Malware For All!

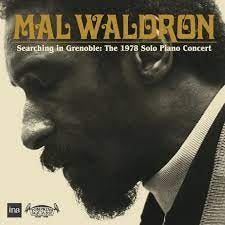

A previously unreleased solo concert by pianist Mal Waldron

A tense piano chord lands on the downbeat. It’s fierce, declarative, a statement by itself. Played with clarity and intent the first time, the chord is approached from various rhythmic angles. Then the pianist Mal Waldron turns it into a short telegraphic code, the outline of a theme. Which he then repeats until it ever so slowly morphs into something else.

Versions of this pursuit happen throughout the intense and not always straightforward Waldron performances on Searching In Grenoble, a previously unissued concert from 1978. There’s truth in this title: Waldron is indeed searching, but not in a casual let’s-see-what-turns-up way. He is asking fierce questions of his instrument – and his intellect – as he goes along, and those are explored in a patient and deliberate way. Stealth like a hunter, he moves in wide circles around the melodies, his melodies. Sometimes he’s blunt, sometimes he employs diversion tactics. Concentration is needed to follow his tracks.

On “Snake Out” and other astonishments from that night in Grenoble, Waldron practices an approach to real-time motific development that is about a million miles from show-business jazz piano. He’s exceedingly deliberate, repeating short rhythmic figures until they become incantations, petitions to long-neglected deities. He abruptly shifts away from the tempo to take time out for some brooding. There’s a tactile element to his phrases, and it’s reinforced by the excellent recording: He’s clawing at ideas, or breaking them down to their constituent intervals, or gliding right past them on the way to greener pastures. Following his moves in real time, you get the sense that Waldron doesn’t want to think much about where he’s going, that the pleasure for him lies in plotting what might become an endless chase. He scatters cocktail-hour pleasantries across his most-played tune “Soul Eyes” – and just when you think that’s the game, he dives into a chorus of single-line playing that reaches deep into his iconoclastic bebop trickbag for a series of brain-scrambling, often unresolved forays.

Searching In Grenoble has been out for about a month, and already it has prompted a resurgence of interest in Waldron, another jazz titan who, despite an extensive discography and a distinctive style, has been hiding in plain sight. The pianist came up in the hard bop era – for a time he was the house pianist at Prestige Records, and appeared on landmark records by John Coltrane, Eric Dolphy, Gene Ammons, Charles Mingus, and Max Roach as well as blazing lesser known works like Cattin’ with Coltrane and Quinichette, recorded in 1957 and released in 1959.

During that same period (1957-59), Waldron served as Billie Holiday’s accompanist – he appears with her on the 1957 TV show The Sound of Jazz, one of the first times the music was featured on network television. Waldron’s most celebrated date as a leader is The Quest, a 1961 release featuring multi-instrumentalist Dolphy, saxophonist Booker Ervin and Ron Carter (on cello!); among the originals is “Fire Waltz,” which Waldron methodically unravels and re-assembles as part of his Grenoble concert.

The turn in Waldron’s story happened in 1963, when the pianist, a heroin user at the time, suffered a significant mental breakdown triggered by an overdose. As he recalled in a 1998 New York Times profile, “I couldn't remember my own name. My hands were trembling, I couldn't play the piano. I needed shock treatments and a spinal tap to bring me back.”

Waldron spent years in rehabilitation. He transcribed his old recordings to teach himself how to play again, but as has happened with other improvising artists who suffered neurological setbacks (Pat Martino), the pianist’s playing transformed in striking ways. His chords got thicker and more tense; he frequently swerved from single-note runs into elaborate and deeply polyrhythmic inquisitions notable for their stomping, insistent quality. When he returned to an active schedule of recording and performance, he took on different musical challenges – exploring a freer, more European discourse in small groups (his 1969 trio date Free At Last is the very first title released by ECM Records) and doing regular solo piano recitals.

During the ‘60s and ‘70s, touring for jazz musicians wasn’t always oriented around album releases – the players traveled widely, recording when and where they had opportunity. Waldron’s Grenoble performance, captured by French radio, was in late March. By early May, he was in the studio recording both solo and with a quintet featuring his longtime collaborator, saxophonist Steve Lacy. (Their duo recordings will get their own Echo Locator shrine sometime soon…). This session, initially released as Moods and reissued in several configurations, stands among Waldron’s most luminous recordings. It’s an excellent prismatic counterpoint to Searching at Grenoble that showing how, in the hands of a wiley musician like Waldron, the same tune can come alive in radically different ways depending on the day.

Yes, we have a digital suggestion box. Please share your favorite overlooked/underloved records at: echolocatormusic@gmail.com.

Great post, thank you

Waldron co-wrote 'Quiet Alone' with Billie in 1957. It's the only song she composed but never recorded

Deborah Brown's cover: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XeZzgUouoVc

Thanks for this treat!!