Let’s start with something real.

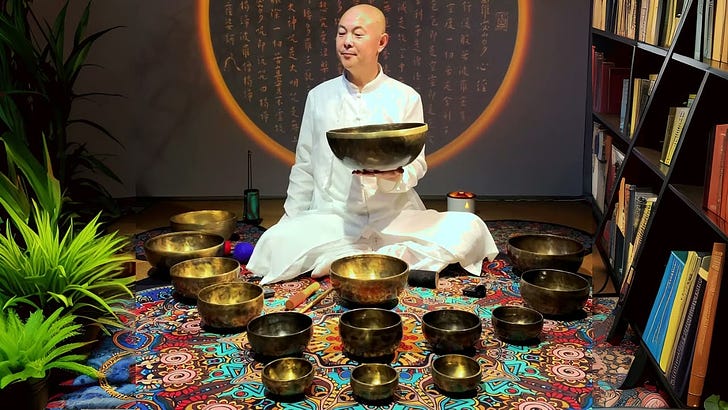

Suspending cynicism for just a moment, we see a man sitting crosslegged, surrounded by metal bowls. He’s striking them with mallets in, to borrow the argot, a mindful way. The idea is to get the bowls vibrating at particular frequencies that encourage calmness, or accompany meditation. Does it work? There are studies available, including several on National Institutes of Health sites, but really it’s possible to tell if it works for you just by listening for a minute or two. The bowls don’t “speak” to everyone in the same way.

Whether they “work” or not, our senses tell us the bowls and the sounds are genuine. Made by a human in real time.

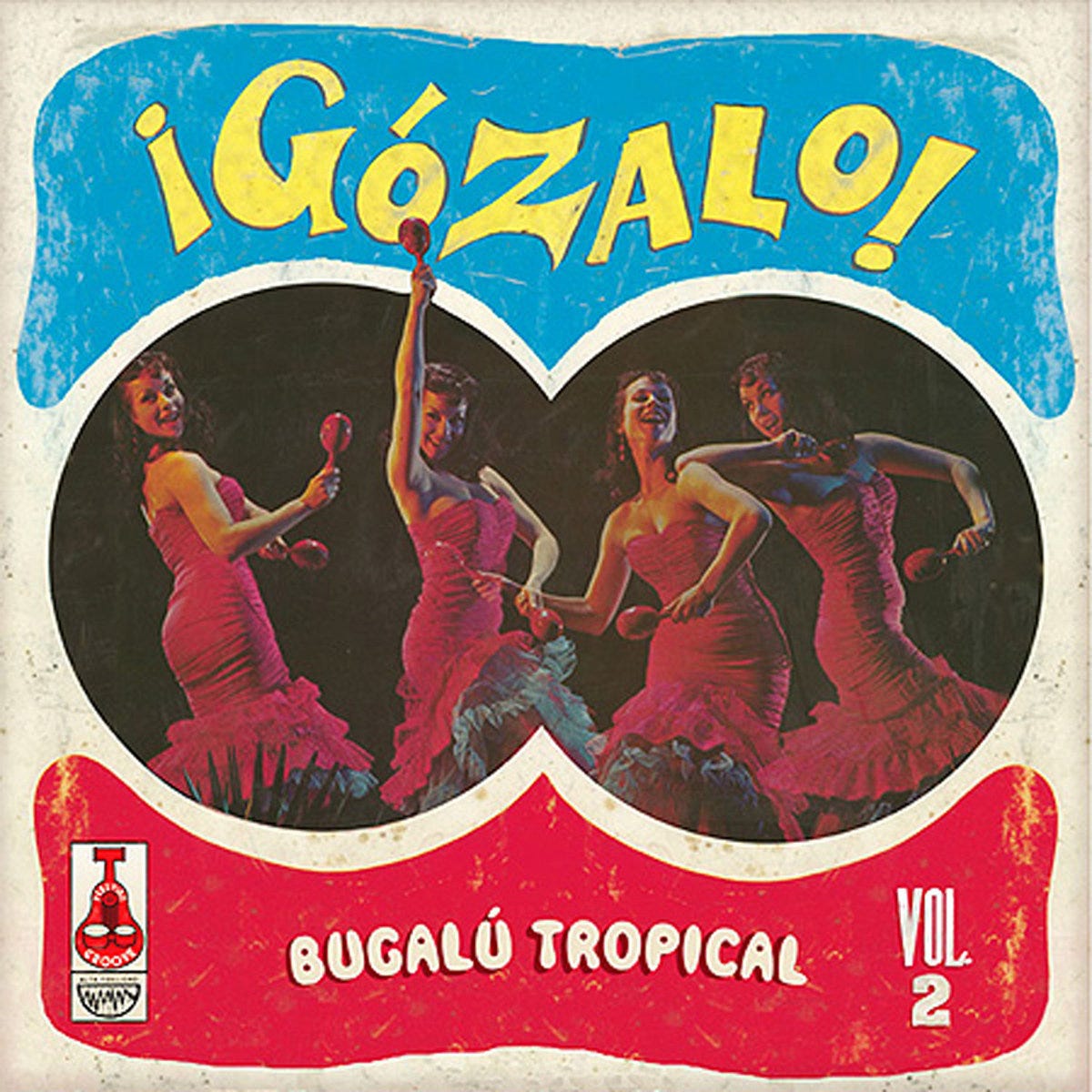

What about this?

Looks generic. Possibly grey market. Possibly another of the rapidly proliferating AI-derived fakes — a Various Artists compilation from a long ago that never existed, except in the bowels of some server farm.

Turns out this is a record filled with actual relics unearthed by Spanish reissue label Vampisoul. It’s the second volume surveying Afro-Cuban music that erupted in Peru in the 1960s and ‘70s, much of it documented by Manuel Antonio Guerrero on his MAG label, which I’ve written about before. The group on the track below, recorded in 1968, is a label creation: None of Los Guantanameros hailed from the Caribbean, and none of the musicians, which apparently included guitarist Rafael Rios from another label band Los Guajiros, were credited on the initial release. It was just a session, on a day in the studio — with the details that are obsessed over by collectors lost to the winds of time.

The music sounds genuine enough — nice guitar work! — and has that wonderful lo-fi patina associated with analog studios in the dusty old days when they rolled joints on mixing consoles. So: Yes real, but lacking documentation.

What about this?

Why, it’s the long-lost second album from the Shu Brothers! Those intrepid crate-diggers from Temple of the Acid Fist finally snagged it — along with the group’s long lost 1967 debut Journey From the East, which, according to the notes, was banned by the Chinese Communist Party for “for being too funky.”

This one is easy to spot: The artist credit on YouTube includes the parenthetical “(Fictional AI Band).”

I’m not going to dwell on the musical attributes (though a tip of the chapeau goes to ChatGPT for the period-accurate snare sound on the drum machine). I’m also not going to itemize the (several) hours I spent listening to the label’s offerings — do you see the lengths we go here at Echo Locator to bring you these fascinating curios?

I will, however, pass along a response posted by Temple of the Acid Fist in the comments, endeavoring to explain the process: “Vague instruction will still create a generic song, but very specific instructions can create specific sounds, keys, rhythms, instrument references, vocals, styles, melodies, lyrics, etc. At risk of giving myself too much credit, the AI does generate the music. My role is to write the specific prompts and lyrics; the more involved and specific, the more exact the song. The less specific, the more random the outcome. They [the AI bots] don't usually recognize artist names, so I've found myself doing a lot of research on the individual components of various sub genres to build or mix a particular style.”

Elsewhere in the vast Temple of the Acid Fist archives are AI bands exploring “Turkish Psychedelic folk-rock” and “Thai Rock of the ‘60s and ‘70s.” Another gaslighting label, Zaruret Records, offers a detailed history of the fake 1960 debut of The Vermeers (!), explaining that the music “delves into the British Folk Rock Blues genre.” Oh the earnestness of the cover image….

Takeaway: This is endless. Destabilizing to an already swamped ecosystem. And destined to further erode (or, taking the opposite view, expand) commonly shared definitions of art.

Isn’t it ironic? At a moment when streaming services are doing very little to address (or even identify) content generated wholly or in part by AI, they’re working overtime to limit the pool of human artists eligible for compensation. In the torrent of endless content options, the AI wins on novelty value alone; already a slice of the audience is in the thrall of machines making human-ish sounds, writing human-ish songs. Not questioning their enduring resonance or artistic contribution.

Eventually, though, the “Is this real?” game grows tiresome, and we’re forced to ask “Where are our priorities?” Here in the Wild West prehistory of AI Art, music listeners shouldn’t have to wonder about the creative provenance of every track, or the (already muddy) issues of copyright surrounding these replicas of existing works. The technology moves rapidly; even the most astute futurist thinkers can’t grok, with certainty, what the collateral damage to capital-A art might be.

We come to music for many things — to be healed, to be physically swept into a kinetic rhythm, to be jolted out of the mundane, to witness a painstaking excavation of truths and lies. These expressions begin within creators as stirrings or emotions; they come from a soul place, not a 3D printer. A machine can capture the outlines. But only the outlines.

**

Confession: I am more dispirited than I was before I entered the Temple of the Acid Fist. For a while this past week I wrestled with posting this, with shining any light on these “projects.” Because they seem like idle curiosities — distractions, really — at a time when the majority of living breathing musicians are struggling to survive, and face steep daily challenges trying to captivate anyone in our attention-diminished culture. Music takes time to savor; people no longer accord it the time, or the respect. They’d rather cue up “Hotel California” for the millionth time. Or giggle at what the AI did to Kung Fu soundtracks.

While working on this, I spent time with an unusual “repurposing” project that comes out this week: Sean Ono Lennon’s spectral “Meditation Mixes” of John Lennon’s single “Mind Games.”

That’s right, starting Friday it’s possible to purchase a 3-LP set (!) of 9 distinct audio environments drawn from the tracks of the original. The one above, “Yes,” is the busiest of them, using more of the source material than the others. Four of the tracks are presented as “Binaural” — in which different frequencies are sent to left and right channels and combine to produce a new frequency. As the Lennon website says, these focus on four types of brain waves (Beta, Delta, Gamma, Theta) and “can activate different brain patterns for scientifically proven therapeutic effects.”

Science aside, these are engrossing as music or meditation backdrop. They contain echoes of Lennon’s indelible vocal set into enveloping oceanic tides of drones and carefully massaged noise. They offer a promise of slowness, substituting a steadying and serene vastness for the hard and fast “text” of the lyrics.

It’s another thing to be cynical about — “Mind Games” recontextualized as a corrective to the jittery monkey mind Lennon so elegantly described in the song. But at the very least, when you hear a distant trace of Lennon singing through the ether, one thing is abundantly and instantly true: That voice is real.

I’m disappointed (not surprised in the least) that the streaming platforms are making no effort to identify AI-generated content. I would definitely like to know the source of the music I’m listening to. Better yet, I’d like to opt out of all AI-generated content. Wishful thinking I’m sure.