The set opens with a march. Elvin Jones is at the kit in a little-known New York club called Pookie’s Pub, rattling out the first chorus of “Keiko’s Birthday March” alone. It’s not some hipster-stylized jazz march – more like a starchy, buttoned-up military march, gaining steam with each precision press roll.

The band enters but Jones remains in formation, countering the theme with more drum-line chops. And then Joe Farrell dives into what becomes a marathon tenor solo, and, at last and instantly, the vibe changes. We get the propulsive ride cymbal, and the searching, cresting swing feel that Elvin Jones developed and wholly owned. The stunning transformation happens in just eight measures – and that’s all the time Jones needs to clear out the residue of the march and create the open-road conditions for modal exploration.

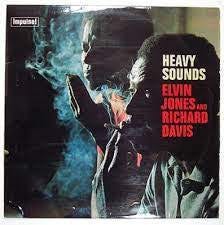

Recorded over several nights in July, 1967, the previously unreleased Revival: Live at Pookie’s Pub provides new perspective on the world of Elvin Jones after 1966, when he left the enormously influential band led by saxophonist John Coltrane. The drummer was still in high demand for studio dates; he began a weekly residency at Pookie’s to develop original music for his own projects, and within a year began recording a series of albums for Blue Note, including the remarkably ageless Poly-Currents (1969). (Contemporaneously, Jones and bassist Richard Davis recorded one of the unfairly overlooked gems of the era for Impulse – the aptly named Heavy Sounds, discussed previously on Echo Locator here.)

The Pookie’s Pub recording was brought to Blue Note by jazz detective Zev Feldman, whose work in recent years has filled in significant gaps in the recorded history. Jones is a perfect candidate for deeper scrutiny: By 1967, he’d not only made A Love Supreme and other classic recordings with the Coltrane Quartet, but in a foundational way shaped the aesthetic of progressive improvisation – via works by Wayne Shorter (Speak No Evil), McCoy Tyner (The Real McCoy), Joe Henderson (Inner Urge). To gain fuller understanding of the impact of a figure like Elvin Jones, it helps to look beyond those totemic peak works, and check out what he was doing in less rarified air. On an “ordinary” night. At places like Pookie’s.

Coltrane died on July 17 1967; Revival was recorded two weeks later, so way too soon for any musician to be thinking in terms of a “post-Coltrane” world. But post-Coltrane this is. It finds Jones and his rhythm section – pianist Billy Greene and bassist Wilbur Little, with Larry Young guesting on piano for a thrilling “Gingerbread Boy” – transforming highly technical individual solo passages into thrashing collective outbursts.

Farrell adheres to the harmonic paths of the originals and standards like “Softly As In a Morning Sunrise,” dipping in and out of Coltrane discipleship from phrase to overstuffed phrase. He seems to relish the incessant challenge, mastered by Coltrane, of developing cogent melodic ideas while navigating Elvin Jones’ choppy shapeshifting rhythmic terrain. Coltrane had years of experience working within the Jones maelstrom, which he thrived on: In Frank Kofsky’s book Black Nationalism and the Revolution in Music, Coltrane is quoted as saying “There's always got to be somebody with a lot of power. In the old band, Elvin had this power.” Farrell, meanwhile, was a relative newcomer to it at the time of this recording. Sometimes he’s ruthless, sometimes it sounds like he’s hanging on by a fingernail.

Revival is far from a perfect jazz offering. But it makes the argument that Elvin Jones’ approach to rhythm, on a foursquare march or a surging modal blues or literally any other groove, endures as something more than a historical-marker archetype. It’s been dissected in granular detail by rhythm players and academics, and we know where that leads: Study under the microscope can illuminate the component parts of Jones’ work, but it doesn’t catch the totality of it quite like a live recording does. This one reminds us, all over again, of Jones’ rare gift for galvanization. He was a catalyst in any situation, on any stage. He was playing the drums, but in fact, his enterprise was the act of energy creation, and energy transfer. He used his instrument to seek out and develop – and then exhaust – highly specific modes of communication. We might think we’re hearing a mad-scientist virtuoso of the kit, and we are. But behind that is something more elemental: the expression of the life force, in exacting rhythm.

Yes, we have a digital suggestion box. Please share your favorite overlooked/underloved records at: echolocatormusic@gmail.com.

Yay!!!

I've always found live jazz records to have a special intangible quality like the music is directed upwards to another realm rather than an error-free take. Hearing musicians go for ideas and concepts before they're fully developed can also give insight into the mind of a musician in a way that a polished recording session can hide. Thanks for turning me on to this.