezzo-mezzoness that’s descended over popular music in the digital era: Because so many records are made in cut/paste one-part-at-a-time fashion, the crescendo that results when humans play together – and not from some engineer riding a fader – is in danger of becoming an exotic thing, an arcane skill like spinning plates.]

The shadings, the slow builds and gentle dissipations, the brute-force eruptions – these aspects of art call on musicians to bring their humanity to the task of interpretation. It’s impossible to phone in or fake a crescendo, Casals argues. “The notes have to say something; [the musician] must give form, expression and interest.” And, crucially: “We must know how much to give, depending on what the music does.” Check the rapid crescendos and diminuendos in this Rossini overture:

This speaks to dynamic shading as an elusive, possibly unteachable skill: While most musicians know how to modulate volume, the rate of vibrato and other interpretative aspects, not all possess the instrumental control and sensitivity to mesh what they’re doing into the sonic motion that’s evolving around them. Not all can calibrate in ways that enhance the intensity of the passage – and, by extension, the performance as a whole.

This is the realm of music the AI bots will quite possibly never get – one (of many) elements of music that transcend notation. The musician doesn’t learn how to play a crescendo from a book or how-to video, a fact unwittingly underscored by this glib bit of text on the Master Class website: “The key to properly playing a crescendo is to gradually increase volume, rather than letting a dynamic shift happen all at once…This requires control of your instrument's dynamic range, so set aside practice time to focus on such control.”

Even those who do set aside practice time for this (!) find that the only real way to refine this nuanced set of skills is by being in a group and doing it. Over and over again.

This 2010 performance of Ravel’s “Bolero,” which is essentially one epic crescendo, illustrates how the act of incorporating dynamic changes involves sensitivity. It’s not a single set-and-forget decision, it’s hundreds of them occurring in real time, each a consequence of the previous, each aimed at some barely visible peak on the far horizon. This requires more than technical facility – it involves the ability to compromise, change course on the fly.

Oh that. We’re in a world where people (looking at you members of Congress) appear increasingly unwilling (or incapable of) cooperating on crucial life-or-death issues. Holding fast to a position is esteemed above flexibility.

In the current discourse, compromise is receding as a life skill. Apart from team sports, there are few examples of shared cooperative endeavor in our public life. The symphony orchestra, with its cresting waves of majestic chords and dazzling flamethrowing flourishes, is one of them. When an orchestra takes the stage, its assembled musicians work together. They put aside individual ideological and aesthetic differences in order to pursue larger group goals – to execute the score faithfully, and in so doing create moments of sublime grace and beauty.

Like this:

We think the orchestra is something that’ll endure forever. Hey, it’s older than the democratic system of governance of the United States! But like democracy, it can’t be taken for granted: To varying degrees, the financial health of most of the metropolitan orchestras in the U.S. depends on gift money from well-heeled philanthropists and grant organizations. The endowments might be robust today, but it doesn’t take a crystal ball to see challenges ahead: When the current class of classical music patrons die off, there’s a frighteningly small bench of young rich people waiting to replace them. (Don’t even get me started on the groupthink-infested grants aspect of this equation….).

For decades, these institutions have heeded – indeed, pandered to – the musical tastes of the check-writing patrons. That’s one explanation for “warhorse programming” – Beethoven and Brahms in abundance and much less representation of living composers or works created in the last fifty years. As veteran New York Times music critic Bernard Holland lamented in a 2023 piece: “Rejecting the new, symphony managements and the patrons who keep them in business have fallen back on the tried and true, repeated endlessly.”

That’s a recipe for failure. The orchestra administrators and boards are aware of this of course – they can still count! – and so have been ginning up all kinds of ways to captivate non-classical listeners. Last season the Philadelphia Orchestra offered a desperate, unintentionally laughable “crossover” program called “Brahms Vs. Radiohead.” Not only did it frame music in competitive terms – we might as well blame it for an Atlantic City tribute-band attraction this spring called Beatles Vs. Stones – the work of interpolation managed to do violence to the legacies of all involved. Including that of the orchestra itself.

This year the Philadelphia Orchestra tried a different tactic, booking Sting for an evening of his original hits set to orchestral accompaniment. The former Police frontman has made this type of performance a part of his schedule, commissioning arrangements that he can use in city after city. I didn’t go – the pricing was gouge-level, many tickets costing $800 and VIP packages as much as $1,500 for what was essentially a karaoke date. Were there crescendos?

This type of programming derives from the belief that on any given night, the repertoire is the lure – let’s go hear Sting sing “Every Breath You Take” with a really really big band! That’s certainly one way to draw listeners.

What orchestras are not selling, but certainly could, is something more primal/elemental: The experience of being in close proximity to that massive, telepathically unified group. Come be engulfed in sound. Come be rattled to your bones by the low brass. Come experience music at its most fragile and at its most frightening and lots of points on the spectrum in between.

The promise of a textural (dare we say paramusical?) experience is central to Icelandic band Sigur Ros’ current tour, which will return to the U.S. this fall. The group specializes in image-rich music that evokes states of yearning and grieving and inner-directed questing; for this tour, it performs with the New York-based Wordless Music Orchestra, which since 2006 has earned raves for its execution of new music works as well as the film scores of Radiohead’s Jonny Greenwood and others.

The orchestrations of Sigur Ros tunes are more elaborate than the typical long-tone pads and colors. As this performance from Toronto shows, the WMO, which is populated with graduates of Eastman, Juilliard and other top-level conservatories, nails the details of the band’s music, emphasizing dynamic contrasts and reinforcing moods as they unfold – evoking calm contemplation one minute, vast, fjordlike majesty the next.

“These are somewhat younger musicians,” says Ronen Givony, the founder of Wordless Music Orchestra. “They grew up listening to Radiohead and Sigur Ros and Bjork. They understand those musical languages – and at the same time they’re able to handle whatever left-field challenges might be in the score. And there are some.”

Maybe that’s the future – orchestras that are purpose-built to handle repertoire that scares off the more conservative ensembles. That doesn’t bode well for the once-mighty metropolitan orchestras in places like Chicago, New York, Los Angeles and elsewhere. Are they doomed if, in the not-too-distant future, they can’t fill seats by following the conventional wisdom of canonical pieces followed by more canonical pieces followed by wacky alienating experiments? And what happens if they need more evenings featuring classic rock heroes doing the “With Strings” move? Does anyone need the “Symphonic Pat Benatar Experience?”

The Wordless Music mission statement begins this way: “Wordless Music is devoted to the idea that the sound worlds of classical and contemporary instrumental music – in genres such as indie rock and electronic music – share more in common than conventional thinking might suggest.”

Musicians intuit this. They have for decades. Do the decision-makers sitting around the conference room table at the big orchestras? Stay tuned.

A great read, and very interesting on several levels. And Radiohead and Sigur Ros?! Bloody brilliant.