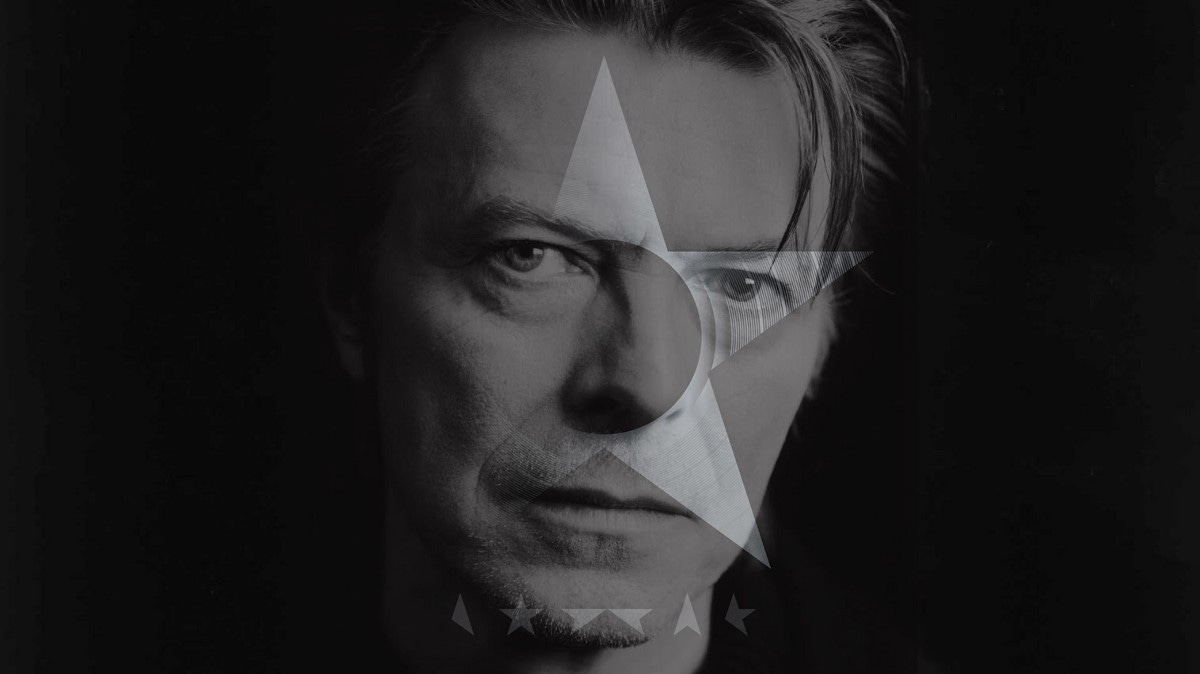

On David Bowie: Empty Voids and Doubt, Presence and Absence

There’s more, always more, going on in the background while Bowie works the front of the house

There’s more, always more, going on in the background while Bowie works the front of the house

The jottings take up most of a notebook page. They’re from the first time I listened to “Blackstar,” the opening track from David Bowie’s album of the same name. I had no assignment, no obligation to write anything. Typically I wait until I’ve heard something a few times before scribbling, but in this case I couldn’t help it. The sounds, which will stand as the last music Bowie issued during his lifetime, were eerie and curiously off-center, compelling and repellant all at once. I badly wanted to figure them out.

Among the scrawl I can make out on the page: Vocal all hollow, like church harmony—Gregorian chant? Dark and then more dark. Candles and incense… are we about to have ritual sacrifice, a death mass? Talking how he’s not a pop star, he’s a black star—please don’t let this be a concept album about stardom. Dissonance in layers. Processional tempo… approaching gloom… here that wordless vocal really works, his voice is closer to the foreground. Band takes it out into ozone at the end… Bowie tho is disengaged, icy, deliberately out of focus, a vapor trail.

At first that detachment, which is audible in varying degrees across the album, made me wonder about Bowie’s investment in the music. Was the Thin White Duke finally phoning one in? Did the improvisational aspect of the project (his collaborators include jazzers Ben Monder, Mark Guiliani and Donny McCaslin) give him permission to step away from ringmaster duty and operate in the margins a bit? Had he grown bored with the audience’s expectation of a new lineup of personalities with each album?

Then, as always happens with Bowie, I began to burrow into the tune, and the entire unsettling yet strangely peaceful album. Looking for a quick way to summarize it. This eluded me, and I was not surprised. Among his legacies as an artist is the deserved reputation for being difficult to parse. At a time when so many create work that can be fully understood, digested and eliminated in a day, Bowie always made you think. Wrestle with the first impression, and then doubt the second. And then, a month later, re-evaluate everything.

In that way, Blackstar, with its tangled messy genius knots of death-haunted sound, was just like every Bowie project. But we didn’t know it was being made by a death-haunted soul. Now we do. Is it more profound that way? Ask me in a year. I still won’t have fully understood the choppy and dissonant sound, with saxophone notes flying around in torrents and the beat jagging slightly off-grid like a car with barbed-wire wheels. It scrapes the ears hard.

As his followers know, there’s more, always more, going on in the background while Bowie works the front of the house—levels of meta concept and commentary, droll observations about mundane things, clues to the meaning of life. This person always did more than merely write songs — he used every available expressive device to engage and remake and disfigure established forms. Including making himself scarce, or invisible, or inscrutable.

He was good at the magician’s skill of misdirection. Most pop artists peddle sincerity — he specialized in empty voids and doubt, presence and absence. He was the outsider for whom there really wasn’t an inside or a comfort zone. With Blackstar, he created not so much new roles but a new spatial distance from the listener—at times it feels like he’s some kind of hologram, speaking from beyond the grave, a differently theatrical spirit guide whose thoughts ooze between the street-level chaos of the band. He’s here, and not here. Locked in the groove and then swallowed by sound, by feeling, by towering persona and enigmas of his own creation. In sync then abruptly out of sync.

The biographies tell of the many times Bowie overhauled his music and image and how, in the process, he routinely confounded his audience. He did more than that, though. He showed the pop world—specifically Madonna, Lady Gaga, Miley Cyrus, et al—something crucial: That such recalibration resonated best when it was rooted in and integrated into the act of art-making itself — i.e., when it wasn’t just trend-hopping. Bowie didn’t merely change costumes with the times; he shifted everything about his work.

His reinventions were complete overhauls — he’d emerge with a new sound and a corresponding new harmonic vocabulary, a new set of rhythms, and a wholly different lyrical strategy, and leave it to listeners to sort things out. It can be difficult to believe that the singer who slinked through “Young Americans” is the same one singing about “Sufregette City” is the same one intoning grimly on Blackstar about “Lazarus.”

Where other artists followed the rules of whichever genre they were visiting, Bowie went the other way—his investigations transformed the genres. To wit: The dark sound-paintings of Low started out evoking the somber and solemn foreboding of a strain of German electronic music. But as it unfolded, from far across the tundra of sound, Bowie introduced a distinct (and distinctly disquieting) vulnerability that is only present here, on his records. He covered the expectations and specifications of the genre and didn’t stop there—he added other levels, gave his stances serious dimension and often menace, furnished his narratives with meta-conceptual overlays. And like an impressionistic master, he used implication and nuance, shading and pastel colorations, to fill out the terrifying and beautiful images.

Bowie did this serially, over and over, across decades. Not every transformation was a smashing success. Not every move was understood. But right on through the shadowy Blackstar, with its croaking entreaties “Look up here, I’m in heaven,” his work is notable for what it says about art and inspiration. A significant part of his legacy is in the ways he went about being an artist. His restlessness. His refusal to stay in one place. He brought sophisticated art-world radicalism to pop, and in borrowing those technique, he captivated listeners—and challenged them at the same time.

Sure, study the records, they’re brilliant. But also study his choices, his thinking, the path he took as an artist. His example as a musical seeker, provocateur and destabilizer doesn’t seem to have many followers right now. We could sure use a few.

If you enjoyed reading this, please log in and click “Recommend” below.

This will help to share the story with others.

Encountering Miles

How I got a lesson in art, aesthetics and improvisation from the jazz legendmedium.com