As a child of analog, I think constantly (and write at probably too much length here) about the aesthetic ideas and performance approaches of earlier eras that are in danger of extinction in the digital age. There’s much to lament – like even something small like the ensemble execution of a grand rallantando, or a precise swell in volume. Those often-tiny aspects that bring dimensional richness to sound.

Here’s an idea that’s not vanishing, but returning in a promising way: Artists taking grand swings at genres of music that are far from their home turf. In ways both similar and distinct from an antecedent like Ry Cooder, Jonny Greenwood of Radiohead has developed a series of memorably tense, carefully arranged film scores including The Power of the Dog; his solo projects include a thrilling collaboration with Indian musicians (Junun, check it out!) and forays into contemporary classical music.

There’s a long list of talents who are known in one realm while making determined, erudite forays into others. Jazz musicians have of course been doing this for a while – Anthony Braxton is one towering example, inspiring younger artists like pianist Brad Mehldau and guitarist Mary Halvorson to create scores and settings that utilize improvisation as one tactic among many. In between contributions to the 8th and 9th Taylor Swift records, multi-instrumentalist Bryce Dessner of the National has been commissioned by the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Kronos Quartet and others; he’s written ballets, film scores and music for a visionary classification-defying group called Dream House Quartet built around pianists Katia and Marielle Làbeque. This group is about to make its US debut at Town Hall and will release an EP, its first recording, later this spring.

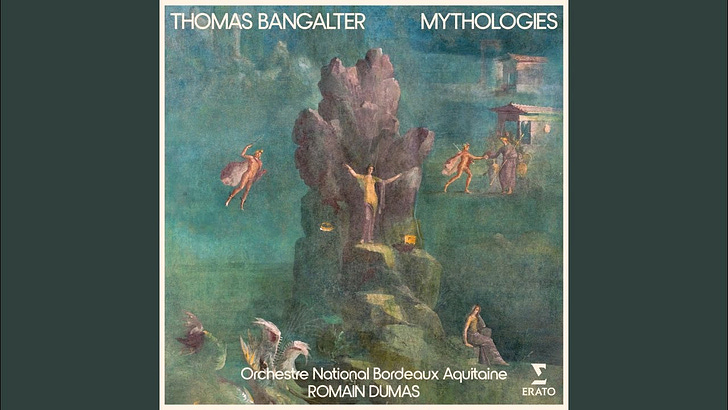

Last week brought another big-name large-budget work that’ll inevitably get tagged as “crossover”: Mythologies, a 23-movement ballet created by Thomas Bangalter – who for a long time was better known for the crisp electronic textures of Daft Punk. Mythologies was conceived by the choreographer Angelin Preljocaj and recorded by the 50-piece Orchestre National Bordeaux Aquitaine under the leadership of conductor Romain Dumas for the French Erato label. In a recent New York Times piece about the work, Dumas described it this way: “It’s a break of medium, but he (Bangalter) is the same person.”

That means that though the 90-minute work is entirely analog, it shares the sense of animation and intricate rhythmic architecture that set Daft Punk apart from many acts associated with electronic dance music. The group, which issued its debut Homework in 1997 and announced its demise in 2021 almost a decade after its last album Random Access Memories, blended modern and vintage dance styles (house crossed with disco, etc.) with airborne, almost wonderously graceful pop melodies. This blend was crucial to the evolution of EDM – Daft Punk was among a small group of catalysts bringing slippery shape-shifting textures and jittery arpeggiating synthesizers into the pop mainstream.

And Bangalter and longtime partner Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo worked the image game brilliantly. In every story about the new Mythologies, there’s at least one prominent mention of Daft Punk’s stage getups – gleaming stage platforms like spaceships featuring the two in robot-style headgear and high-tech suits, with their faces entirely obscured. The Times story features photos of Bangalter in his Paris home, looking like a well-adjusted 48-year-old artist.

The path Bangalter took to Mythologies was not exactly Drop-The-Bass direct: He read books on classical composition and orchestration (including one by Hector Berlioz), and worked to learn the nuances of writing for groups of stringed instruments. He applied these techniques the way a clever student would, and didn’t worry endlessly about every note being original: The ruminative “L’Accouchement” dwells in a somber, thick mood that recalls Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings, while other segments have the thrumming tympani-punctuated intensity of Beethoven’s symphonic works, or dramatic pitch-bends in the lower strings that mimic the sudden swerves of glitchcore. Still others build tension with repetitive rhythmic devices, or cells, that recall those used by Steve Reich and others associated with minimalism.

Beyond the distinct elements there’s this: Just about every one of these 23 sections celebrates motion. Bangalter is writing for dancers on a stage – not rave denizens whose hips have been unlocked by some exotically wicked drum programming. Still, the energy of the act of dance is inescapable: At times it seems as though he’s having an internal dialog about what might be universal about dance, what elements are vital to its transformations of simple gestures into art. Coming from a style that’s centered around rhythm, he understands groove hypnosis; there are times when his writing nudges the orchestra in the direction of a similar effect. But because it’s an orchestra, the impact is different, as he told the New York Times: “To write a chord or a melody and have the performers — human beings — play it and have this instant emotional quality to it, is really quite exhilarating. It’s not the fight you have against machines.”

That’s a reason to pay attention to Mythologies, and whatever Bangalter does from here: He’s connecting ideas between disparate approaches and genres, seeking ways to broaden the entrenched thinking of one sector by ever-so-slightly introducing techniques from other realms. Whether or not this piece is regarded as “successful” – and some early reviewers have harped on Bangalter’s debts to late 19th century masters – its variety and sprawling ambition is an encouraging sign of health. It aligns with not just recent compositions from Greenwood and Dessner but also works by David Amram and Frank Zappa – artists who started in one place and went elsewhere, and left the entire terrain forever changed.