In His Presence, Strata Searching

On the magical record Charles (Charlie) Rouse made for Strata-East

Charlie Rouse’s “In His Presence Searching” opens with simple elements – an arpeggio-like electric cello figure set against carefully plucked repeated guitar chords. Rattling percussion, from Airto Moreira, enhances the faint aura of ceremony. Rouse’s tenor offers a simple prayerlike melody that repeats twice. Then things slow to a clearing pause. When the music resumes, the cello elaborates on the theme and Rouse, now on bass clarinet, adds trills to thicken the harmony.

Before it is anything else, before the brain can even classify it as “jazz,” this piece captivates through the resonance of its textures. The sounds, individually and when conjoined, suggest something a bit unusual, exotic – the long release time of the electric cello brushing against guitar operates as a kind of sitar matrix or a natural drone, enveloping everything else. Rouse’s warm, untroubled tenor slides effortlessly into this environment, and as happened on so many records by Thelonious Monk, he carves out his space without demanding any fancy lighting.

The extended intro of “In His Presence Searching” doesn’t develop over time into some billowing tones-of-peace mantra: It’s disarmingly deep from the very first notes. That’s because of the sensitivity of the musicians, who instantly establish a basis of communication — a way of walking through this unusual textural environment while preserving (honoring?) its spaciousness.

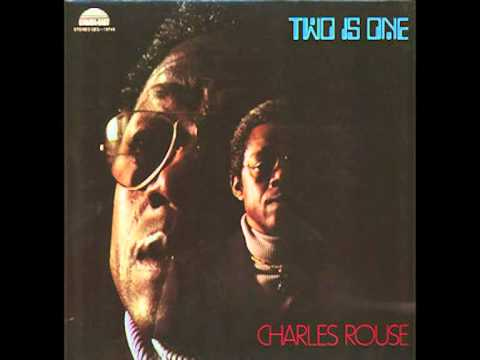

After this transfixing, world-culture-classic intro, “In His Presence Searching” evolves into a groove. It’s the last track on Two Is One, Rouse’s 1974 album for Strata-East Records, the artist-run collective that was formed in 1971 by trumpet player Charles Tolliver and pianist Stanley Cowell. Strata-East occupies a unique place in the history of improvised music; it documented some of the most visceral, groundbreaking creative black music of its era, including the Gil-Scott Heron and Brian Jackson Winter In America and other socially conscious works aligned with the Black Arts Movement. Its titles, many of which were pressed in small numbers, have been pursued by DJs and collectors for decades — in part because each record evolves from and celebrates the unique communicative ethos of the musicians involved. (Jazz Times has an informative oral history of Strata-East here.)

This month, the jazz label Mack Avenue is returning the Strata-East catalog to circulation. Mack Avenue has hired A-list audio wizards (Kevin Gray of Cohearent Audio) to restore the audio, and jazz historians (Syd Schwartz) to recontextualize the label’s contribution and influence. Next week brings an anthology, Strata-East: The Legacy Begins, followed in early April by a vinyl reissue of Pharoah Sanders’ Izipho Zam (My Gifts). On April 25, Strata-East will reissue (on vinyl and CD) Rouse’s Two Is One, Charles Tolliver’s Music Inc.’s Live at Slugs’, Vol. I & II, and Stanley Cowell’s magnificent solo piano date Musa: Ancestral Streams, the latter discussed here.

[This evening, at 6 PM EST, there’s a livestream roundtable featuring Nate Chinen and other critics talking Strata-East. To register, click here.]

It’s unclear if the reissue project will eventually cover all 50-plus Strata-East titles, but here’s hoping it at least includes the 1972 live album by the percussionist Mtume, Alkebu-Lan – Land Of The Blacks, which features Cowell, violinist Leroy Jenkins, saxophonists Gary Bartz and Carlos Garnett, vocalist Andy Bey and drummer Billy Hart. Mtume assembled his 15-piece large Umoja Ensemble while working in Miles Davis’ group; its simmering rhythms, bracingly thematic solos (listen up whenever Cowell starts to dig in…) and expansive, roaring, coloristic sound capture a (fleeting) moment when improvising artists were exploring new ways to balance freedom with structure. It’s among the early records that embody Strata-East’s bold, uncompromising aesthetic.

Aside from the rousing introduction discussed above, Rouse’s Two Is One has different aims. It falls somewhat short of Mtume’s aesthetic beacon, dwelling in an agreeable low-pressure rhythmic zone centered around funk and cannily chopped-up straight-8th pulses – grooves that were everywhere in 1974. To those who’d been following Rouse during the 11 years he spent as a sideman with Monk (from 1959-1970), these streamlined tunes might have seemed like a facile downshift, a crossover move.

Rouse, though, is the same crafty improvisor he was on such enduring records as Monk’s Dream (1963). He deploys the short phrases and pinpoint articulations that routinely coaxed Monk to get up from the piano and dance; his more elaborate lines on “Hopscotch” (which features Stanley Clarke on bass) weave between consonant and dissonant tonal centers with more playful spirit than revolutionary intent.

It's been said that Rouse was temperamentally suited to the role of sideman to a towering figure like Monk. Part of that is simply innate musicality: The saxophonist knew, on an innate level, the roots of Monk’s music and the punctuation the pianist used to put it across. He respected the details of tunes like “Evidence,” and understood that when it was time to solo, he didn’t have to be as whimsical or as intervallically daring as Monk. He just had to express his ideas with rhythmic clarity, and imbue them with the syntax Monk used as a composer, if not outright echoes of the idiosyncratic melodies. More fiery tenor players worked with Monk – see Johnny Griffin, John Coltrane – but none caught the essence of Monk so completely.

Just before he joined Monk, Rouse made a record for Blue Note called Bossa Nova Bacchanal (issued in 1962). Though it looks like another of the many jazz titles that followed the Stan Getz/Joao Gilberto collaboration, it only features one frequently recorded hit (“Samba de Orfeu”) and travels away from samba and into son and Afro-Caribbean rhythms with a kind of blithe exuberance.

Bacchanal and Two Is One, bookends to Rouse’s Monk adventure, share key traits: They’re smart without being cerebral, and attentive to the ever-multiplying possibilities that originate in riff-making rhythm, a la Monk. They also have a common openness, a sense of welcome — the lyrical melodies and textural accompaniments invite listeners into the searching in progress, and make it seem like vital work.

Here’s a curious thing you might discover by listening in a loose chronology that begins with Bacchanal, touches down on Rouse’s early work with Monk (the 2018 release of music from the film Les liaisons dangereuses 1960) and then takes in Monk’s Dream and maybe a live record from the mid-’60s (Live at the It Club, 1964) and ends with Two Is One: Rouse doesn’t seem to evolve according to the standard jazz narrative. His improvisations grow more nimble as he assimilates Monk’s ideas, but throughout this span, his identity, his voice, doesn’t change. He sidesteps stock bebop jargon on the bossa nova project, sidesteps it some more in the early days with Monk, and he’s still resisting it on Strata-East. Rouse brings a keen situational awareness to each setting. He doesn’t retrofit his Monk tricks for Two Is One; even when he uses the snapped-off phrasing and rhythmic displacement associated with his Monk recordings, those devices sound new, as though developed to align with the Two Is One ethos.

Rouse might not have been a tenor titan, but he was a musical titan, operating at his own pace. His lone Strata-East title was — and still is — a gateway drug to the harder stuff that became the label’s specialty, as the guitarist Jeff Parker recently wrote: “This album introduced me to Strata-East Records, and I've been... following the label and collecting the records ever since."

Great piece, Tom. I admire Rouse's playing with Monk and have always loved the bossa album, but I was unaware of this Strata-East release and am definitely looking forward to hearing it. Thanks.