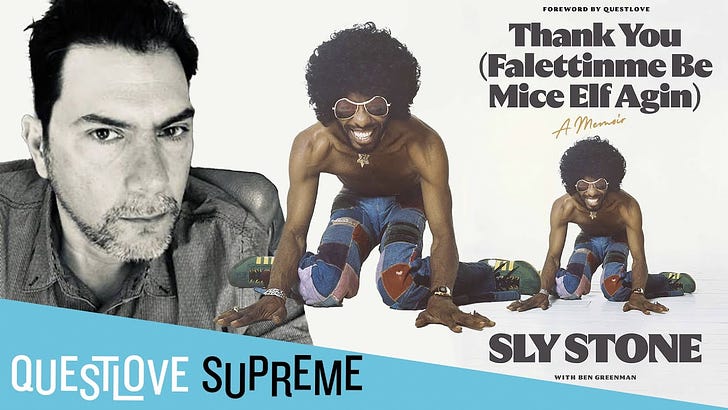

The first miracle of the recently issued Sly Stone memoir, Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin), is, of course, that it exists at all. (See the extensive public record of his decades-long struggles with drugs and its attendant miseries…).

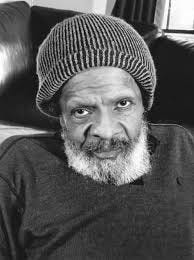

The second miracle is that Stone, now 80 and, according to press accounts 4 years clean, has retained his wry wit and trickster wordplay.

A third miracle is that Stone remembers specific details. His cowriter, Ben Greenman, says he did around 300 brief 15-20 minute interviews with Stone to get the story. That timeframe was apparently all Stone could handle; years spent abusing cocaine and other drugs limited his attention span and evidently impacted his cognitive function.

In the early part of the memoir, Stone, the leader and songwriter of one of the most galvanic acts in pop music history shares his first encounters with key collaborators and bandmates. He remembers some of the recording sessions that led to the many electrifying singles and albums like There’s A Riot Goin’ On.

The moments he’s recalling seem vivid and alive even though they happened more than 50 years ago, and were part of what the press likes to call a “meteoric” rise. The songs of Sly and the Family Stone, unorthodox marvels of verse-chorus concision, were culture-saturating hits. But they endure beyond that, as something more than commercial triumphs: These tunes advanced idealistic messages about human relations, race relations, empathy and brotherhood. They celebrated experiences we share regardless of income or zip code – “Fun,” “Family Affair,” “Life.” Running throughout the provocative riffs and playground taunts was a fundamental, orienting belief in change and possibility.

Underscoring and amplifying the words was a firebreathing band (click the above audio example from Summer of Soul) that embodied the then-much-discussed if little practiced concept of unity. Men and women worked together to make the sound. The band that got filed under “Rhythm and Blues” in record stores had a white drummer. And so on and so on…

That sound had wings. The Sly and the Family Stone songs echoed through — and in many ways defined — the first half of the 1970s. Beloved for their relentless grooves and round-robin ensemble vocals, they influenced countless artists and were known to even the most casual consumers of pop culture. Sly was inescapable. His songs stayed on the radio long after they’d fallen from the charts. When songs lift people up like that and resonate to that widespread degree – a level of ubiquity that only Taylor Swift enjoys today – they become almost like public trusts. They belong to the world.

And then Sly Stone trampled that, squandered it all by himself and disappeared into a reclusive haze that lasted decades. The accounts of his downward spiral are heartbreaking, hard to square with his musical contribution. They’re the all-too-common coda to an uncommon life.

I keep thinking about those short interview sessions, which might have one day focused on a song, the next on the wreckage of Stone’s career and the pain he caused his family. Somehow, though, he continued this inquisition, sifting through the past. That’s heavy for anyone, much less a fallen star who’d spent a second lifetime as an addict.

And speaking of miracles: Sly Stone still remembers the teacher who turned on the lightbulb for him about music.

His name was David Froehlich, a pianist, bassist and composer who taught Stone at Vallejo Junior College. Early in the book, Stone identifies Froehlich as “the first person who made me love music as a language.” He describes Froehlich’s theory classes as starting with the basics of chords and scales, then diving into higher-level ideas about counterpoint and orchestration. “I could get lost in the reading,” Stone recalls, noting that the books were authored by a Harvard professor. “But Mr. Froehlich led me out.” Stone remembers becoming obsessed with everything the teacher said. “I would walk slowly back to my car, trying to get everything clear and then clearer.”

The section on Froehlich lasts only a few pages. But it’s much more than a grace note. It speaks to the ways ideas about music travel from one generation to the next – and how an educator’s patience can activate a young mind, transform a life, and ultimately change the world.

If you love the music of Sly Stone, give thanks for David Froehlich.

If you await the arrival of the next Sly, reach out and thank one of the often-unsung warriors of music education, who work against indifference and under constant threat of cuts to inspire the artists of the future.

Related:

Great writing today, Tom...well done