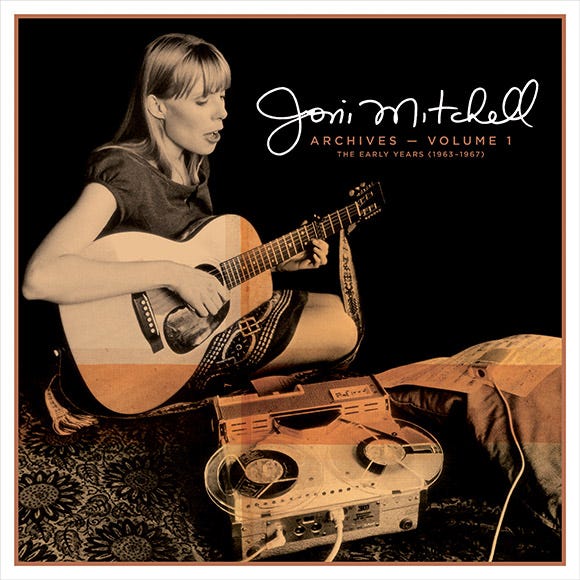

On the Occasion of the first release from the Joni Mitchell Archive

At last, a map to formative early work from one of popular music’s most original voices.

The first installment of the long-promised Joni Mitchell career retrospective has arrived. The five disc set offers a chronological tour of her beginnings as a singer and songwriter, gathering live performances, radio chats and demos from 1963-1967 — many of them rendered in surprisingly crisp audio. This timeframe covers her days as a folk singer in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan – before she rejected the “folk singer” tag – and captures her surprisingly swift transition from interpreting the works of others to crafting her own songs.

Though it starts with some dire minor-key dirges (Merle Travis’ mining classic “Dark as a Dungeon”), The Early Years portrays Mitchell as a resolutely bright and earnest artist, curious about the world and anxious to contribute to, and shape, its sonic landscape. There’s much to savor in the performances and song introductions across each disc of the collection; below are some notes I’ve scrawled while listening and re-listening and then listening some more.

She studied. To understand the path of an artist, it helps to know a bit about her origins. That context has been somewhat obscured in Mitchell’s case by her incandescent original songs, which tend to tower over any antecedents. This set shows that Mitchell arrived at her “voice” after working up and regularly performing a repertoire of vital if lesser-known tunes from the folk songbook. She burrowed into the cadences, found the points of emotional emphasis, and absorbed (and later repurposed) the chord sequences. It’s possible to trace some at least dotted lines from her renditions of “The Crow On the Cradle” and “The Dowie Dens of Yarrow” to her creations on Blue or Court and Spark; the musical traits of those old tunes contributed to her musical language.

And her inspiration didn’t just come from folk: In the extensive notes, which include a new Mitchell interview with Cameron Crowe, she says she drew inspiration for her song “The Circle Game” from Neil Young’s “Sugar Mountain.” For those who like to connect dots, there’s a thrilling Mitchell treatment of “Sugar Mountain” here.

She valued the first bolt of inspiration. In the 1970s, Mitchell labored over her records, focusing on detail. In her early years, she was more focused on capturing and repeating the electricity of an idea, regardless of the arrangement or ornamentation around it. She integrated her new songs into the live show as soon as she felt they were ready, and she continued to work on small aspects like phrasing and structure when she performed. That was common among folk artists at the time; less common was the unselfconscious exuberance she shared about her compositions as she introduced them. One 1967 performance, on Philadelphia radio, happened just days after she wrote “Both Sides, Now.” In conversation with host Gene Shay, Mitchell sounds excited and gratified to learn that someone requested the tune. “I’ve been driving everybody crazy by playing it twice and three times a night,” she says. That’s the mark of a hit.

She honored time. No matter how high into the stratosphere her voice goes, or how much vibrato she uses (lots at the beginning!), Mitchell never gets so lost in the demands of the vocal that she neglects the timekeeping role of the guitar (or ukelele). There’s real highwire-act art to performing alone, and by 1967, Mitchell had mastered it.

She did not limit her songs. In 1966, Mitchell wrote a song about the soul-crushing winters in Saskatchewan. The image-rich lyrics of “Urge For Going” caught some truths about the impulse to escape when they were first recorded by Tom Rush. But his version is fairly declarative. The Early Years contains several live Mitchell treatments of “Urge For Going,” and while they retain her initial meaning, they find her glancing at all kinds of other things that fall under the heading of feeling trapped. They’re notably more dimensional.

She grew rapidly. First Mitchell studied the nuts and bolts of folk songs, touching on British ballads, laments, and war narratives with verse after verse. Then she used the sturdy templates of the folk canon for mulch, transforming them into her own sophisticated, instantly identifiable musical language. That’s where The Early Years ends; her debut was issued in 1968. From there, Mitchell developed the disarming confessional hues of Blue (there’s a great early version of that album’s “Little Green” here). And then the more floral, vivacious full-band work of Court and Spark. And on and on, through challenging multi-tracked vocal tapestries to her adept genre-blind re-imaginings of the music of Charles Mingus to the trenchant cultural commentaries embedded in her ‘80s and ‘90s output. It is an incredible evolutionary journey unlike any other in the history of pop music; to fully appreciate its sweep and gauge its impact, you kinda do have to start where she started.

In the Crowe interview, Mitchell reflects on her rejection of that folk singer designation: “Musically I grow, and I grow as a lyricist, so there’s a lot of growth taking place. The early stuff – I shouldn’t be such a snob against it. A lot of these songs, I just lost them. They fell away. They only exist in these recordings. For so long I rebelled against the term: “I was never a folk singer.” I would get pissed off if they put that label on me. I didn’t think it was a good description of what I was. And then I listened, and – it was beautiful. It made me forgive my beginnings.”

Side note for those wanting the full music-geek plunge into the depths: On Mitchell’s website, there’s a button “Lyrics and More” for each track. In many cases, the “More” means anecdotes, lists of cover versions and relevant context. Set aside some time.