Don’t Tell A Soul

The Replacements

Released 1989 (reworked on Dead Man’s Pop, 2019)

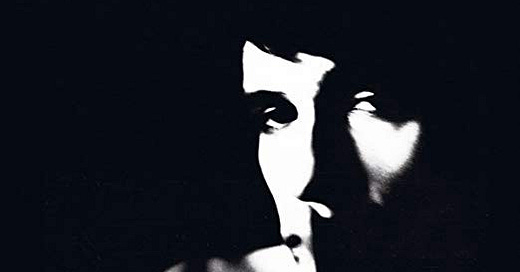

The noir glamour shots on the cover. The reverby Roy Orbison ring around the vocals. The high-sheen singles. For longtime fans of the Replacements, there was always something a touch too glossy about Don’t Tell A Soul, the 1989 album that became the band’s almost-kinda commercial breakthrough.

Those who caught the band live during this era remember something else: Sweat-soaked versions of low-key pop masterworks, freshly wounded songs that balanced snarl against sweetness. With a dark-hearted edge, almost veering into the sinister. These didn’t seduce on tiptoe; instead, like many Replacements battle cries, they punched into your consciousness one sticky chorus at a time.

On the album, the songs didn’t carry that same feisty wallop. They came across as pop creations, sculpted and preened, designed to charm at a distance. And almost masking the essence of the Replacements in the process.

At the time, there were whispers that some genius, either someone at the label or corporate rock whiz-kid engineer Chris Lord-Alge, got involved and gentrified things, disregarding the wishes of the band. Songs appeared in a sequence that was not the one made by the band. Extra sugar was added in post production. In some cases even the tempos were changed. The album became an indie-band’s symbolic nightmare, an artistic compromise that worked enough commercially to prove the suits right.

This being rock in the era when bands knew better than to put much faith in such illusory concepts as career, there is (naturally) a wrinkle. Before the meddling was finalized, singer/songwriter Paul Westerberg and producer/mixer Matt Wallace spirited a set of band-approved masters from where they’d been working, a mixing room at Paisley Park. Like good punk rockers, they tucked them away for safekeeping.

That version has been recently unearthed and remixed by the original team. It forms the backbone of Dead Man’s Pop, a 4-disc boxed set that restores “Aching To Be” and other astonishingly durable Replacements odes to the coarser, more ingratiatingly scruffy state the creators intended in the first place.

As a work of industry intrigue and score-settling, Dead Man’s Pop is a curious triumph, a satisfying revenge tale about artists taking control of the story they set out to tell in the first place.

More significantly, it shows how central the mix can be to the listener’s perception of a work: When rendered in less fabulous form, the exact same vocal performances give off a faint but unmistakable air of desperation. With the production stripped away, Westerberg’s couplets sometimes have acid-bath impact. Music that sounded distantly wistful on Don’t Tell becomes bitter and caustic and of immediate life-or-death importance on Dead Man’s Pop. The tone Westerberg used to share his sad-boy ball-of-confusion tales winds up saturating the tone of the tracks as a whole.

Much more than the usual “sonic upgrade,” the box restores the original Replacements vision, that intangible restless twitch that made these songs so tantalizing. It shows songs being born (the demo “Portland” was an early home for the hook from “Talent Show”) and lyrics being tested (the demo version of “We’ll Inherit the Earth” comes across as eerily prescient today). It includes a few goofing-around outtakes, a careening, sometimes out-of-control live show from the period — and the fruits of a deliriously loose session with Tom Waits, who slides gamely into the role of Westerberg’s wayward cousin on the slinky “I Can Help.”

The band-approved mixes provide a new lens through which to savor Paul Westerberg: As a shambolic songwriting genius who understood that the withering couplets had to be delivered a certain way, with a slight arch of a disbelieving eyebrow, to be impactful. The vocals on Don’t Tell are beautiful, but in a pulled-punch way that occasionally blunts the precision of the sentiment. The Dead Man’s versions of the same performances are more visceral, alive to multiple meanings and side-eye subtexts.

All by itself, this de-gooped lead vocal winds up expanding the songs: It renders character studies like “Achin’ To Be” and existential thought experiments like “I’ll Be You” as rivetingly immediate creations. They’re brainy songs but they don’t sound that way. They’re songs with meanings and layers of implication running beneath the killer hooks; songs you might know by heart but never fully understand.

That’s one way to measure a work: Does it intrigue on repeat encounters? Does it reveal some new dimension or angle over time? The songs Westerberg wrote for Don’t Tell A Soul certainly had that quality when they were first released thirty (!) years ago. Incredibly, they exhibit even more of that now.