The Time-Flattening Brilliance of Os Tincoas

The recently unearthed final record from an arresting vocal trio

The dude was a record store trickster. Wise and cagey, with an unruly beard. He knew what he had and delighted in telling customers that no, sorry, the prize gems in that particular bin were not for sale. His shop was a block off the ancient square known as the Pelourinho in Salvador do Bahia, where the old men sit around a table and drink beer and play incredibly spirited acoustic samba in the afternoons. Pelourinho translates roughly as “whipping post;” during the era of the slave trade, this was the intake center.

I was the only customer. He knew I was American right away (it was 2014, possibly before iPhone worldwide ubiquity), and in rudimentary English that was way better than my Portuguese, asked if he could help me find anything. Most of the records on the wall had some relationship to Bahia, so I asked him to recommend a few favorites. He bent down behind the counter and brought up a stack. As he did, he warned me that he had no copies of any of these to sell; the best I could do was take photos. And good luck searching.

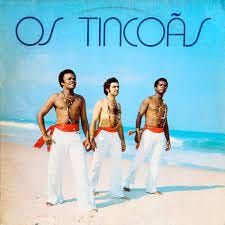

And then he fired up the turntable and began what seemed like his standard routine for tourists: He’d flip to an album and see if I recognized it. If not, he’d put it on just long enough for a taste. He started with the established names, Dorival Caymmi, Caetano Veloso and the rock-era firebrand Raul Seixas. Those I knew. Then came others I didn’t – sambistas and ancient bolero singers and a 1973 record from a trio called Os Tincoas. The cover, below, features three shirtless men in white pants walking on a beach.

Somehow I missed taking a photo of this one, much to my longterm regret. The snippet of sound stayed with me, however – the voices sliding between unison and reverent, prayerful harmony, the handmade groove just sauntering along, powered by woodblocks and congas. You know how a fleeting and partially remembered thing, be it an idea or a piece of music, can lurk in the brain, haunting and chiding you for not taking better notes? Staying there like stuck energy, for years?

That was Os Tincoas for me, until a few weeks ago when the New York Times ran this excellent article about Os Tincoas’ percussionist and singer Mateus Aleluia, and a long-unreleased work recorded in the early ‘80s called Canto Coral Afrobrasileiro. Before I heard that I went to see if the 1973 record, one of several self-titled LPs, was the music I remembered, and discovered that my record store guide had played side 1 track 1, “Deixa A Gira Gira.” It is even better at full length (link above), a sublime way to spend three minutes and 25 seconds.

That led me to a journey through the small but disarmingly potent Os Tincoas discography. The trio started out in the pre-rock creamed-corn pop of the early ‘60s, offering earnest readings of boleros enlivened with plush doo-wop harmonies. Meu Ultimo Bolero (1961) captures this period; had the trio continued in this lane, it would have been compared with the entertaining doo-wop-loving Cuban group Los Zafiros.

Os Tincoas disappeared, and then, after a long hiatus, reconvened to explore music that reflected the post-slavery fusions of African and Brazilian culture – drawing on Yoruba chants and samba pulses and the call and response exchanges that are part of the Afro-Brazilian Candomble religion. This blend changes from song to song: Sometimes the crisp recurring phrases of Candomble ritual are the focus, and at other times the calming, joy-affirming vocal harmonies surge to the forefront.

Everything Os Tincoas recorded after that 1973 title is essential listening. Among its most enduring works is a song called “Cordeiro de Nana,” recorded in 1977, that speaks to the psychological stress inflicted on enslaved people, and the ways the spirit world – Nana is regarded as the grandmother of the orishas – inspired strength and resilience. One verse begins “My woe began with the slavery into which I was forced/I cried, the severe pain of humiliation/But I prevailed, for in my heart I carried Nana.”

The group’s nuanced, multi-faceted laments and songs of perseverance never resulted in what we’d call breakthrough commercial success. Still, those harmonies got under people’s skin, had lingering impact on musicians and listeners; in the Times article, the singer Margareth Menezes, currently serving as the Brazilian minister of culture, recalled hearing them as a child. She credits the group with representing “the African roots of Brazilian music.”

It turns out Mateus Aleluia was committed to this as not just history, but a facet of Brazilian identity: The Times story explains that during a 1983 tour in Angola, Aleluia and a bandmate decided to stay, essentially dissolving the group. Aleluia spent 20 years there, teaching and learning about the Africa-Brazil diaspora from the West African side.

Canto Coral Afrobrazileiro, which was recorded in the early ‘80s, was sparked by a radio DJ named Adelzon Alves. It situates the core Os Tincoas vocals-forward sound in a more elaborate setting: on most pieces, the trio is accompanied by a large choir, the Coral dos Correios e Telegrafos do Rio de Janeiro. This swells the trio’s compact 3-part harmony to near-symphonic scope, and it propels the group’s originals – which here are entreaties to such orishas as Lemanja (or Yemanja, the goddess of the oceans) and Obeluae (the god of earth, fire and death) – into simultaneously more somber and more ecstatic realms. These are resonances as much as songs. They connect rolling 6/8 African pulses with samba percussion, and then with the solemn entreaties repeated in church. As they unfold, these moods grow into disarmingly stirring dialogs — between the unquiet, imploring ancient and the chaotic, perpetually distracted present.

Gorgeous record.

A revelation! Just beautiful, thank you for moving the discovery down the line