Patsy Cline: Imagine That: The Lost Recordings (1954-1963)

When critics and historians talk about Patsy Cline, there’s usually a parallel sidebar discussion about the influence of her producer Owen Bradley. It goes something like this: Did the legendary producer push too far into easy listening with the “countrypolitan” sound he pioneered on her studio recordings? Did he, over time, limit Cline’s creativity by pinning her down in a plush, gorgeously appointed pop-singer corner?

The Cline legend is long. But her discography is short – just 24 singles and three studio albums, a small enough sample size to render any decades-later armchair conjecture about woulda and coulda a bit of a hollow exercise.

Now entering this chat is Imagine That: The Lost Recordings (1954-1963), a sonically stunning 2-disc anthology that is easily the most historically consequential release of Friday’s Record Store Day.

Spanning nearly the entire length of Cline’s career, it presents her in less starchy surroundings: There are demos of songs that later became hits; these sometimes involve just a few musicians, and the unobtrusive accompaniment magnifies the sun-like radiance of her voice. There are performances from radio and television that show what a sensitive singer Cline was – among them a serene, wonderfully patient rendition of “Just a Closer Walk With Thee” that catches Cline shifting between lead and harmony roles. There are dazzling pieces like “Got a Lot of Rhythm in My Soul” that glide along on pure exuberance, making the argument that while Cline’s reputation was built on the dejected, open-hearted ache of her torch songs, she was also capable of sending wild sparks through uptempo rock-influenced rhythms.

And can we talk for a minute about phrasing, Cline’s instinctive ability to shape just a few words or notes into a lasting, luminous, perfect creation? These intimate, less-choreographed tracks show that Cline understood not only exactly where to place her emphasis for maximum impact, but also precisely how much to bend a note (and for how long) to convey emotional worlds beyond the words. Cline wasn’t a blues singer by trade, but her two performances of “Lovesick Blues” illustrate her almost superhuman control of swoops and yodels and flatted-third blue moans. Incredible.

Zev Feldman, the reissue detective who helmed this project, included some interesting spoken audio as well – song introductions and thank yous, and a short Cline monologue from a concert in Atlanta, during which she thanks fans for their support after her car accident. “The greatest gift you folks could have given me was the encouragement you gave me right at the time when I needed it the most.”

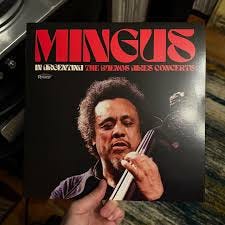

Charles Mingus: In Argentina: The Buenos Aires Concerts

Not quite two minutes into “Three or Four Shades of Blues” from this live document, the tempo falls away. Out of the unexpected silence pianist Robert Neloms begins earnestly playing what could be an English folk song. It’s an odd choice, and Neloms makes sure listeners sense this by stating the melody plainly, and then stating it again. Charles Mingus enters with an echo of the second theme statement, and then, after a brief moment of near-stillness, the bassist barrels into a walking blues at a slightly different pulse. Pretty soon Neloms is quoting “It Might As Well Be Spring” and the groove is trending high and the mood is again all spangly and bright.

It’s one of several programmatic interludes on The Buenos Aires Concerts, which happened over two nights in 1977 and capture Mingus’ late quintet at an interesting moment. First because drummer Dannie Richmond had returned to the group, bringing with him the elemental, streamlined rhythm that was integral to Mingus’ concept. And then because the band — which included the frontline of spitfire trumpeter Jack Walrath and saxophonist Ricky Ford — was touring to support Mingus’ elaborate large ensemble LP Three of Four Shades of Blues, and having to adapt some of the written material for the smaller group.

The solos are reliably blazing, but it’s the gear-shifts — extraordinarily unified swerves in and out of interludes and tempos — that make In Argentina essential for study in jazz school (!) and elsewhere. On many new releases of contemporary jazz, it’s painfully common to hear the whole band playing at peak intensity from start to finish, with soloists dispensing all the right notes in increasingly complex clusters. The result is something undifferentiated — music that’s topheavy with informational virtuosity yet empty where what Max Roach called the “story” should be.

These Mingus performances are the reverse — they've got dramatic climbs and sudden moments when one instrument is lonesome and alone, playing at a whisper. And everything in between. Each contrast, every surging eruption, adds something to the unfolding narrative, sparking a bit of suspense or bafflement or fury on the bandstand. Throughout, there’s a sense that the players are listening, in that full-aborption way, to hear what next dimension they might discover. And we’re there, discovering it with them.

Bobby Charles: The Bearsville Studio Sessions (Rhino)

Bobby Charles Guidry, plainspoken oracle from the small creole town of Abbeville, Louisiana, was not exactly well known during his lifetime. But he turns up in interesting places in the rock and roll footnotes: As the composer of “See You Later, Alligator,” a huge hit for Bill Haley and the Comets in 1955, and of “The Jealous Kind,” which was first recorded by Clarence “Frogman” Henry and later Joe Cocker and Ray Charles. His first solo album, Bobby Charles (1972), was recorded at Bearsville Studios near Woodstock and co-produced by Rick Danko of the Band – it’s sometimes referred to as the “lost Band album” because it features just about every Band member. (Other key contributors include Dr. John, Amos Garrett, Ben Keith, Bobby Neuwirth, David Sanborn and Geoff Muldaur.)

Despite the participation of those boldface names, there’s no grandstanding anywhere on Charles’ sly and low-key album. Its ambling, rustic aura sometimes masks Charles’ observations and commentary. Its lyrics address the big questions, like the pettiness of people in small towns or the proper ratio of work to play: On the Mark Twain-ish “Street People,” Charles wonders “Who’s gonna work and make the economy grow if we all hang out in the street?” His answer: “Well I don’t know and I don’t care, just as long as it ain’t me.” Truly, an oracle for our moment.

Here’s his transcendent “Down South in New Orleans” from The Last Waltz.

There have been several reissues of this album over the years; in 2013, Rhino Handmade offered a limited edition CD-only boxed set containing the official album and an entire disc of rarities. For this year’s RSD, Rhino has cleaned up and remastered 12 of those rarities for the single LP Bearsville Studio Sessions. This opens with a piano and voice demo of “New Mexico,” then features simple, pastoral, very Big Pink captures of Charles’ songs – among them his unofficial “mission statement” “Homemade Songs,” a plaintive version of “The Jealous Kind” and “Nickels Dimes Dollars.” While not as “essential” as the album itself, these are worth hearing, just to enjoy more of Charles’ easygoing, bliss-seeking songs, and bask in the tender collaborative spirit of the sessions.

Huh? None of the musicians I write about were or are "clients"! and I mention Bob in the piece! yow!

The Mingus is a great set - thoroughly enjoyed previewing it over the past few weeks.