Legacies In Progress

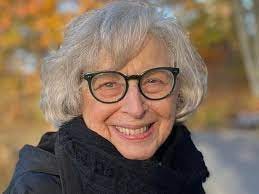

On the unexpectedly deep return of Dorothy Moscowitz

There’s real art to the “Recommended If You Like….”descriptions that accompany releases on Bandcamp and other platforms. The task is a kind of shorthand enchantment – to throw together a seemingly random cast of artists and sounds that allows the reader to get a general idea of the tilt of the work in question. These can seem determinedly weird, or provocative, or preposterous.

Here's the list of triangulation points used to describe the beguiling Under an Endless Sky, the latest work featuring vocalist and sonic renegade Dorothy Moskowitz: “Late-stage Marianne Faithfull, Mercury Rev, Terry Riley, Flaming Lips, Italian electronic music, The United States of America, Leonard Cohen's 'You Want It Darker.'”

OK, that’s pretty much a Must Listen. Just because of that wry juxtaposition of Mercury Rev and Cohen’s exquisitely dire “You Want It Darker,” and for the delicious brand-name salad that deftly links Moskowitz, who in the late ‘60s was a key part of the proto-psychedelic rock band The United States of America, to more contemporary artists influenced by her band’s sprawling avant-psychedelia.

Though her most famous album was the United States’ classic debut (also the band’s swan song) in 1968, Moscowitz, who is in her ‘80s, has been involved in some formidable work; she was long a part of Country Joe McDonald’s All Star band, recorded a series of experimental South Indian ragas for Folkways, and has appeared on Sesame Street. The delicate, intimately experimental United States of Alchemy finds her collaborating with Francesco Paolo Paladino, an avant-garde Italian composer known for scores that blend techniques of electronic ambient music with orchestral instrumental colors. Lyrics were mostly written by Italian writer Luca Chino Ferrari in collaboration with Moscowitz; they address grief and loss and the vanishing natural world (one mesmeric piece is called “The Disappearance of Fireflies”) through inflection, repetition and slight poetic changes to syllabic rhythm.

Under an Endless Sky places Moscowitz’ clear, resolute voice in the middle of ear-stretching tapestries: “Cut the Roots Pt. 2” is a symphony of bells, chimes and metallic percussion, while the 24-minute title track sends a percolating organ figure into the forefront and then the background of a vast chordal drone. This lush setting is the way the album opens, and it sets the tone for all that follows – its sense of calm carries through the sentimental grieving songs and the thoughtful laments about the damaged state of the environment and its inhabitants (the only slightly over-the-top “My Doomsday Serenade”).

The improbable return of Dorothy Moscowitz hit me in a profound way. Not just because the record is so thoroughly absorbing, or because it’s the inspiring story of a woman in her ‘80s making brilliant use of her talent – but because for decades now, her legacy has been fixed. She’s typically referred to as the singer in The United States of America, the wacky short-lived art band that foreshadowed our screen-centered malaise via lyrics like “The cost of one admission is your mind.” Now, those little capsule biographies that bounce all around the Internet will need to be rewritten, expanded to include this low-key soul-piercing collaboration.

This return underscores how the very notion of “legacy” is changing, becoming more fluid. Every link in the chain, every archival discovery has the potential to not only expand an artist’s profile, but shift the commonly circulated narrative of said artist’s contribution. A single overlooked title can do it; a trove of live recordings can, too.

Case in point: After the saxophonist and composer Wayne Shorter died a few weeks back, the jazz Internet was ablaze with awestruck comments about records or individual solos that deserve further attention. A friend recommended me to the 2001 Miles Davis release It’s About That Time, which captures Shorter’s blistering work on March 7, 1970 at the Fillmore East in New York. This is the last recording of Shorter with Davis’ group – which featured Chick Corea on bracingly distorted electric piano, bassist Dave Holland, drummer Jack DeJohnette, and percussionist Airto.

It’s the moment just before Shorter teamed up with Joe Zawinul in Weather Report, and it captures the Miles electric-band concept at a thrilling, mind-melting energy level. The material includes songs from Bitches Brew, which was released just weeks later; the group operates at whiplashing intensity, as though they’ve been tearing apart these tunes for years. Of particular note is the intuitive communication between Shorter and Corea: On “Directions,” “Spanish Key” and others, the saxophonist generates skittering high-degree-of-difficulty lines and grid-busting squalls that challenge – and frequently disrupt -- Corea’s frameworks. Their conversation becomes a series of cycles, with fleeting expressions of order evolving into frantic and defiant leaps into total musical freedom. This night might not be a career highlight for Shorter (there are so so many) but it offers perspective on a pivotal moment in his evolution. Shorter might sound a teeny bit reserved on Davis’ electric studio forays but by March 7, 1970, he’d figured out exactly how he wanted to engage, if not steer, the conversation.

I Go To The Rock, the latest compilation from Whitney Houston, could have been a career highlight: It’s devoted to her gospel recordings, gathering material from various film soundtracks (including, most obviously, The Preacher’s Wife) as well as live performances and several previously unreleased tracks recorded when she was 17.

The early material catches Houston pre-stardom, at a time when she was just beginning to attract attention beyond the church community of Newark, New Jersey. These songs are straightforward, perfunctory demos jolted alive by her riveting vocals; the uptempo “Testimony” shows her assured, riveting, rhythmically astute phrasing years before she became pop music’s reigning master of melisma. Houston laced pretty much every phrase with emotion, sometimes too much emotion. Still, her performances of gospel standards have a way of humanizing glossy tracks that carry the telltale early ‘90s time-stamp: “Hold On, Help Is On the Way,” one of several tunes with the Georgia Mass Choir, demonstrates how Houston used spontaneous vocal ad-libs to transcend the slick, sometimes almost suffocating studio productions. She was a force, and this hodge-podge compilation doesn’t show that more consistently. Missed opportunity.

Yes, we have a digital suggestion box. Share underloved/overlooked records, artists, performance practices, etc. at echolocatormusic@gmail.com.

Hey Tom. I thought you might get a kick out of this interview I did with Dorothy M and United States of America mastermind, Joseph Byrd. https://we.tl/t-TABu85Pqhg

Love this and shared it with our musicians. We used to be a neighbor of Terry Riley. Quite the human being!