Incoming for RSD: A Megadose of Ahmad Jamal

On Record Store Day, a chat with Zev Feldman about his new Jazz Detective imprint

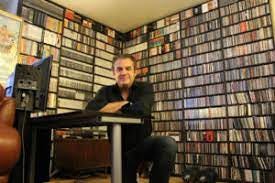

Just about every year since Record Store Day began in 2008, the vast unreleased offerings have included at least one rarity discovered and prepared for release by Zev Feldman. A longtime veteran of the music industry, Feldman opened up a new lane for old and neglected music, by aligning with small boutique labels (Resonance, Elemental) to make high-quality limited edition vinyl for RSD. (Weeks after the initial run, the material becomes available widely, via CD and via streaming.)

These crisply mastered packages, each featuring beautiful photographs and carefully researched liner notes, are culled mostly from live performances but have included occasional studio sessions – and feature historically significant performances by guitarist Wes Montgomery, pianist Bill Evans and others.

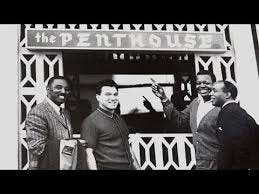

For this year’s Record Store Day (it’s today! the Super-Mega Black Friday Edition!), Feldman brings out two sparkling live documents from legendary pianist Ahmad Jamal. Recorded for radio broadcast over KING radio at the Penthouse club in Seattle, these double-LP sets capture Jamal during multiple engagements, with different accompanying musicians: Emerald City Nights: Live at the Penthouse (1963-1964) and (1965-1966) arrive today; a third, devoted to performances from 1966-1968, will arrive next year.

The inaugural releases for Feldman’s newest label venture Jazz Detective, these fill in an important slice of Jamal history. By 1963 the pianist and composer was well-known: He’d had a huge jukebox hit with “Poinciana” from the 1958 Live at the Pershing, and built on it through subsequent releases. The success enabled him to work on his own terms, and for a while he stepped away from performance entirely, doing studio recordings while working as an investor and (briefly) a clubowner in Chicago.

But as the Pershing album and his many other live documents (check the 1962 Live at the Blackhawk!) demonstrate, Jamal’s art blossoms most ravishingly in live performance. He gradually returned to touring in 1963, selecting rooms where he felt comfortable like the Penthouse – which was outfitted with a nice piano and a mobile-recording rig. (Several of Feldman’s other releases have drawn from the club’s large archive of performances.)

Emerald City Nights catches Jamal during an important and under-documented step in his evolution: He’s still got the lighthearted, dancing optimism that marked his late ‘50s style, but is exploring ways to balance that exuberance against thicker, stormier harmonic progressions. He starts with the instantly relatable grooves of his “Poinciana” days, and then slips harmonic challenges into the margins, creating a sound that’s at once classic and sleekly modern. Jamal sounds like he can go anywhere: He adds knotty, ear-stretching dissonances to conventional jazz standards, completely overhauls the harmonic frameworks of tunes like “Who Can I Turn To?,” and injects whimsical quotes into his block-chorded shout choruses and scampering, lighthearted lines. (Check the extended Sound of Music fantasia within his “Like Someone In Love.”)

Each element of Jamal’s trio is rendered perfectly: Where some archive live performance discoveries can be shrill or sonically taxing after a few minutes, the audio of Emerald City Nights is pleasantly open. Relaxed, just like the music. We’re hearing essentially what Jamal and his collaborators heard on the stage.

In a recent interview, I asked Feldman about his first reaction when he heard the raw tapes that became Emerald City Nights.

Q: Were you surprised by the audio quality?

A: I have two huge Rubbermaid tubs of tapes from the Penthouse, and most of them are solid, they’re broadcast quality. They’re engineered and recorded brilliantly, in mono. What first captivated me about this was all the dynamic contrasts, how the room gets quiet and all that….Pretty soon into listening, it became clear that this was one of those iconic things like Miles Davis Quintet Live at the Plugged Nickel, where we are incredibly lucky to have this music. You can just put these on and listen side after side, there’s nothing in the way. The music from him will seep into your pores. If you want to get into the Ahmad Jamal time machine, we have the coordinates all set. Just put the record on.

Q: With many of these discoveries, you’re dealing with the estates of musicians who’ve been gone for decades. But Ahmad Jamal is very much alive, and making incredible music. Was he involved with this?

A: Mr. Jamal supervised every aspect. We knew at the start that he is very selective. So we got copies of the music for him to listen to, and pretty soon he reached out to say how excited he was to hear these recordings, 60 years later….He selected the performances, sequenced the songs, approved everything. Which was a thrill for me.

Q: Myself and other media cynics sometimes think that archive labels are happy to release anything from a name-brand artist, regardless of the level of the art. I sense that you think about these projects as historical documents — that you’re careful to be a “guardian” of sorts of the artist’s legacy.

A: I think people are human. Usually the tape is really good, and speaks to the genius of the artist. But there are off nights, everyone has them. And I think about that all the time — if we’re going to expand the discography of an artist, the [new discovery] has to add to the legacy in a substanial way….Sometimes you’re all excited because someone gives you a rare tape, and my reaction is strongly that if he was alive, he wouldn’t want this to come out.

Q: And you’ve probably been inundated with material in recent years….

A: I consider myself incredibly fortunate every time, too. We do get people who are just sure they’re going to retire on some rare recording from 50 years ago — part of my work involves explaining how expensive it is to go from raw tape to a finished product. There’s all the audio work, and then the licensing, then researching the circumstances of the date, finding photographs from the period, figuring out the best way to tell the story of the recording, and after all that, the marketing and publicity. It’s a little like building a pizza, an expensive one, and each aspect is important…..I’m an old-school record store person, I believe in the power of holding a record in your hand, and I love it when that record documents a bit of history. [But] as business we have to be careful about investing in recordings that will recoup the initial outlay. Just one of these projects costs enough money to hemmorage a company.

Q: It seems like Record Store Day has become integral to these limited-edition projects.

A: I just love everything about Record Store Day. For me, it’s a way to get music to people, and to get people excited about music. It was never about being greedy, or a long-tail situation where we’re superserving an elite audience — it was and is about can we share these rare recordings in a way that honors the work, the artists? Because as the years roll by, the decades roll by, what these artists did becomes more valuable. I mean, music and artistry is an emotional good. It’s a positive thing in this crazy world. I want people to encounter them and get all the feels from them.

👍