Tenorio Jr.'s Long Overdue Moment

A gorgeous documentary rescues a samba-jazz pianist from oblivion

Here’s something even the most ardent stalkers of marginalia could not have expected: A full-length animated feature film, distributed in the US by Sony Pictures Classics, devoted to the 1976 disappearance and death of a samba-jazz pianist from Brazil known as Tenorio Jr. – who made just one album during his lifetime.

They Shot The Piano Player, which opened in theaters last week, uses a fiction – the main character is an American journalist named Jeff Harris who learns about Tenorio Jr. while on assignment in Rio for the New Yorker – to tell the real story of a significant talent who was silenced way too soon.

Harris (voiced by Jeff Goldblum) becomes obsessed with the pianist and composer. He begins scrounging interviews with family members and prominent musicians who knew him. He learns about the circumstances of Tenorio Jr.’s demise: The pianist was in Buenos Aires as part of the touring band of legendary lyricist Vinicius de Moraes, and after the group’s last performance, Tenorio Jr. left his hotel on an errand – a risky thing given that the country was under a military dictatorship. Tenorio Jr. was apprehended by Argentinean police; at first the members of the tour could get no information about his disappearance. Upon returning to Brazil, they learned that he was tortured and killed.

The film, by Fernando Trueba and Javier Marsical, comes after several previous Brazilian documentaries (but, as far as I can tell, no New Yorker article) on Tenorio Jr.’s disappearance. Trueba, who conducted the film’s interviews, has explained that he invented the journalist character because he didn’t want to make a typical documentary filled with the somber reflections of relevant experts. The film necessarily has some of those (it’s a complex story!), but the filmmakers’ goal was to bring viewers into Tenorio Jr.’s world, and into the vibrant music community of Rio in the bossa nova 1960s.

They Shot does that and more. It employs a warm, visually stunning animation style that renders some items in a frame with precision, while relegating other elements to colorful splotches in the background. We see the composer Edu Lobo near the piano in his office, with piles of scores around him, and can imagine him working there. We see bright and gorgeous living spaces with transfixing art on the walls, a stark contrast to the shadowy nighttime scenes of Buenos Aires. One sequence features Ella Fitzgerald entering Rio’s famed hotbed of bossa creativity, the Bottles Bar; we watch as she becomes smitten with the sounds, slides through the room, kicks off her shoes and joins the band onstage.

The genius of this storytelling approach is in the linkage between the stunning, playful, rococo cartoon images and the crisp, endlessly modern music. Though many musicians here do, nobody really needs to testify about Tenorio Jr.’s abundant gifts as an accompanist, soloist and composer: Those traits become self-evident as they bubble through the scenes, propelling the action. One wistful, Chopin like original, “Nebulosa,” is heard several times, and each appearance catches different light, its resonances shifting slightly depending on the action.

Those music cues inevitably focus on Tenorio Jr.’s lone album. They also go much further, underscoring the notion (commonly repeated here at Echo Locator) that the full account of a musician’s contribution involves sideman stints and slightly off-brand guest spots. In the film, the journalist’s “conversion experience” happens when listening to drummer Edison Machado’s 1964 debut, Edison Machado e Samba Novo, a landmark small-group set that is one of the great examples of Tenorio Jr.’s smoothly syncopated accompaniment style. Where other pianists set landmines for soloists, he's deliberately seeking dialog, delivering tense voicings with absolute rhythmic authority. There’s no guesswork when he is involved. And the piano solos, on “Miragem” particularly, occupy an elevated airspace, with Tenorio Jr. avoiding glib eighth-note bebop to pursue a coy, restrained fantasy built on quarter-note triplets.

Tenorio Jr. was among the musicians involved in “opening up” bossa nova by incorporating modal harmony and elements of hard bop, samba, and rock music. He was in high demand in 1964: In addition to the Machado album and his own Embalo (with some of the same musicians), Tenorio Jr. worked alongside Deodato and guitarist Roberto Menescal on Vagamente, the cult classic by vocalist Wanda Sa, as well as the O LP by Os Cobras, which features drummer Milton Banana (who was part of Tenorio Jr.’s trio).

This pianist had a rare knack for guiding the music without asserting himself from measure to measure: When supporting vocalists, he mostly lurked in the background, yet occasionally slipped in perfectly apt asides or unexpectedly tense harmonies. Tenorio Jr. perfected this intermittent invisibility as time went on; by the early ‘70s he was part of the musicians collective known as the Clube da Esquina, adding sparkling and short bursts of piano to the self-titled debut of Lo Borges and electric piano to another cult favorite, Nelson Angelo e Joyce, serving as a foil to guitarist/pianist Egberto Gismonti on the rivetingly cinematic Arvore and the followup Academy of Dances.

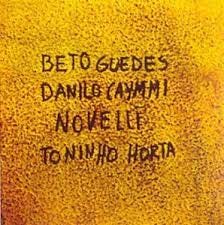

Two other works that benefit from Tenorio Jr.’s lowkey presence: The plaintive and gorgeous round-robin work Beto Guedes, Danilo Caymmi, Novelli, Toninho Horta – which is desperately overdue for reissue, the above YouTube link is alas what’s available now – and Gal Costa’s gem India. Both are from 1973, and reflect the creative flowering that followed the release of the world-changing 1972 double album Clube da Esquina. Both have flashes of Tenorio Jr. – the former contains a riveting piano solo on Danilo Caymmi’s “Ponte Negra.” Both loom as significant achievements now, works defined by stunningly stretchy vocal melodies and unconventional shape-shifting instrumental textures. It’s not surprising that Tenorio Jr. was a participant.

There’s much more to say about They Shot The Piano Player. With characteristic understatement, it offers a haunting glimpse of what can happen when a country is subject to autocratic rule – in a real sense, Tenorio Jr. was the victim of two dictatorships, the one that repressed creativity in Brazil, and the one that killed him in Argentina.

Unlike some other recent films about artists (looking at you, Maestro), this one avoids hagiographic worship in favor of human detail – it shows Tenorio Jr.’s family decades after his death, still grappling with the loss, and by lingering over conversations and eye contact, conveys the warmth and saudade of what is one of the world’s great music cultures. This savoring approach sharpens the viewer’s sense of the man, transforming the ”obscure talent meets tragic end” storyline into something more nuanced, something that we see affected various members of the community in deeply personal ways, yet was also, crucially, shared.

Not to overlook the way the film slyly enters the ongoing conversation about the “death” of music journalism, giving a hallowed institution a delightful little spanking. The picture celebrates the New Yorker as a place where serious journalism and criticism about the arts happens – hey, the tragic story of Tenorio Jr. is precisely the kind of thing you might have encountered in the pages of the New Yorker. But that key part of the story is fake. That story didn’t happen. Lots of stories about contemporary music don’t happen there. It’s worth asking: Why not?