The Hot Take Marketplace has plenty of fancy explanations for the success of Khruangbin, the Houston, TX trio that specializes in an original, mostly instrumental form of languid, dub-inflected global groove music. The sound is open, uncomplicated; it communicates first to the hips, and has little use for the spasms of technical whiplash associated with latter-day jazz fusion. The trio routinely sells out arenas and large halls (a terrific 2023 live record was captured at the Sydney Opera House); its psychedelic visuals and booming bass-forward sound have made it one of the most solid, reliable acts in an increasingly unpredictable live music environment.

Some culture-studies people explain Khruangbin as a kind of palliative for stress – “zone out music” for overtaxed minds. (This assessment is not wrong.) Critics, not content with something so obvious, invoke post-modern jargon and tortured genre recipes to pierce the Khruangbin mystique (it’s “Thai funk cut with ranchero lilt as mixed by Lee Scratch Perry”).

What if the reason to pay attention to Khruangbin is less nerdy/theoretical? What if it’s about the thing that’s happened in popular music forever, involving a few musicians in a room exploring how far they can travel while working out on a single groove? What if it’s just “Plays Well With Others?”

This is not an exotic ideal. Not a novelty. And it should not be a rare or endangered thing. It is a foundational element that runs through all kinds of backbeat music, part of the unseen/offstage development that led to so many formidable rhythm sections – in Muscle Shoals and Memphis and Macon, Philadelphia and Detroit and Chicago and countless other regional hotbeds.

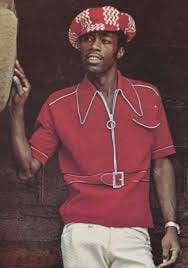

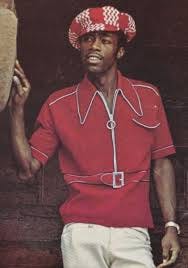

When I first encountered Eddy Senay, the Detroit-based guitarist and composer who made two sparkling and austere instrumental records for Sussex (the label then headed by Clarence Avant) in 1972, Khruangbin came to mind right away. There’s sonic kinship – they share a love for guitars that can sting or sound fuzzy and psychedelic, and like Khruangbin, Senay’s rhythm section understands how to stay home and cover the basics, respecting every partial of an undulating groove. This is audible on the startlingly low-key opening track of Senay’s debut, the aptly named “Just Feeling It.” (Oh for the days when something this vibey and downtempo could be a Track 1….)

To 2025 ears accustomed to music with a high dazzle quotient and a crowded event horizon, Senay’s music might seem, initially, to be a bit too laid back. For long stretches, it’s just a bedroom-soul groove – built on a simple drum pattern, a complementary conga pattern (from Eddie 'Bongo' Brown, a member of the famed Funk Brothers crew), a bassline that repeats but is slyly changed up occasionally, and terse accompaniment riffs from keys and a second guitar. The individual parts are intentionally unexceptional. They are an aesthetic choice. They reflect the understanding, shared by all participants, that one way to cultivate and sustain a long-distance groove is to keep some lanes open and a portion of the bandwidth clear. So that the players can emphasize the hypnotic possibilities of the pattern out beyond the notes. So that they can lean meaningfully into some phrases, creating a kind of “punctuation” that ever so gently adds heat.

It's an approach to rhythm section minimalism Khruangbin does brilliantly. Check the vibrant yet understated rendition of “Pelota” from Sydney.

In promotional material touting the 2017-2019 reissue of Senay’s limited catalog, the guitarist describes his intention for his music this way: “We didn't want to be too technical or overly fancy. We want to keep it simple, funky and plain. We don't want to overdress it, we don't want too many horns, too many strings or too many keyboards. We want to keep it as raw as we possibly can get it.”

Senay pursued that notion throughout both of these records, on proto-funk originals like “Cameo,” (sampled by Pete Rock & C.L. Smooth on “Act Like You Know”) and chill groovers like “Delgado,” which features a crisply articulated melody featuring Senay on his Hagstrom guitar and Rudy Robinson on Wurlitzer electric piano. Senay’s melodic instincts shine on his covers – of Donny Hathaway’s “Zambezi” and a stark, haunting version of (then-labelmate) Bill Withers’ “Ain’t No Sunshine.”

In the music world of 1972, these Eddy Senay records were not curiosities or outliers; this kind of unified playing, this sensitive and selfless groovetending, was everywhere. On records by Funkadelic, and Curtis Mayfield, and Stevie Wonder and on and on. Regardless of the messages of the songs, the implicit message coming through the grooves was one of cohesion. People working together, in real time, to create something that just felt good. Khruangbin is part of that tradition. And they’re not outliers either.

Just love this-back to the 70s! Truly groovy. Thanks Tom!