Do-Over!

Entering the echo chamber of reverential re-creation with Cunningham Bird and Startling Music

Way back in October, I held my tongue when Madison Cunningham and Andrew Bird released Cunningham Bird, a song-by-song re-imagining of the 1973 Buckingham Nicks album. The original is a rich, if imperfect, snapshot of soft-rock during one of its peaks; its best moments channel the earnestness of the time into melodies of disarming resonance and depth. Though it wasn’t a hit, its ideas became foundational to the hitmaking run of Fleetwood Mac.

[Want to hear precisely how foundational? During brief tours before Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks joined Fleetwood Mac, the duo performed songs it workshopped after the release of Buckingham Nicks. One of them, our old friend “Rhiannon,” was captured by fans on three occasions. The below video, which includes all three, shows Nicks’ rapid growth as a songwriter as well as the duo’s shared instinct for apt, nothing-fancy orchestration and vocal harmony. No exhaustive comparison with the Fleetwood Mac version is necessary: The bones of the subsequent megahit are in place.]

I planned to cover the Cunningham Bird update because the songs are smart (some are still underloved), and because these are two prolific artists who are not afraid of the hard left turn into uncharted waters. On a technical level, the re-do didn’t disappoint. The duo stretches some of the melodies into moments of unexpected tension, alternating between simple close harmonies and wider, keening, less conventional intervals. The tone varies from verse to verse, as Cunningham and Bird conjure folk placidity one minute and modern alt-pop the next. Each shift is gently underscored by Bird’s plaintive violin and other unfailingly graceful instrumental touches.

For all the craft, the songs don’t exactly bloom the way they do on the original. The remakes somehow diminish the material, narrow the perspective of the narratives, and make the initial inspirations seem slightly like repertory etudes to be modeled. Maybe it’s that the vocals are too pristine – the songs want some of the raw, shouting intensity that the young Nicks committed to tape.

I shelved what I wrote in October. Didn’t want to put anyone off of either the original or the tribute; both remain worth hearing. But I couldn’t shake the questions surrounding the very act of revisiting a known work: Beyond throwing some light on the initial album, what’s the point? Is it simply an act of reverential re-creation, to be marveled at? If so, does it bring listeners closer to the genius of the original? Does it provide some hindsight context on the (dizzying) moment when the work was created? (On this last point, I’d argue Cunningham Bird does not….).

I began looking around the nooks and crannies of recorded music for other instances of artists diving fully into a known album. Wes Montgomery’s chart-topping A Day In the Life doesn’t qualify, even though in addition to the title track, it has a crafty cover of another Beatles’ classic, “Eleanor Rigby.” In the early ‘70s there were many albums of synthesizer recreations of works from pop and classical music – see Wendy Carlos’ landmark Switched On Bach and pianist Dick Hyman’s 1969 covers experiment, The Age of Electronicus, discussed a few years back in this space.

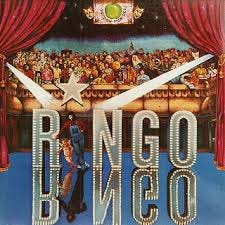

The synthesizer was a logical lane for this inquiry; it was a novelty, regarded with gee-whiz fascination in the early ‘70s. Eventually, the gods of obscurity smiled and I stumbled onto a supremely kooky yet still somewhat musically credible do-over: David Hentschel’s Startling Music, a 1975 release on Ring O’Records, in which the esteemed synthesist and producer (Genesis, many others) re-interprets the songs on label honcho Ringo Starr’s 1973 Ringo. That’s the Starr record with “Photograph” (the hit co-written by Starr and George Harrison), that features contributions from the other Beatles, Levon Helm and others from the Band, Marc Bolan, Harry Nilsson, Jim Keltner and James Booker. (In a real sense, Starr’s long-running All-Starr Band has its origins here.)

For obvious reasons, Hentschel – who owns some rock immortality for creating the lavish and expressive ARP 2600 synth fantasia that opens Elton John’s “Funeral for a Friend/Love Lies Bleeding” – had to be somewhat faithful to the Ringo songs. He offers two takes on “You’re Sixteen;” one’s set to an agreeable erstatz reggae rhythm, the other is a brief calliope-and-brass concoction that feels like it wandered out of an 1890s medicine show. And as on “Funeral for a Friend,” Hentschel develops a blustery yet sonically lush prelude to usher in “Photograph.” Sadly, after that invention, he pretty much just plays the song straight; it loses steam fast. On rock-leaning pieces like “I’m the Greatest,” the grooves evolve into deeper and more entrancing patterns – thanks to the presence of the ripping good Phil Collins, who handles drum duties throughout. Below, an unauthorized YouTube version of the album, which has not yet seen a digital-era reissue.

Startling Music is not a lost classic. It’s more like a lost curio, from a moment in time when K-Tel was extending the shelf-life of hit singles and a figure like Starr could commission a vanity recasting of his hit album, just for kicks. But it involves some genuine creativity, showing how a musician like Hentschel, who understands the coloristic potential and expressive power of synthesizers, can extend and re-imagine even the simplest pop ditty as something slightly (at least) strange.

So, maybe not high art. But it makes me smile all the same. Maybe that’s because these last two weeks have been short on any kind of levity – in addition to all the direness of American politics, my feed has been filled with dismayingly spot-on essays about art-making and the mostly vanished practice of arts criticism. This one, How Art Lost Its Way by the critic William Deresiewicz, laments in satisfyingly blunt language that the most salient feature of many forms of American art since 1990 has been stagnation. “Since then, and especially over the last 20 years, it feels like we’ve been trudging in a circle.”

Where’s that Ouch of Truth emoji?

The do-over impulse can be read as one symptom, among many, of this stagnation. Naturally there’s more of it on the horizon: Recently Blue Note Records announced that for his label debut, saxophonist Branford Marsalis is bringing out a song-by-song homage to Keith Jarrett’s 1974 masterwork with his European quartet, Belonging, Releases March 28.

Ha! Good one! Long ago I relegated all Tusk-related memories to a little-used cobwebbed corner of my brain.

I am surprised you didn’t discuss camper van Beethoven’s cover album of tusk?