It's All Details

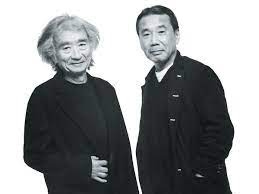

Lively dialogs between Seiji Ozawa and Haruki Murakami suggest an approach to (and maybe even a philosophy of) listening

Early in the fourth movement of Brahms’ Symphony No. 1, there’s an exposed theme statement for French horn. It sounds like a single instrument, but it’s actually written for two players. As conductor Seiji Ozawa explains to the novelist Haruki Murakami in one of the extended conversations that make up the transfixing Absolutely On Music, the idea is that the two instruments play the same thing in alternate measures, overlapping slightly. “Brahms specifies these small details so the audience won’t hear the instrumentalists taking a breath.”

For most listeners, this slight, perhaps trifling consideration doesn’t factor into appreciation of the piece. It’s a detail, one among thousands that go into a symphonic work; Brahms wanted an unbroken line, and figured out how to get it. Because hey, the sustain pedal had not yet been invented when he was actively composing.

The passage underscores one of the recurring sermons within this remarkable little book: It’s all details. All of music, the essence of it as experience and phenomena, is rooted within tiny considerations that can be, and often are, overlooked. Blown right past on the way to the candy-coated hook. Talking geek details: The breath control necessary to conjure the unbroken French horn line is nothing like the breath control Miles Davis used to express infinite crinkled nuances through the muted trumpet. Which is not the same breath control that a piano soloist employs when drifting away from the orchestra to freely interpret a cadenza.

As Ozawa and Murakami discuss the 2010 live at Carnegie Hall recording of the Brahms, we learn that the performance had been edited in post-production to clean up extraneous noise, as well as to rebalance sections of the orchestra – a common occurrence in digital-era classical recording. Prompted by Murakami, Ozawa observes the singular phrasing of several soloists, then pivots from micro to macro to note the enhancements made to the overall sound of Carnegie Hall he’s observed over decades of music-making within its storied walls. Ozawa drops a bonbon about some aspect of the piece or the orchestra that’s playing it – the Saito Kinen orchestra he helped organize as a part-time festival group in 1984 – and Murakami is there with a return volley or alert followup query that triggers more discussion, or a dive into a different body of water.

Absolutely On Music captures the bounding, endlessly animated thoughts of Ozawa and Murakami as they listen to specific pieces of music – or, frequently, different performances of the same piece. Drawing on Murakami’s extensive collection of vinyl and CDs (there’s an excellent playlist on the author’s website here), the two compare various renditions of Brahms’ Piano Concerto No. 1, including a famous live one in which New York Philharmonic conductor Leonard Bernstein issued a disclaimer from the podium about pianist Glenn Gould’s unorthodox interpretation. The recorded version they’re hearing includes the speech, which Murakami transcribes for readers, and when the music begins, Ozawa, then an assistant conductor under Bernstein, recalls being there and not understanding all of the English – but enough to disagree with Bernstein’s decision to say anything. “At the time I felt that saying something like this before a performance was not the right thing to do. I still feel that way.”

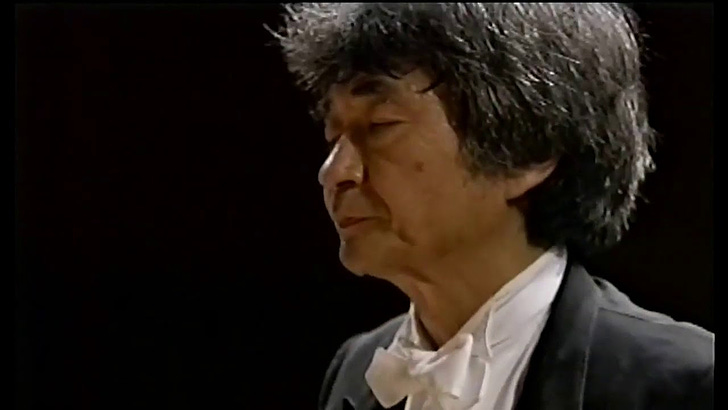

The dialogs derive richness from differing orientations. Murakami explains early on that he has no musical skill; he’s just a listener whose understanding has been shaped by (among other things) noticing things at an almost microscopic level – the same exact discipline he employs as a writer. Meanwhile Ozawa is a name-brand expert, a world renowned conductor who served as the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s music director for 29 years. As they trade observations and reactions, the difference in education and experience simply dissolves, and the dynamic becomes one of shared inquiry, the kind that doesn’t require specialized knowledge nearly as much as it requires focused attention, and fundamental curiosity.

At one point Murakami asks Ozawa about the difficulties of retaining the structural details of a Mahler symphony (as opposed to one by Beethoven or Brahms), asking “Is it possible for a conductor to fit the entire complex construction of a Mahler piece inside his head?”

Ozawa’s “answer” to that excellent question stretches over several pages of general ideas, followed by an incredible nugget from his training. He was once invited to his professor’s house with another student, composer Naozumi Yamamoto. The revered professor Saito gave each student blank score paper and told them to write the score of Beethoven’s Second Symphony – from memory. The idea was to see how much of the music the students could notate from memory, in an hour. “Sometimes I’m knocked out before I can write twenty measures,” Ozawa confesses, lamenting that he struggled to write the viola and second violin parts correctly.

It's a paradox: When explored at depth, seemingly insignificant details light up the far corners of a piece of music to supercharge our awareness and lure us into still-deeper engagement. Meanwhile out in the world, we are drowning in details. We suffer from spec-sheet paralysis. We drill down indiscriminately, agonizing over distinctions that turn out to be distractions.

The trick, of course, is to seize on the details that matter. It can be incredibly challenging to do that with art – everyone has their own notion of what a masterpiece is, after all. Ozawa and Murakami are not acting as teachers here, but there are lessons within their thoughtful rapidfire volleys. If a life goal is to become more intentional about savoring the details of music, Absolutely On Music is a must.