On Becoming a Disciple of The Earth Disciples

Another little-known '70s band with lessons for modern musicians

Somewhere, in a little-visited storage facility in a tertiary market suburb, there’s probably a box containing the studio invoices and marketing plans and other details surrounding the only album by The Earth Disciples.

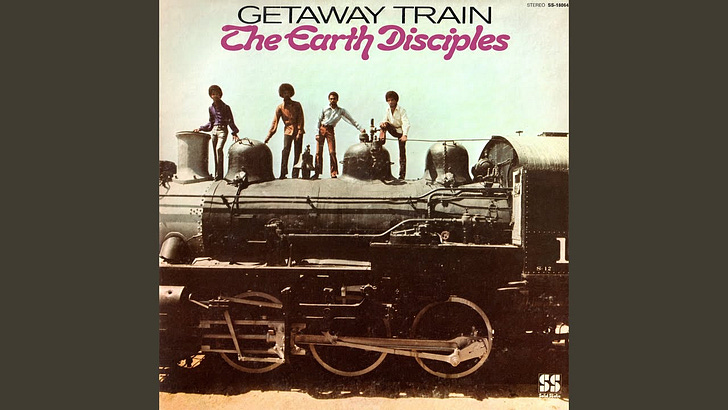

Such an archive would hold the basic information, documenting how Getaway Train was made by a four-piece instrumental group (apparently) based in Southern California; at the time of the recording in 1969, three of its members were just 19 years old. The album was produced by the saxophonist Dave Pell – who was still dining well on royalties from his work on Alvin and the Chipmunk’s 1965 Chipmunks A Go-Go. That’s the one that included covers of Bob Dylan’s “Mr. Tamborine Man” and Tom Jones’ “What’s New Pussycat.”

Oh yes, we’re going there! How else to contextualize the crazy confluence of the sublime and the ridiculous that (partly) defines the music industry of the 1960s?

Maybe that dusty file contains (likely disappointing) sales figures for the album, one of the last issued by the Solid State label before its artists were transferred to Capitol or Blue Note. Or dropped, like The Earth Disciples. Maybe there’s a memo from the legal department about the cover shoot, which involved the musicians standing atop a vintage locomotive. Maybe there are newspaper clippings from a big 1970 LA show when the Earth Disciples opened for Steppenwolf.

There are (or were!) countless files like this from the old music business. They’re the prosaic, unfortunately all-too-common profit and loss chronicles of hopes and dreams crashing – the label’s inability to connect artist with audience, the band’s inability to build a following. Radio’s reluctance to get on board. And so on and so forth.

What happens after the case is closed and the record lands in the cutout bins of Woolworths everywhere? That’s up to the music itself.

When you drop the needle, do the sounds add up to a flashing “Relic” sign, warning modern listeners to stay away? Or do they do what Getaway Train does – gently but firmly suggesting “Hey! You guys missed this!” over and over again? This record sends that message in different ways on literally every track. It’s like no jazz-adjacent thing being made today – the players all have chops but rarely flex them. It’s a calm, chill endeavor – until its simplicity inspires outbreaks of brain-melting genius. It’s music guided by a stealthy appreciation for understatement. It’s accessible and spiritual and grooving all at the same time. Listen:

Check that electric piano, played by a musician named Rudy Reid who wrote many of these pieces: His crisp Morse code stabs establish a solid structural framework, which he embellishes with delicate dancing lines that add sparkle around the edges of the music. (These tactics are, of course, shared by many 70s-era keyboardists, including Joe Sample with the Crusaders, and Donald Fagen of Steely Dan.) Check the guitar improvisations of Jimmy Holloway (son of saxophonist Red Holloway), which combine the scene-stealing theatrics of rock guitar titans with the melodic purity of Wes Montgomery serenely playing octaves. Check the way drummer Reggie Harris creates drama with measured press-roll surges at the opening of the title track – and then locks into a groove that might seem generic (could be “Rock 3” on a Casio keyboard!) but is in fact almost meta in its subversions, its slight and randomly occurring backbeat-chopping variations.

The Earth Disciples might have been young, untested by the business and all the rest. But this group made a classification-defying record (is it funk? prog-soul? jazz fusion?) that offers profound and still relevant ideas about ways to captivate listeners who might not be drawn into the grandstanding extended-length heroics common in modern improvisational practice. The songs are mostly short. The melodies are simple declarations; most are singable. There are frequent shifts between tempo and rubato, and double time to half time; the four move together as a cohesive unit, executing transitions between sections and grooves with offhand nonchalance. And they do that even when the compositions demand more extroversion and intensity.

No amount of hindsight rationalization can completely explain how Getaway Train remains largely unknown. Some bloggers have championed it: Years ago a British writer named Seb Palmer prevailed upon the surviving band members to share music from an unreleased second album, Universal Man. This song, “See The Earth In Space,” the planned (and unfinished) album’s opening track, was posted on Palmer’s SoundCloud:

And despite the fact that vinyl copies are scarce (and there’s no reissue yet), The Earth Disciples have been noticed by DJs and hiphop producers: The legendary Pete Rock snagged “Getaway Train” for his 2015 track “Heaven and Earth.”

And….that’s about the extent of The Earth Disciples’ digital footprint. By some miracle, Getaway Train is on streaming services. Cue it up, and prepared to be amazed by yet another record that has a 1970s timestamp but sounds gloriously, defiantly timeless.

Nice highlight on a little-known jazz funk album (that leans more on the loungey side, but with some scorching guitar licks). It is certainly well due for a reissue, and I am sure it will (everything seems to these days).

Excellent stuff, Tom. Great discovery. Thanks for sharing.