Last week in my Twitter feed, a recording artist shared that he’d cued up Steely Dan’s Aja as a reference when setting up his whole-house audio system. That was followed by a confession: He was about to do an interview with a publication that last featured an interview with the British art-pop group Supertramp, which was active contemporaneously with Steely Dan but not nearly as hip. He worried that he’d become a walking dad-rock cliché.

Ah Supertramp. Punchline then. Punchline now.

Maybe it’s the name. Or the overweening earnestness of the band’s often-covered single “Give A Little Bit.” Despite a string of inescapable hits in the late ‘70s, despite a catalog of ambitious, sonically expansive records that combine ear-candy pop hooks with grand and sometimes inventive prog-rock interludes, Supertramp has not managed to snag the major classic-rock-artist respect.

Just how bad is this respect deficit? According to the discographies on streaming sites, Supertramp’s career began with Crime of the Century in 1975. It’s a riveting listen, an album in the old-school sense of the term, with interesting juxtapositions of mood and narrative. There’s drama in it from the first harmonica wails to the last piano sustain.

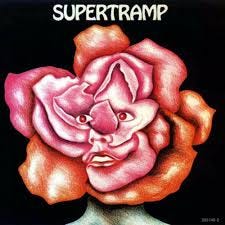

Just one thing: Crime is the third Supertramp record. The first two, Supertramp and Indelibly Stamped, were also released by A&M; they are missing from Spotify and Apple Music and the other streaming platforms. A lucky bit of counter-intuitive searching turned up a listing for the second album on Spotify – but only one track is available. Here is a link to the debut provided by some fan on YouTube; I’m reluctant to share it because, obviously, the band gets no financial renumeration from it. (Some have suggested that Supertramp’s management has been aggressive in taking down unauthorized versions of those titles and others.)

Still, these works did happen, and they make fascinating listening. They’re mentioned (albeit disparagingly) on music database sites like allmusic.com. No matter what Spotify says or whatever explains their absence, they exist as part of the historical record. I’d argue that access to these once-commercially-available titles is important. Because after delving into Crime of the Century and the band’s multi-platinum commercial peak Breakfast In America, a curious listener might wonder what the band sounded like in its early days, when nobody was listening and the canvas was blank. Where did the primary singers and writers, keyboardist Rick Davies and multi instrumentalist Roger Hodgson, begin? What changed as they evolved?

Those points of origin matter in music. They enable us to trace the pursuit of an idea or a sound, sometimes over years of trial and error. They show how artists respond to trends in the culture. Even the detours and dead-ends – alas, much more common in previous eras -- teach something about the leaps a band took, and what happened after those leaps.

The Supertramp debut, which was released in 1970 (four years before Crime of the Century), is not a masterpiece. But those who admire the intelligence and craft that animates the better-known Supertramp works will detect seeds and sprouts within these songs. There are downtempo pieces (“Aubade/And I Am Not Like Other Birds of Prey”) that turn on bracingly lovely vocal harmonies, and songs that start out modestly then balloon into epic journeys (“Try Again”). One tune, the blues-dusted “It’s A Long Road,” sounds like the members of Supertramp were enthralled by the early explorations of Traffic (“Feelin’ Alright” was on the radio at the time) and also by Then Play On, the dizzyingly creative then-current release by Fleetwood Mac. At a particularly fruitful moment in British rock, these guys eventually went their own way — pushing thick stacks of keyboards to the forefront, with electric guitars in the background — but they didn’t do it in a hermetically-sealed bubble. They absorbed what was going on, and from that inspiration created something distinctly original.

There are probably many similar connective threads waiting to be pulled between the musical characteristics of Supertramp (or the compositionally less compelling Indelibly Stamped) and the majestic sprawl that defines Crime of the Century and everything that followed. And that’s the thing: Now that the entire history of music is searchable on the Internet, and the streaming services argue for their very existence by promising the deepest of deep dives, it’s reasonable to expect a degree of comprehensiveness – particularly when it comes to the catalogs of artists who sold boatloads of records. In this age of ever-expanding data storage, anyone who was ever thrilled by the pulsating electric piano chords of “The Logical Song” should be able to follow the steps Supertramp took to get there. That means all the steps. Including the less-commercial first ones. Maybe especially those.

Yes, we have a fancy digital suggestion box. Share your favorite Underloved/Overlooked records here: echolocatormusic@gmail.com.

Please consider subscribing (it’s free!). And…..please spread the word! (This only works via word of mouth!)