Long Way from Coolsville

on the recent memoir from Rickie Lee Jones

Page through any recent issue of Rolling Stone magazine (or any other outlet devoted to popular culture and music), and it doesn’t take long to confront a sobering reality: We’re running out of characters.

Sure, the music press brings us nicely attired aspiring stars by the bucketful. But what are those artists offering? Most are engaged in some version of paint-by-numbers musicmaking. We’ve got marginally talented people being groomed by imaginationless middle-manager types who confuse the outlandish with the artistic. We’ve got celebrities working every angle (including, alas, the one marked “batshit crazy”) to increase market share.

What we’re losing, rapidly, are the defiant, proudly zany, bracingly original, not-always-there-to-please voices – artists like Frank Zappa, who developed not just sounds but entire cosmologies, whose work questioned every foundational assumption of the industry.

Look around at the undifferentiated striving that defines current popular music, and it seems almost incredible that an artist like Dr. John had hit songs on the radio in the ‘70s, songs culled from delightfully greasy albums that celebrated New Orleans culture as a psychoactive pathway to enlightenment. Or that there was a sizeable audience for the wry ten-levels-deep songs of Lyle Lovett. And on and on. These were people who marched to their own drummers – and, by some miracle, found people who savored that eccentricity.

Music needs these oddball outsized personalities right now. To breakup the monotony of conformity. To challenge the safety of orthodoxy. To suggest other ways of thinking about song, sound, texture. To push at (if not stomp on) the confines of the grid.

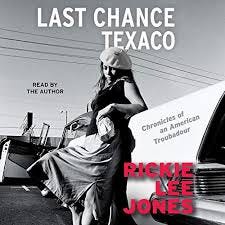

This thought has become a frequent presence lately, running in the background between the paragraphs of Last Chance Texaco, Rickie Lee Jones’ striking memoir.

Jones is another of these criminally underappreciated high-wattage types. A character. A survivor. A tempestuous chameleon who changes the vibe in a room with a sigh, or a sideways glance – and then thrives on the resulting squirm.

Jones gets tagged a singer-songwriter, and that’s probably the closest description of her work. But it’s woefully inadequate. Where so many singer-songwriters organize their songmaking around the stepwise business of narrative, she strives for more filmic sensory evocations – bohemian streetcorner scenes rolling into vast desert vistas or uncomfortably rowdy skid-row bars. Hers is a rush that involves words and stories-in-progress (yes, of course), but they’re enmeshed in a sonic stew of overlapping voices and troubadour guitars. And haunting high-register voices that streak across the soundscape like cars Dopplering past on a highway.

I didn’t have high expectations for Last Chance Texaco. The latter-day rock memoir has become a thinly disguised ego exercise, with lurid details covering for an absence of reflection. Jones renders the key stories of her formative years in clear prose, but she doesn’t stop there: She brings readers into the effect those events had on her then, and have on her still. She’s good at context. She leans into the stories that left a lingering impression or taught her something. She finds the poetry within pained outsider adolescence – and as she does in song, she toggles from big picture to closeup, spotlighting some details and glancing at others in ways that often made me want to hear the stories again.

Jones counters the usual rockstar fatuousness with sometimes brutal self-deprecating honesty: She spares little when talking about the escapades of her young adult life – at times you can feel her shaking her head. But then she’ll turn around and share the galvanic effect of hearing, for one example, Laura Nyro’s New York Tendaberry: “This record made me not only want to be a part of her world, but to think I could make a world of my own. I recognized her, I recognized myself in her.”

Spurred by that perception and others like it, Jones moved at warp speed to cultivate a sound; by the time she made her recording debut, she was a stone cold original. She’d developed a phrasing approach that had the swing and flexibility of the great jazz divas and the truth-telling bluntness of Mose Allison but sounded like neither. She told about tense confrontations in the language of West Side Story showdowns, then wrapped her stories in wondrous and occasionally fantastical imagery, then surrounded them with ear-stretching and unconventional chords. She pulled from all over the past but by the time she was through, she’d worked the references into something that was completely her own thing.

Reading Last Chance Texaco, you might not get a step by step recipe for creating this kind of sonic identity. But you will know this much: To do what she did, you pretty much have to start out as a character.

I have always, always been a huge fan of Rickie Lee Jones. She's an original, most definitely. One thing I would mention in addition to this terrific essay is that she had an easy relationship with male instrumentalists that very few singers enjoy. They respected her and her vision...and fun was had by all.