Preparing for a talk on “Thriller at 40” this Thursday at Camden County College (info here for those in the Philadelphia area), I recently spent an unexpectedly engrossing few hours with Michael Jackson’s 1982 megahit. On headphones. Cranked loud. With no visuals. (Not even the video in the link above….I’m using it to get the right audio.)

It had been awhile since I’d visited Thriller -- probably true for many who found his off-stage behavior deplorable and abhorrent, and were further repelled by the river of ugly revelations that surfaced after his 2009 death.

And there’s this: For decades now, many of us have had no choice at all about how or where we’re bombarded with this album’s many hits. We have deep sense memories created by repeated exposure, from soaking them in at sports events or in bars over and over again. We know the routes these songs take – the grooves and the breakdowns and the vocal cackles, the exact syllabic scheme of that “mama-seh” earworm from “Wanna Be Startin’ Something.”

There’s a world beyond those inescapable elements, and much of it has producer Quincy Jones’ fingerprints on it. Listening at close range, it’s possible to geek out on the smallest of details – elements of the composition, or the arrangement, or the performance that we maybe don’t even notice most of the time.

When I encounter one of these aspects of craft, I think about it in terms of decision making: Why does this sound drop in out of nowhere right here? What is gained by pushing the percussion to the forefront of the mix for these few measures? Jones, a grand master of the granular, is intentional about every last echo in his productions.

Gazillions of those types of decisions go into a pop record like Thriller. Each addresses a specific objective, and over time these decisions accrue into the “identity” of a track. One flyspeck example: The second verse of “Billie Jean.” Within the first 90 seconds, we’ve got the basic narrative and have experienced the cautionary tale of the pre-chorus and the instantly grabby rhythmic cadence of the chorus. At 1:50, Jackson starts verse two with the phrase “For forty days and for forty nights…” On the downbeat of that entrance, we hear a small string ensemble (just cellos?) playing a long tone in unison. It lurks somewhere in the middle ground of the mix but it’s inescapable, and as the verse continues, the strings play a slight soap-opera-style melody before returning to the sustained single note. The effect is striking: Up front Jackson sings in fitful emotional knots; meanwhile the strings sail forth on serene seas.

That trick – with strings starting on the downbeat right with the vocal and then sustaining – has been around awhile; Nelson Riddle used it on Sinatra records. It creates a low-key, almost imperceptible tension, and after I focused in on it, it became easy to lock onto the variety of tactics within the string arrangement – the stabs that outline the signature syncopation of the tune, the tiny micro-crescendos that usher in the chorus, the shivering descending phrase that punctuates the takeaway phrase “Just remember to always think twice.”

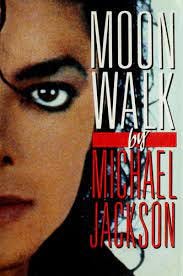

In his memoir Moonwalk, Jackson recalls writing the tune. "A musician knows hit material. It has to feel right. Everything has to feel in place. It fulfills you and it makes you feel good. You know it when you hear it. That's how I felt about 'Billie Jean.’”

He’s talking about the entirety of the track, of course. Nonetheless, Jerry Hey’s wondrous string arrangement plays a crucial, if underappreciated, role in that. Dialing into just that single aspect of the work is to be reminded about the little things — those squibs that are obsessed over in studio control rooms and lost on most listeners. They enhance the whole. Arguably make the whole. That’s the thing about a meticulous production like Thriller: It’s possible to savor it from countless different angles, following only what the guitars are doing, or when the bassline changes, and so on, track by track, until you hear the whole thing differently.

Yes, we have a digital suggestion box. Please share your favorite overlooked/underloved records at: echolocatormusic@gmail.com.

The only thing that would get me to listen to Michael Jackson again is commentary as intelligent as this is. Thanks, Tom.

Lots and lots of production on that album. I remember when it came out. The dance (in a parking garage?) reminded me of the scene in the first film West Side Story when Riff is dead and the Jets congregate in a warehouse and dance and sing to Cool. I loved it. When Jackson turned into a monster, it scared my youngest so badly. But he still wanted MIchael's glove for Xmas!