Feats Not Failing

On the musical values that make Waiting for Columbus an enduring live document

There isn’t much of a conversation around Little Feat anymore. And why is that?

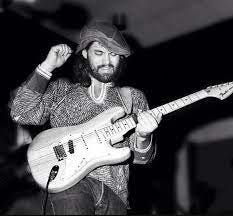

Very few live acts of the ‘70s developed – and sustained – a rhythmic lock like the 6-piece, which despite Southern California roots had more in common with the Meters and other purveyors of Southern Louisiana funk. Even fewer bands had a tw0-guitar front line (Paul Barrere and slide master Lowell George) whose crosstalking ad-libs – crisp electric leads against beseeching blues-slide sustains -- intertwined into a form of whiplashing spontaneous drama.

And even fewer bands have been copied so studiously in the decades since. Early on, Phish copped bits of the Little Feat pocket, then pretty much swallowed it whole; for its Halloween show of 2010, the band re-created the masterful (if not all-the-way live, as discussed below) 1977 Little Feat album Waiting for Columbus in its entirety.

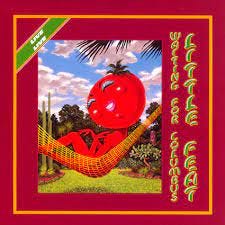

Last Friday Rhino dropped an 8-CD Waiting for Columbus box. It contains a remastered version of the original double LP release, and three full concerts from the summer 1977 tour -- Manchester City Hall, Manchester, England (7/29/77), The Rainbow, London, England (8/2/77) and one of four shows at Lisner Auditorium in Washington D.C. (8/10/77).

Full disclosure: Haven’t heard the whole thing! That’s partly because it’s been too interesting to listen “across” the various shows, comparing different versions of Feat staples like “Willin’” and “Fat Man In the Bathtub” in A vs. B vs. C fashion. This encourages paying attention to slight changes -- in tempo, feel, attitude. It ports you into the nightly work of music-making.

Musicians talk about how non-musical factors can affect the spirit of a performance, and how challenging it can be to reverse onstage sloppiness or any random unwelcome mojo that might be hanging around in a room. (Example: The diffuse, echoey sound of the hall in Manchester.) The job is to transcend those factors – itself a tall order even before considering whatever internal drama might be surrounding the people involved. At that time, George, the group’s principal songwriter, was disengaging; he died xx years later. Band members and others who were in position to know say the Little Feat interpersonal dynamic was toxic on that tour. There were physical altercations. Disagreements over the direction of the group. Abuse of all the favorite road-warrior substances.

Years later, in an interview with journalist Bud Scoppa, Barrere described the band at that time as “without focus or direction, no real managerial control over the business aspect, and because our personal habits were so askew, clear thinking was not a part of the ball game.”

Here’s the thing though: That dissonance doesn’t seem to affect what happens on stage. When they walked out to perform, the members of Little Feat were evidently able to set aside animosity long enough to cooperate on the care and cultivation of the groove. Within seconds of beginning a tune like “Oh Atlanta,” the six agreed on not just the pulse but the grease level within it, the balance of the instruments and the organic, agreeably unkempt blend of the vocal harmonies. Sometimes the sauce is full strength right away – see the swaggering Manchester “Oh Atlanta” – and sometimes it has to bubble for awhile before it becomes potent (which is the case with the D.C. show, which begins with a tighter approach to the Bo Diddley beat that loosens up over time).

Listening in this comparative way, the first thing that comes across is discipline: These musicians were accomplished jammers, skilled in the development of rousing extended solos. Yet they rarely let the solos wander on at length. The focus is always on the song. There isn’t an 8-minute Lowell George epic showstopper here, and that’s great: We hear him framing the verses with weepy, gracefully poignant guitar leads that last maybe four measures. And are perfectly thrilling that way. They leave you waiting for the next one.

That’s a lost art right there, and it provides one answer to the question of Little Feat’s absence from the larger conversation about music-making: We’re not really into discipline these days. We want the fireworks, all the time. The expanded Waiting for Columbus draws a clear distinction between the Little Feat approach and that of the open-roads-forever jam bands who borrowed from the band’s templates. Here are a few other performance aspects that have nearly vanished from the conversation but are inescapable in the work of Little Feat at the time of Waiting for Columbus:

*It’s possible to feel these players listening to each other. They’re not merely executing parts; they’re engaged in the more cosmic task of cultivating an overall feeling – and are not afraid to make adjustments as needed.

*The musicians recognize the value of a common open space, the musical equivalent of a town square. Nobody overplays inside this space. There’s no clutter. The players share a reverence for melody, and also for the conversational volleys that happen between the melody lines. Those lines become magical because they blossom Grateful Dead-style, as the result of communal endeavor.

*Tempo matters. There’s some variation from night to night, but most of the tunes that were regularly in Little Feat’s setlist exist within a fairly narrow range. It’s cool hearing the way small elements, like the age-old rhythm guitar chank-a-chank, shift slightly to help the time cohere. Everybody in Little Feat played time.

*Inside the patterns used by criminally underrated drummer Richard Hayward are echoes of the entire history of backbeat music. Rum boogie brushing against jump-jive against second-line parade stomps against blues shuffles against JBs-style funk, all of it churned into a form of persuasion aimed at the hips first, the feet second.

*Lowell George didn’t need to do any of what Discogs delicately calls “refurbishments” to the live recordings. He did them, and the initial release of Waiting for Columbus is frequently cited among the best live albums of all time, so….the tweaks win and George is a genius. Until, that is, you hear his vocals on the other nights. Sure, they’re rougher. But they reveal him in a great light: He's fully immersed and communicating on a blood-and-guts level that underscores – and then travels far beyond – the words. Same goes for his guitar improvisations: He’s totally apt and mercilessly evocative in the moment. No second chances are needed.

*And as great as the Tower of Power horns are, they don’t add a ton to Waiting For Columbus. The best cameo performance here comes from former Rolling Stones guitarist Mick Taylor on “A Apolitical Blues.”

*The songs were made for live. George wrote tunes that sounded like they were erupted spontaneously during the last set of a sweaty club gig – “Willin,’” “Oh Atlanta,” and others. The band also knew how to massage and rework the songs of others into bracingly unique experiences: Any of the versions of Allen Toussaint’s “On Your Way Down” included here could be regarded as the definitive interpretation.

Yes, we have a digital suggestion box. Share your overlooked/underloved records at: echolocatormusic@gmail.com.