The other day I encountered this clip of Billie Eilish and her brother doing an intimate Julie London-style interpretation of “I’m In the Mood For Love.”

It’s the latest in a line of exceptional cover versions that stretches back to 1935, when the song, written by Jimmy McHugh and Dorothy Fields, was premiered in the film Every Night at Eight.

Listen to just about any of the hundreds of interpretations between the Francis Langford original and the hushed Eilish, and it’s clear why the song has endured: It’s a graceful yet somewhat elusive melody, made less “stock” by a few direction-changing half steps that create crucial tension. The chord sequence is similarly elusive: It shares traits with songs by Irving Berlin and other Great American Songbook composers, yet contains one or two unconventional, ear-perking twists – the kind jazz improvisors eat for breakfast.

A great song is a template. A chain. A vehicle designed for the exploration of truths fleeting and enduring. Over time, great songs teach us that inspiration is less about an isolated lightbulb-blinking event than a constantly renewable circuit running in multiple directions at once, a protracted esthetic conversation between people of different eras, backgrounds, sensibilities.

It’s humbling to think about the hundreds (maybe thousands?) of versions of this one song, and how each seems to draw out striking individual interpretations. Will any composition created in 2021 ever inspire that kind of discourse? If not, why not? Can the endurance of Great American Songbook standards be explained just by the structural frameworks of the tunes, the sturdy simplicity of the melodies? Are new compositions somehow less transferable from one artist to the next because of the specificity of modern production? Or should we just blame the mind-numbing torrent of new songs that flood the Internet daily?

Just consider a single creative tributary sparked by “I’m In the Mood For Love.” The tune had been mostly covered by singers until bebop pioneer Charlie Parker began playing it in the late ‘40s. That caused many modern jazz players to learn it – among them a young, prodigiously talented Parker disciple named James Moody. In 1949, at the end of a long day of recording with a pickup band (the Swedish Crowns) in Sweden, Moody suggested “I’m in the Mood For Love.” They did one take, and it’s notable for Moody’s spry, unapologetically lyrical phrasing. The jazz world took notice when that version was released; among the admirers was a vocalist named Eddie Jefferson who’d developed an unusual knack for creating narratives out of intricate instrumental jazz solos – a style known as vocalese, which contrary to some histories Jefferson did not invent. (Some consider a singer named Bee Palmer to be the originator, for her version of the 1920s-era Bix Biederbecke hit “Singing the Blues.”)

Jefferson memorized the leaps, turns and contours of Moody’s solo, added words about being lovestruck, and began performing it as “Moody’s Mood For Love.” That version spread the Moody magic further: Within a few years, the suave vocalist known as King Pleasure recorded the Jefferson lyrics, and the song became a big, lawsuit-provoking hit. (McHugh prevailed.)

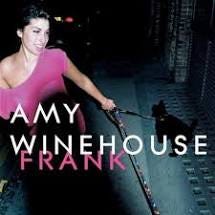

Since then, “Moody’s Mood For Love” has evolved into a litmus test of sorts for singers – jazzers depend on it to demonstrate their intervallic dexterity, while rock singers (Van Morrison, Rod Stewart, others) have gussied it up to show “range” or something like it. Among the less-than-stunning versions is Amy Winehouse’s take, a misstep on the 2003 studio album Frank: Though she soars through the challenging leaps, the backing track remains earthbound, the loop crowding out and stomping on the subtle, athletic twists she brings to the theme.

Then there’s its opposite: A ripping 1986 live recording by the late Washington DC guitarist and go-go music visionary Chuck Brown with his band the Soul Searchers. Brown was a rudimentary singer, a club belter whose specialty was getting people moving, singing, interacting. He adapted the melody to the hard-swinging funk pulse of go-go, and just kept riffing, pushing the tune away from the songbook and into a deliriously sweaty last-set audience participation extravaganza.

But here’s the thing: It has some 1935 in it, but it’s not some quaint respectful revival. It celebrates the McHugh melody and some of that King Pleasure wryness and a touch of Wes Montgomery and a dash of that royal Aretha Franklin poise. It’s aware of the long chain of interpretations and interpolations, but it’s fully alive. And when you get swept into that go-go groove, you realize it’s not any one thing. It’s not just that melody, or the indelible Moody solo, or the way Brown keeps kicking things higher.

It’s all that and then some — a circuit of inspiration, running pretty much unbroken for a long time, that makes you want to hear where it will go next.

Why yes, we have a fancy digital suggestion box. Share your favorite Underloved/Overlooked records here: echolocatormusic@gmail.com.

Please consider subscribing (it’s free!). And…..please spread the word! (This only works via word of mouth!)

Such a brilliant analysis! I love al o fit, but especially this part dealing with Chuck Brown (I'll look for his version): "But here’s the thing: It has some 1935 in it, but it’s not some quaint respectful revival. It celebrates the McHugh melody and some of that King Pleasure wryness and a touch of Wes Montgomery and a dash of that royal Aretha Franklin poise. It’s aware of the long chain of interpretations and interpolations, but it’s fully alive. And when you get swept into that go-go groove, you realize it’s not any one thing. It’s not just that melody, or the indelible Moody solo, or the way Brown keeps kicking things higher."