There’s a guy named Airton Leonardo who posts on Instagram under the_most_underrated_albums. You probably know him already if you’re into Brazilian music – he has an incredible collection of vinyl encompassing samba, bossa nova, MPB and all of the modern styles; his feed offers curated lists, accompanied by visuals of album covers, designed to celebrate and contextualize works he believes are essential to the evolution of Brazilian music.

Last week he posted this cover:

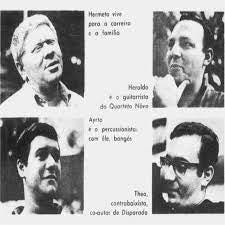

That’s the masterful, singular album from Quarteto Novo, released in 1967 on Odeon, featuring multi-instrumentalists Hermeto Pascoal and Herald do Monte, percussionist Airto Moreira, bassist/guitarist Theo de Barros. Don’t bother searching for it on Spotify: When you do, up comes a jank 2023 album called Bossa Sensual Frutis credited to Rachelle Spring, Quarteto Novo and Dominguinhos, the late accordionist from Pernambouco. Search another way, and Spotify serves up a bland Brazilian cover band that has zero connection to the above title except the name. File this one under More Reasons To Mistrust Spotify. (While we’re at it: Cross reference under “What Has To Happen for EMI To Properly Reissue This Landmark?”)

The real Quarteto Novo came along after the bossa nova craze, and before jazz fusion became ubiquitous around the globe. Its intricate, suite-like compositions stand apart from most everything else happening in Brazil at the time. These pieces are disarmingly open, defined by a chamber-music austerity. It’s art music with expansive, bebop influenced harmony that’s built from a foundation of baiao and other dance rhythms from the Brazilian Northeast. (The group came together in Sao Paulo after being hired by singer/songwriter Geraldo Vandré as his backing band; they enliven Vandre’s 1968 LP Canto Geral.)

There is so much to say about the Quarteto Novo record. Yet most of what’s significant can be traced to a single trait: An implied, shared sense of time. Drop in just about anywhere on any track, and the first thing you notice is that regardless of who’s playing what, all four musicians agree on the flyspeck permutations of the time. Down to every last partial. Nobody is relying on Airto’s percussion – hand percussion mostly – to define the pulse. The pieces, most written by Vandre, have grand-pause moments and unexpected detours into rubato. Some exist in a state of constant transition – in the space of just a few measures, “Algodoa” travels from a strange haunted-mansion blues into crisp uptempo bossa nova into a scurrying classical etude figure into a pulsating one-chord drone that provides the backdrop for a thoughtful too-short guitar solo.

Moving between each of these distinct “events” tests a group’s ability to phrase together. These four approach the task with telepathic grace, creating music that unfolds like breath – unerring, gorgeously lyrical, unified without becoming mechanistic. The record stands as a vivid illustration of implied time – a state of performance in which the musicians align with the pulse without needing it to be explicitly hammered out. Time becomes a magical agreement, silently upheld and reinforced from one downbeat to the next.

This isn’t exactly some exotic thing – symphony orchestras do it routinely. It’s much (much!) less common in contemporary pop and R&B, where the clocklike steadiness of a drum pattern provides unifying organization, the backbone of the grid.

The lone work by Quarteto Novo was revered in its time, and would be so again if it were accessible to the streaming public. Because it represents a way of orienting to rhythm that, far from being old-world arcane, is actually performance practice for the ages. It’s like porting into an opulent, under-explored galaxy of rhythm. A realm of layers and implications and spacious undelineated downbeats that operates on a different frequency. And suggests the types of possibilities that get instantly zeroed out when time is experienced digitally. Drop the needle anywhere on the record. You’ll hear it instantly.

Why yes, we have a fancy digital suggestion box -/ share thoughts on underloved & overlooked records here: echolocatormusic@gmail.com.

CDs available on Discogs for relatively reasonable prices, LPs of course very expensive. Someone at EMI should get it together and post it on the streamers. Unless there are legal reasons for keeping it off, how hard can it be?

Thanks for the tip - I need to dig in to this!