On a (Seriously Altered) Mardi Gras, Reflections of a Vital Music Culture

Ann Savoy's exhaustive second volume offers roadmaps for Wayback exploration....

Yesterday’s New York Times had a story about the ways the pandemic is impacting Mardi Gras in New Orleans, a yearly rite since 1857. The customary Fat Tuesday parades through the French Quarter are cancelled this year, but the piece described how many of the city’s Indian tribes are adapting and reconfiguring celebrations. Cherice Harrison-Nelson, the Big Queen of the Guardians of the Flame Mardi Gras Indians, explained that her group would walk in a socially distanced procession through residential neighborhoods.

The goal: To salute elders outside their homes.

This won’t be surprising to anyone who knows the culture of Southern Louisiana, where respect for community elders is entrenched and cultural traditions are regarded as vital tethers in daily life. Harrison-Nelson describes the city’s parade groups as “spiritual first responders.”

New Orleans and its vast surrounding area tends and cultivates its indigenous culture. Daily. In ways large and small. Kids grow up knowing who Louis Armstrong was; many of them take up instruments in hopes of playing in the brass bands that serve as catalysts during the parades and offer consolation on the long walks of jazz funerals.

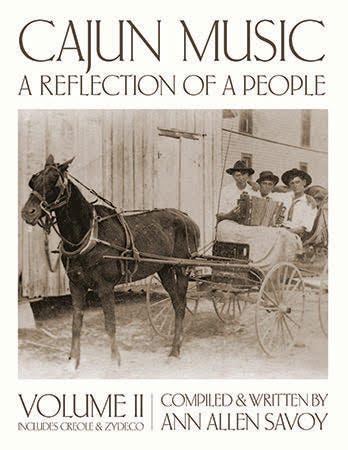

Further proof of this guarding-the-flame mission: This week brings the second volume of musician and historian Ann Savoy’s Cajun Music: A Reflection of a People, the followup to her landmark collection of oral histories, rare photos, songs and stories published in 1984.

The book gathers the significant, if forgotten, characters who developed the graceful waltzes and peppery uptempo two-steps that define Cajun music.

It’s not intended as an encyclopedia. In a recent interview in the Louisiana Advocate, Savoy explained that she concentrated on the elders and the pioneers of the multi-cultural dance musics that flourished in bayou country after Acadians from Nova Scotia and other parts of Canada settled in Louisiana in 1764. ““It’s not a reflection of who the most important artists are,” Savoy told journalist John Wirt. “And I don’t put modern people in there, except a couple of Creole and zydeco guys. I usually don’t put any young people in my books. That’s kind of the rule. I’m documenting the old folks, the ones who created the music and made it what it is.”

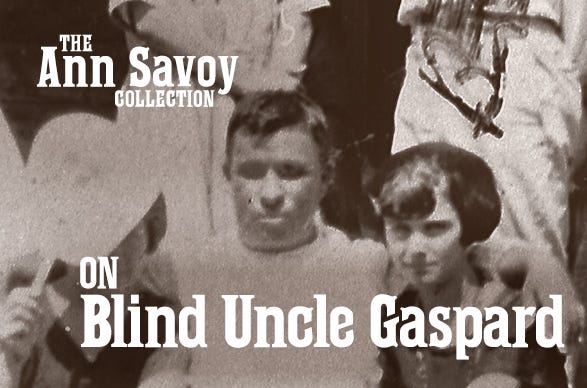

Savoy covers every detail of the music-making, and includes transcriptions of some landmark songs. There are sections on the lyrics, the dances and social gatherings, the rhythms and the instruments (her husband, noted accordionist Marc Savoy, contributes a history of the accordions and a description of the instrument’s function within the music). The oral histories provide insight into the lives of the music’s creators – and their audiences — during decades when live music was at the center of social life. In addition to those long, anecdote-filled sections, Savoy offers short biographies of figures like Alcide “Blind Uncle” Gaspard, a guitarist and multi-instrumentalist who was revered in his lifetime (he died in 1937) despite a tiny discography: Archivists have only found five recordings with his name attached to them.

By some unexplained miracle, a few of them have made it to Spotify. This short introductory playlist (link at the top of the page) includes two featuring Gaspard and some others mentioned in Savoy’s list of “Recordings Used in This Book” appendix. One exception: The closing Professor Longhair track, which picks up on the works featured by Savoy while offering a (slightly) more modern perspective on the unextinguishable spirit of Louisiana music.

For further exploration: Follow link to Savoy’s archive.

Yes, we have a fancy digital suggestion box. Share your favorite Underloved/Overlooked records here: echolocator@gmail.com.

Please consider subscribing (it’s free!). And…..please spread the word! (This only works via word of mouth!)