Go Ask Alice: That Time When Members of the Wrecking Crew Jammed While Tape Was Rolling

Provocative new/old music from Alice Coltrane, Can, and Pete Jolly

There are days when it seems like the whole world runs on two (OK, sometimes four) measure vamps. They’re everywhere in popular music, a lingua franca that facilitates communication, encourages collective seeking, transcends artificial distinctions of genre. And can, in the wrong hands, become a numbing agent more powerful than novocaine.

The basic recipe: skeletal recurring chord patterns (or a single chord) that gather intensity through repetition. These can inspire just about anything: Simple melodic refrains, throttling feats of instrumental brilliance, polyrhythmic crosstalk, call and response chants.

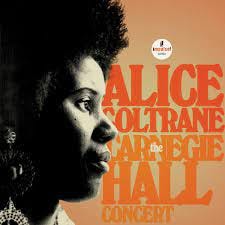

Transforming vamps into music that’s greater than the sum of its structural parts is absolutely an art (see Parliament/Funkadelic, among many others). Yet perhaps because we’re in a moment of Peak Vamp, we don’t always think of this device as having its own aesthetic properties, or even being worthy of attention as a musical device. Until, that is, a previously unreleased document like Alice Coltrane’s The Carnegie Hall Concert turns up, or a similarly entrancing performance by the krautrock band Can in 1973. Or the long-overdue return of one of the more curious moments in the history of ‘70s-era A&M Records, the live-in-the-studio Seasons by Pete Jolly.

Recorded in 1971 shortly after the release of her galvanizing Journey in Satchidananda, the Carnegie Hall performance underscores Alice Coltrane’s profound understanding of the dramatic possibilities of the vamp. It opens with an extended version of the title track from Journey, and for the first two and a half minutes, the focus is on a bass phrase played in powerful unison by Jimmy Garrison and Cecil McBee. This opening suggests a solemn type of internal reflection or meditation, and when Coltrane first strikes the harp strings she magnifies that feeling, with delicate rising-and-falling lines. She’s not exactly soloing in a jazz sense. Rather, she drops planks of carefully voiced chords that brush against the bass ostinato — pulling listeners away from the concerns of the everyday to confront the concerns of the soul.

The vamps on the first two sides of this double LP dwell in that rhapsodic prayer-call space. Side 3, a jaw-droppingly intense version of John Coltrane’s “Africa,” goes elsewhere, possibly startling the Carnegie crowd that was attending a benefit that also featured The Rascals and Laura Nyro. This “Africa” quickly builds into a visceral squall, with Alice, now agitating on piano, coaxing fury from Pharoah Sanders and Archie Shepp. Building from and referencing elements of the vamp and the melody, these two seize Alice Coltrane’s expansive ideas about jazz spirituality and then, with mind-melting brio, take them further. Their often frenetic interplay is one answer to the question “Exactly how far out can a vamp go?”

Can, the German experimental band, used repetitive vamps to different ends – conjuring trance-like inquiries that sometimes unleashed soloistic flourishes, and sometimes just marinated in the shifting currents of groove. We are able to hear Live In Paris 1973 (and earlier titles in an ongoing live-archive series) because a British fan named Andrew Hall snuck a tape recorder into shows; eventually the band invited him to record from a spot in front of the speakers. (Here let’s thank the intrepid Hall and pause ten seconds to marvel at the quaint human level at which the old music business operated.)

Can was curious about texture, and abrasion, and juxtaposition, particularly addressing the ways the electric guitar could coexist with – or slice through – a thick haze of synthesizers. The Paris show catches the band with beloved lead singer Domo Suzuki, who died not long ago. Suzuki’s mystical energy brought the rock-backbeat vamps to a meta level; it hardly mattered whether or not his words tracked as narrative. The journey of track one, “Paris 73 Eins,” lasts thirty six minutes; it’s a diffuse epic. The more manageable “Paris 73 Zwei,” which is set in a Germanic appropriation of the timeless “Who Do You Love?” groove, offers a more discernable example of Can’s vamp exploration.

Alice Coltrane and Can honed their craft in live performance, developing techniques for building, and then sustaining, musical intensity over time. Their art depends on epic expanses; it can’t be condensed into short form.

By contrast, the job of the studio musician is to cut to the chase – to nail the chorus and then, after a verse, nail it again, maybe adding slight inflectional differences. Studio players approach vamps as foundational building blocks – more akin to furniture than pathways to higher realms of expression.

Yet those musicians are terrifyingly good at establishing the contours of a vamp, and then maintaining it at a boil according to the outlines of the written chart. What happens when there is no chart? That’s what Pete Jolly, a jazz keyboardist and fixture of LA studios, asked on Seasons, the Herb Alpert-produced third and final record Jolly made for A&M, a work that’s been sampled by Busta Rhymes and Cypress Hill, among others.

Jolly’s idea was simple: Gather freelance studio ninjas (drummer Paul Humphrey, guitarist John Pisano) and members of the all-ninja Wrecking Crew (bassist Chuck Berghofer, known to all for his immortal solo on the Barney Miller theme song, percussionists Emil Richards and Milt Holland) for a four-hour session with very little material prepared in advance. They did one standard – “Younger Than Springtime” by Rodgers and Hammerstein – and only minimal overdubbing after the fact, including a blaring horn section on one track.

As Jolly explained in the original liner notes, “We literally improvised as we went along – using visual and musical communications between ourselves to let the tunes happen, breathe and expand. It’s as simple as that.”

Simple, sure, but also profound – and an excellent illustration of the sensitivity and deference that’s necessary for creating on the fly, without a script, in the studio. Some melodic ideas seem to erupt out of wandering jams: As the track “Sand Storm” fades in, the crew sounds like it’s drifting, listening for any melodic thread to rise. Pisano drops a simple triplet idea, and immediately the others leap to seize and add to it, creating melody and elaboration in one sweep. Almost all the tunes center on a repeating vamp or phrase, and, crucially, all of them venture, at least glancingly, toward different textures and melodies and settings for short eruptions of beastly improvisation.

Tellingly, everything is short here: These are not heroic climbs up the mountain, they’re momentary accounts of fascinating side trips. Some might be compositionally thin, but like the records by Alice Coltrane and Can, they’re empathetically rich, capturing the abundant, endlessly renewing spirit of interaction exactly as it happened.

Weaving together Alice Coltrane, Can and Pete Jolly - superb writing here.

Great piece. I've been listening to Alice Coltrane and Can this past week; great to see them appear together here and the Pete Jolly material is the icing on the cake!