We Can't Rebuild Him

A scene from Oliver Nelson's last year on earth

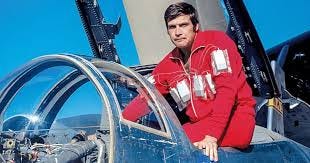

When the saxophonist and composer Oliver Nelson died in 1975 at the age of 43, he was experiencing a taste of certifiably rare Hollywood success: He’d composed (and arranged) the theme song for a runaway hit series, ABC-TV’s The Six Million Dollar Man.

Starring Lee Majors (above) as the bionically-enhanced title character, the series opened each week with Nelson’s spry, soaring, hipster-earworm theme, and a voiceover proclamation neatly explaining the series’ premise: “We can rebuild him; we have the technology.”

Nelson had been in Los Angeles since 1967; he’d written incidental music for film and television, contributing background music to Ironside, Columbo and other crime dramas as well as the memorably sultry soundscapes for Gato Barbieri’s saxophone in Last Tango in Paris. Known for intuiting the sonic ethos of a project, Nelson was a titan of the abstract atmosphere, a manipulator unseen but heard. And felt.

Throughout this period, Nelson continued to write and record jazz and jazz-adjacent albums. He did a series of records with international bands playing his charts: The 1970 In Tokyo, with Nobuo Hara and His Sharps & Flats, featured Nelson’s reveries on standards like “Autumn Leaves” and “Charade” and several breathtakingly gorgeous Nelson solos on soprano saxophone; Swiss Suite featured Nelson’s all-star crew (Charles Tolliver on trumpet!, Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson and Gato Barbieri on saxophone!) playing a 26-minute whirlwind suite); the forgettable In London with Oily Rags paired the saxophonist with a smaller group featuring four trumpets and two guitars.

And that’s not all: Nelson continued working at an impressive clip as an arranger for hire, contributing expansive, carefully voiced accompaniments on albums by Diana Ross, Leon Thomas and Doc Severinsen among many others.

Arranging is time-intensive work — and was considerably more so in 1975, before the advent of computer-aided production and notation software. You can’t help but wonder: How did Nelson manage the demands of multiple projects that were no doubt on simultaneous schedules, while creating incidental music for other hit shows and doing album projects?

Like many prolific composers, Nelson did some repurposing. “Three Seconds,” from his Screamin’ The Blues (1960) is threaded into the score of a Six Million Dollar Man episode; “Baja Bossa,” which Nelson quoted multiple times on the show, was re-recorded for his jazz-rock exploration Skull Session (1975). Some of those international big band albums contain modestly reworked tunes from earlier Nelson landmarks, including some from the arranger’s towering achievement — Blues and the Abstract Truth (1961).

Nelson might have been expected to cut a few corners; several obituaries mention that he spent the last few years of his life in a state of perpetual deadline-driven overwork. Still, when the virtuoso organist (and astute observer of pop culture trends) Richard “Groove” Holmes asked Nelson to collaborate on a new treatment of The Six Million Dollar Man title piece, Nelson rose to the challenge. He didn’t reheat the TV version, instead crafting a spry fantasia that expands the theme with splashy brass dissonances and darting, fast-moving, newly written counterlines framing Holmes’ solos.

Scoring with Holmes’ irreverent style and the exactitude of LA session musicians in mind, Nelson establishes a chipper uptempo pulse, and develops it with all the coloristic tools at his disposal (check the low trombone pads in the solo section). His mission is to frame the instant-on Holmes organ fireworks; he does this with crisp ensemble writing, and dashes of chase-scene camp that are not quite Batman — but not Kojak noir either.

The grooves percolate naturally, in the open-ended all-day simmer characteristic of jazz-rock fusion of the period. Some tracks, like “Disc-o-Mite,” dwell in a hypnotic conga-anchored Afro-Cuban rhythm not far from those on Ray Barretto records of the early ‘70s. Others are more overtly aimed at soul jazz (“125th Street & 7th Avenue,” which is made bouyant by an relentlessly popping Chuck Rainey bassline).

This album doesn’t turn up on many shortlists of essential Holmes recordings. But it has more than a few great performances, and is notable for the way Rainey and drummer Jim Gordon synchronize and sway. (Gordon’s not on the title track; the drummer on that is the delightfully understated Shelly Manne.)

And beyond that, the album offers another reminder of the under-documented creativity of Oliver Nelson. We encounter him here at a moment when he could be savoring hard-earned success, but instead he’s doing work, and relatively anonymous work at that: Helping Holmes make an altogether typical (and possibly cynical) attempt at crossover success.

Except Nelson doesn’t let it sound at all typical. These days technology might be able to rebuild the physical body, but it can’t install a chip that has the desire to create, or to transform or recontextualize. That creativity is innate. You have it, or you don’t.

Excellent piece on Nelson's work ethic and craft. That detail about him reworking the Six Million Dollar Man theme for Holmes instead of recycling the TV version really captures something important about artistic intergity. The contrast between spry arrangements and deadline pressure says alot about how top-tier musicians operate even under constraints. Nelson's refusal to cut corners in what could've been throwaway work is inspiring.

Great essay, Tom! Always loved Oliver Nelson. Thanks for the Groove Holmes stuff.