When the Breakthrough Hit Bigfoots Everything Else

The ballad of Steve Harley and Cockney Rebel

Sometimes the breakthrough hit gives new life to a rock band that’s toiling, mid-pack, in a crowded field.

And sometimes, as happened with the British part-prog part-glam Steve Harley and Cockney Rebel, the one big hit towers over the discography – becoming the media’s central reason to care about the band, often obscuring more significantly creative work.

The hit is “Make Me Smile (Come Up and See Me).” It erupted in 1975, reaching the top of the British charts and prompting an eternal wave of cover versions. (Among the more than 100 renditions is a famous live one by Duran Duran, captured in 1982 and issued as a B-side during the frenzy that followed that band’s own breakthrough hit “Hungry Like the Wolf.”)

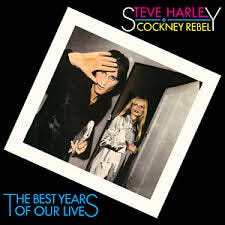

“Make Me Smile” is included on the third Cockney Rebel album The Best Years Of Our Lives. That’s the first release credited to the enduringly clunky “Steve Harley and Cockney Rebel,” after the musicians involved in the first two records abruptly quit over financial disputes. (Harley died after a battle with cancer in 2024.)

Harley styled himself as a classic audacious frontman character. He had a harsh, inelegant voice – an ideal conveyance for lyrics infused with regret and bitterness. He could be funny, in a bullying way; he had a knack for dismissive put-down lines. He could bray with the best of ‘em, but he was also a wry melodist, and a songwriter who wove elements of tango, cabaret and music theater into wild, energetic, structurally intricate songs. See “The Mad Mad Moonlight” and “It Wasn’t Me,” two of the surprisingly expansive tracks from Best Years. At least partially because of its big hit, that album was already properly memorialized with a 4-CD anthology set, but this week Chrysalis is bringing out a 2-CD plus DVD version that features a new stereo mix from the album’s co-producer Alan Parsons (!) and nine previously unheard demos and outtakes.

Until last week, I thought that since I knew The Best Years of Our Lives, I’d heard the consequential music made by Harley and Cockney Rebel. But something in a short UK piece about the new reissue sparked curiousity about the two records that preceeded the big hit. Turns out the first Cockney Rebel record, The Human Menagerie (1973), was engineered by Geoff Emerick – you know, of Beatles fame. Two of its tracks utilize a 50-piece orchestra. Suggesting that somebody in the big offices at EMI had an inkling about this unknown band and was ready to write checks that seem unfathomable today.

Harley and this iteration of Cockney Rebel were aiming at a uniquely ambitious rock sprawl – connecting the characterful eccentricities of Ziggy Stardust-era Bowie to wistful accordion and squealing saxophone serenades, building calm little Chopin miniatures into heaving rock epics. There’s a snarly song called “Mirror Freak” about Marc Bolan of T.Rex, and a crisp rocker, “Hideaway,” that shows Harley was able to ditch (or at least dial down) his pompous glam-rock striving to communicate in more direct ways when necessary. Tucked between the verses of many songs are colorful, unexpected instrumental passages: The band had no lead guitarist, emphasizing keyboards and the wily electric violin of Jean-Paul Crocker instead. And that’s before the orchestra got involved, on the syrup-slow “Sebastain” and a suitelike piece called “Death Trip” built on tense progressive-rock chord progressions.

The followup Psychomodo shows slightly more discipline. Harley’s trippy and neo-psychedelic wordplay (“Couch my disease in chintz-covered kisses” goes one incomprehensible gem) still runs freely, but at times it’s offset by darker, almost haunted imagery. At the same time, the song structures have a streamlined, almost conventional directness; on the highlight “Ritz” and a few others, the band supports Harley’s chatter with muscular, no-nonsense support. “Sling It” offers further proof of the rhythm section’s prowess: As Harley unspools surreal stream-of-consciousness poetry, the band pumps out the eternal three-chord magic of Bob Dylan’s “All Along the Watchtower.”

“Ritz” and “Sling It” exhibit the audacious renegade ambition that was circulating throughout rock at the time – throughout Bowie’s work, in the first Bruce Springsteen album, early Roxy Music and the lingering impact of the Velvet Underground. Gather all these up, add a shot of T. Rex and another of the New York Dolls and another of Kurt Weill and you’re in the general vicinity of Cockney Rebel.

In the liner notes of the 2012 compilation Cavaliers: An Anthology, Harley put it this way, talking about the songs he wrote for the band’s early efforts: "I remember where the songs came from. They came from a young man's dream, where the blending of musical literature and mad, formless imaginings, could hang out together at the same folk club and present him with an entire raison d'etre."

Always liked the ambition of the arrangements and Bowie-esque variety melodically. Just never dug his voice so much. Nice to hear it again… been awhile.