The Place Where "Artist Development" Thrived

On the passing of Mo Ostin and the impact of Warner Brothers Records

Disclaimer #1: The ideas below are not original to me. They have been voiced many times over the last week by those who were lucky enough to be involved in the music business during the album era.

Disclaimer #2: It all bears repeating.

Music people are still mourning Mo Ostin, the legendary Warner Brothers record executive who died last week at age 95. Reading the remembrances, I couldn’t shake one lamentable thought: Ostin had the misfortune of outliving his approach to the art of record-making. Which vanished a long time ago. Possibly decades ago. He had to witness an epic changing of the guard -- as the geniuses and misfits and rebels who’d helped make Warner Bros. into a legendarily dynamic place were gradually displaced by “artists” only a beancounter could love.

And the entire ecosystem of music is poorer for it.

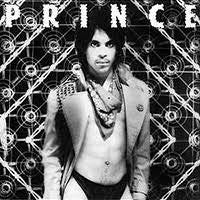

Not simply because popular culture requires a degree of boundary-pushing weirdness, but because Ostin and his team – musicians and producers like Lenny Waronker, Russ Titelman and Ted Templeman – demonstrated over and over again that there was value – even market value – in the unconventional. These people did not regard record sales as the only metric of success. They wanted hits, sure, but they held an abiding faith in the galvanizing power of originality. They made Warner Bros. into the rare hitmaking machine that had room on the roster for zany roots musicians with eclectic tastes (Ry Cooder) and mystic poets (Van Morrison, who did his best work at Warner Bros.), and totally unproven unknowns (the multi-instrumentalist Prince Rogers Nelson, who was signed at age 19 to a three-album (!) contract that gave him full creative control of his output).

Let’s pause and think about that, as Prince’s early manager Owen Husney did in a comment last week on Bob Lefsetz’ insightful music business Lefsetz Letter. “When I told them that we wanted three albums firm when we signed him, Mo gave the green light - no other label would have done that. When I told them that an 18 yr old kid from Minneapolis, who had never recorded an album, was going to also produce his first album and play all the instruments - he was given the green light. No label at the time would have done that. When Prince told WB not to pigeon-hole him as an R&B artist because he wanted to make music for all people - they believed in his vision. No other label at the time would have done that. But Mo was at the helm at WB, and he created that environment.”

Prince’s contract was a gamble for the label; his first album For You (1978) didn’t attract the expected press attention and its biggest single, “Soft and Wet,” peaked at 92 on the Billboard Hot 100. In today’s environment that would – and often does – spell “Game Over.” There was no evident panic at Warner Bros., however. And we know how that turned out: An artist who began as a smart student of R&B styles became, within those first few records, a thrillingly individual once-in-a-century voice who fulfilled his intention to create music for all people. Make no mistake: He did the work to evolve that way. But Ostin and the label team deserve credit for creating the conditions for that growth. For the key cultivation stage.

There are variations on this story involving literally hundreds of artists – Neil Young, Randy Newman, Fleetwood Mac, Emmylou Harris, Madonna. The details vary but they share a common theme: The label’s emphasis on artistry and the once-common/now-quaint term “artist development,” its patience and willingness to think long-term.

Ostin was hired away from Verve by Frank Sinatra to run Reprise Records in 1960; the label’s mission was, simply, to empower artists. After Reprise was bought by Warner Brothers in 1963, Ostin ascended rapidly in the combined company. That was partly a result of his temperament: He was low-key and humble, a calm figure in a realm where audaciousness was prized; his approach contrasted sharply with the moves of the musically indifferent, ruthlessly capitalistic music-business executives who dominated early rock and roll. Ostin understood the cultural shifts of the late ‘60s and the ways those changes were finding expression in music. He signed exploration-minded rockers and deeply introspective songwriters and artists who challenged all sorts of status quos.

And after the contracts were signed, Ostin got out of the way.

This may be his most salient contribution. Ostin understood the erratic vagaries of art-making – the time it could take to craft a song, the artist’s need to experiment in the course of recording an album. Where most labels expected instant results, he and his team encouraged artists to think in more expansive ways about their work. To play and explore. To chase ideas, even ones that might not pan out. The Warner team cultivated the big swing and the long reach: Within six years of signing to Warner Bros. as a solo artist, Paul Simon created the wildly ambitious Graceland, which weaves together elements of African music, doo-wop and Southern roots styles in ways never attempted before.

It's difficult to precisely map the total the impact of the Warner approach on the history of popular music. Proof of its wisdom (and enduring value) is most evident in the thousands of WB recordings themselves, not in the Wiki pages with chart positions or the books describing this unusual corporate culture.

Warner Bros. under Mo Ostin showed that it was possible to operate as a conglomerate while cultivating art with the zeal of a boutique operation. It challenged listeners with works that defied genre classification and transcended bottom line thinking. Not all of these were chart-toppers. They didn’t have to be.

I know you did Skip! Such a legacy!!!

I seriously always wanted to meet Joe and Mo...the guys who really made it all happen