The Kids Are Alright Department

Following a tattered twisted thread through Clarence Ashley, Taylor Swift, Noah Faulkner, Kate Bush and Doc Watson

The cry of the besieged music critic rattled far and wide through the social media ideaplex. It told of a woeful strain of predictability in the music, and the effects that can have on those whose job it is to parse the exploits and artistic utterances of the big stars. The artist in question here was Taylor Swift (of course!); the critic, Chris Richards of the Washington Post, served up an unusually personal plea in the closing stanza of his review of Swift’s new The Tortured Poets Department.

"…I would argue that pop music is for everyone. You’re here, I’m here, I’m writing, you’re reading, we’re in this listening life together, and it’s probably just fine to wish that the most widely circulated music of our lifetimes might be more imaginative and less self-obsessed. We’re long overdue for a Swift album that feels even a little bit curious about the world she rules."

First thought: We’re not overdue for anything. The artist – any artist – is at liberty to follow the muse wherever it goes. Sometimes that leads to incomprehensibly beautiful expression. Sometimes we find ourselves in a cul-de-sac of indulgent self-reflection. As commentator, Richards is expected to describe and contextualize the work for his readers; the minute a critic starts wishing and hoping and prescribing in print for an artist to do anything, it’s probably time for that writer to seek opportunity in the Neglected and Understaffed A&R Department.

Second thought/full disclosure: I have not yet listened to the new Swift. (Is this malpractice? File a complaint with the Disenfrancised Critics Department.)

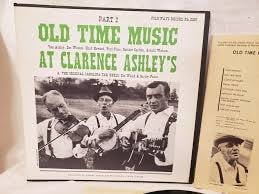

I’m late on Swift because I’ve been knee-deep in the boggy rustic majesty of Clarence Ashley, the singer, songwriter and clawhammer-style banjo virtuoso whose Wikipedia page identifies him in the category of “old time musicians.”

Ashley was born in the fertile musical territory of Bristol, Tennessee. He played medicine shows as a young man, and recorded for Columbia starting in 1929. He had a few minor “hits” – “The Cookoo Bird and “The House Carpenter” – then worked a bit as a comedian with the Stanley Brothers before retiring from regional touring in 1943. To support himself and his family, he founded a trucking company that hauled coal and furniture.

Ashley’s Depression-era work was included in Harry Smith’s landmark 1952 Anthology of American Folk Music. That triggered a rediscovery, which led to a scattered few spirit-rousing recordings, including the amazing Old Time Music at Clarence Ashley’s. Alternately exuberant and death-haunted, this live set was produced by mandolinist and Smithsonian folk-arts curator Ralph Rinzler. It’s notable to history as the very first recordings featuring guitarist Doc Watson. (The most comprehensive release appeared in 1994 as The Original Folkways Recordings of Doc Watson and Clarence Ashley, 1960-1962; it’s got 20 tracks not offered on the original.)

I was reminded about Ashley by another piece of music journalism, this one by Stephen Deusner that ran in the New York Times on April 1. It tells the story of young Noah Faulkner, age 16, who has earned a devoted YouTube following with dexterous and high-energy instrumental versions of pop hits of the ‘80s and ‘90s. Here’s the waltz that gave me double-take-face:

Faulkner is on the autism spectrum. He and his brother, bassist Nate (age 13), record their videos at home, with a large Texas flag in the background and a dog, the adorable and usually panting Kara, sitting in the foreground. The unpretentious look and bracingly earnest sounds (check the rendition of Joy Division’s “Love Will Tear Us Apart” below) have led to a bunch of press coverage already – and the group snagged more after performing at the request of the Black Keys at this year’s South By Southwest festival.

Tellingly though, the very first detail in the Times piece is not about the channel’s subscriber count (1.86K!) or the astonishment that Noah Faulkner has had exactly one lesson on his unforgiving and difficult-to-master instrument – from Lloyd Maines, the legendary Texas musician and producer.

Instead, it’s about one of Faulkner’s recent obsessions: Clarence Ashley, whose crisp, deftly articulated music conjures images for him. He says Ashley’s music ““feels very spooky, and I imagine it’s like an abandoned place somewhere.”

Here’s a kid who owns a Black Sabbath shirt talking poetically about what, to most living souls, is ancient history. Savor that, and also this: In the course of exploring the rich history of his chosen instrument, the pedal steel guitar, Faulkner somehow crossed paths with a wily banjo player and singer from the strange freewheeling renegade roads of the distant past.

Faulkner likely found Ashley on his own, and when he did, he dove right into that brackish water. And then stayed there long enough to absorb the precision of the phrasing, the keening sweetness of the melodies. And then he transported them into his own innate expression. Which, of course, is exactly what Charlie Parker did when he encountered Lester Young. And so it goes across decades, a discourse wavelength that happens in every style of music or tiny forgotten subgenre that’s ever been left for dead on the side of the road in the march of “progress.”

To borrow the central relevant phrase from Richards’ Swift review: Faulkner is clearly curious about the music world he inhabits right now, and the music worlds that came before. At an age when some of his peers obsess over the outfit they’ll wear for their next TikTok opus, Faulkner is engaged in the eternal work of understanding – and, where possible, reconciling with – the alluring, sometimes repellent, always inescapable past. He’s at the start of his journey, and yet, through the gorgeous sloping contours of his deep and gingerly embellished melodies, he’s already participating. He’s part of the chain of mulching and flowering and seizing and rejiggering on the way to contributing something new.

Just that much is encouraging, on a “the kids are alright” level. And it’s reason enough to keep an eye on the evolution of Pedal Steel Noah: If he’s listening to Ashley now, what’s he going to sound like when he runs into Miles Davis?

So good, Tom. As for the WaPo critic, it’s not that I dislike his criticism so much as it is so easy to just ignore it. My essentials remain Ted Gioia, Geoffrey Himes, Robert Christgau, Robert Bentley, Nick Dedina, and you Tom Moon.

I used to follow Greil Marcus closely … but now mainly just read his responses in his Ask Greil postings on his Substack. When he responds, he is in a much more positive mood than when he just writes his regular offering.

Fantastic piece Tom, I loved it, thank you!!