You know what we should hang onto?

The sound of three or four or six people singing together. In real time. Harmonizing (or not). Expanding a single-note melody line into something else. Arriving at a sonic creation none of them could have conjured alone.

You know…..something like this:

Or this:

What these performances share is a sound of unity, a coming together that both involves – and transcends – notes and pitches. This type of singing demands that the individuals attend to their own parts while also addressing the overall contours, braiding themselves into swerving constellations of sound. The vocal blend sounds entirely natural but is never an accident; it’s a unique-to-the-moment sonority that is the product of skill, high alertness and innate musicianship.

It’s also quite possibly on the way to being a lost art. I’m talking here about performances – not elaborate Digital Audio Workstation accomplishments, those pileups of multi-tracked vocal stems that Justin Timberlake and John Legend (and, even more floridly, Jacob Collier) assemble into high-rise towers of singing sleekness.

The studio techniques that assist current artists are deeply entrenched and expanding constantly (see Auto-Tune, the famous software plug-in, and its many offshoots). They’re here to stay. They save time. They facilitate rapid “let’s-try-this” experimentation. And they’ve led to amazing music, no question.

Still, maybe it’s time to think a bit about the tradeoffs, what’s lost with that approach. Just about everything governing the modern task of recording vocals – the specific harmonies used, the plush uniformity of the multi-tracked voices, the density and on and on – cuts out the core vocal blend. What the singers in doo-wop harmony groups and rock bands did naturally, standing next to each other, went beyond the assigned notes: They balanced their individual tonal characteristics, gathered contrasting elements (like sour against sweet) into a singular entity. From disparate parts, they found an unassailable tonal power. And beauty.

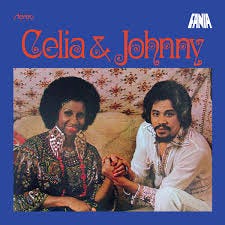

I was thinking about this the other day, listening to “Quimbara” from the iconic 1974 collaboration between Celia Cruz and Johnny Pacheco. It’s a blast of rarified energy that’s got all the hallmarks of the Fania Records hit machine; as a result, the song and album were mentioned in many appreciations of the Fania co-founder Pacheco, who died February 15 at age 85. The pieces talked about Pacheco’s knack for creating instantly memorable hooks and his contributions on multiple instruments (flute and percussion) and also his considerable business acumen. He was described, accurately, as not just a titan of Latin music but a titan of modern music, one of those who, in bringing New York’s driving salsa to the masses, elevated dance rhythms to a place of high art.

Curiously, not many of the tributes mentioned a crucial aspect of Pacheco’s record-making: His mastery of the call-and-response exchanges between lead singers and the “coro,” the three-and-four part vocal backgrounds. In these volleys, the team of background singers use a recurring phrase to goad or inspire the lead singer, who responds by ad-libbing. These exchanges are part of Latin music going back decades; Pacheco, who grew up in the Dominican Republic before moving to New York, would have heard them on records by the Cuban group Sonora Matancera, which helped launch Celia Cruz, and others as a kid.

Even Pacheco’s earliest recordings show deep understanding of the sparkplug energy of the call-and-response, and the ways to enhance it with a distinctive blend. Pacheco understood the coro as a call, an appeal; to put its messages across, he assembled contrasting vocal types and highlighted the differences. He situated his nasal falsetto tone, which was naturally strident and ear-catching, within an array of more pleasant tones, from the husky (Adelberto Santiago) to the sweetly mellow (Justo Betancourt, Ramon Rodriguez). When repeating a percussive phrase like the one on “Quimbara,” the singers of the Fania coro sounded less like the suave Miracles and more like a relentless rhythm machine, as important to guiding the pulse as the conga drum.

You can hear this signature approach to coro singing on literally hundreds of Fania titles, involving different combinations of voices. One of them is this gem from Willie Colon recorded in 1973 with the legendary lead singer Hector Lavoe.

And of course there are examples of similarly rousing blends from all corners of the globe – check this interesting recently reissued work from Ghana’s highlife band Vis-A-Vis, recorded in the 1970s….It features a small team of singers, moving deftly together as though dancing.

That blend, all these blends, are the product of more than just technical skill. While the coordination of pitch and timbre and phrasing are part of the equation, the ear first picks up on something more elemental – the vibe, the feeling, the attitude. Working together, these vocalists cut through the air to impart an instant uplift. They show us what the diversity of textures and sounds can do, and what can happen when people work together, in real time, toward harmony. This isn’t a lost art – yet. But it’s another of these performance practices that’s under stealth threat from technology, and it won’t travel to future generations unless we teach it, savor it, celebrate it.

Yes, we have a fancy digital suggestion box. Share your favorite Underloved/Overlooked records here: echolocatormusic@gmail.com.

Please consider subscribing (it’s free!). And…..please spread the word! (This only works via word of mouth!)