Another idea worth saving from music culture of the 1960s: Collectives designed to support and inspire creative endeavor.

As in: Groups of musicians getting together to explore original music and then bring those creations to the public. The history of jazz was molded by individual trailblazers (happy birthday, Thelonious Monk!) and the efforts of groups – from the big bands to organizations like the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), which was formed in Chicago in 1965, and inspired countless similar regional outfits united by the desire to create opportunities for improvising artists.

[Then came the grants to provide institutional support for these collectives, and……that’s a rabbit hole we’ll tactfully save for another day.]

The impetus for the jazz collectives of the 1960s was both practical and aesthetic, as Reppard Stone, a retired professor of Jazz Studies at Howard University in Washington, D.C., told Jazz Times in 2019. “Musicians weren’t working and because they weren’t working, they were not communicating with others, and being unemployed for a while, one would want to talk about his craft and seek other musicians to communicate with. This is why you see these collectives forming.”

The collective served as a kind of pre-digital “network” connecting musicians with each other and audiences. These took on different structural forms. The AACM’s stated mission is to welcome all genres and styles of music; in addition to organizing live performances and providing artists support around gigs, it operates a school that teaches music fundamentals. Other groups, like the Asian-American collective Asian Improv or the Jazz Composers Collective, are concerned with the needs of specific constituencies.

The business models reflect a range of strategies for funding and promotion, but the motivation today is the same as it was when the collectives first formed in the 1960s: To generate art and employment. And, crucially, lamentably, all these decades later, the groups are still involved in countering the institutional racism of the arts-presenting world. Douglas Ewart, a founding member of the AACM, recalled in an interview that “The segregation in the city (Chicago) made it imperative for finding commonality in musical direction and self-determination.”

These collectives are experiments in team-building – but not of the sort championed by those buzzword-slinging corporate consultants hired to create “positive work environments.” They involve the musician/stakeholders in the (often lonely) task of advocating for art, and the even-trickier work of developing new sounds and approaches.

In the collective dynamic, there are expectations for participants. Members of a collective usually have some working understanding of history (it’s difficult to explore new waters if you don’t know a little about where the ship has been) and also a sense of shared aesthetic. Players show up for each other, and hold each other accountable to the overarching ideal, sonic identity and aesthetic of the group. The approach, very much part of the ethos of the 1960s, contrasts sharply with the bellicose individualism of our current moment; one wonders if the experience of cooperating in small groups, even ones dedicated to “outsider” music, fostered a tolerance and respect for otherness that could prove useful to our contentious modern tinderbox.

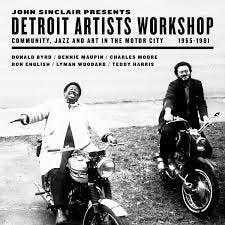

This week, a window opens onto a collective that is well known amongst musicians but hasn’t been thoroughly documented: The Detroit Artists Workshop, which was started in the mid ‘60s by the poet, musician, activist and artist manager John Sinclair, who as a manager took the proto-punk band MC5 from Detroit’s Grande Ballroom to worldwide acclaim.

Sinclair sensed there was a vacuum in the cultural life of his city. “In the mid-‘60s, Detroit was nowhere,” explains Sinclair in the notes. “A decaying jazz scene, no community of poets, painters or writers.” A student at Wayne State University at the time, Sinclair teamed up with trumpeter Charles Moore to unite musicians with the goal of providing rehearsal space and live performance opportunities in the city. The Workshop, which was active until the early ‘80s, presented marquee touring artists (Donald Byrd, Herbie Hancock, Sun Ra Arkestra) as well as many of the city’s rising progressive improvisors – including guitarist Ron English and organist Lyman Woodard.

Those performances were frequently recorded, and some fiery ones appear on the new John Sinclair Presents Detroit Artists Workshop: Community, Jazz and Art in the Motor City 1965-1981 (Strut Records, UK). There’s a spirited quartet version of “Water Torture” by gifted Detroit multi-instrumentalist Bennie Maupin, who was later part of Hancock’s Mwandishi band and appears on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew and Jack Johnson. There are several interesting Donald Byrd tracks and three extended glimpses of a group called Detroit Contemporary 4 featuring English and pianist Stanley Cowell. The album closes with blistering early Latin-jazz fusion from the Lyman Woodward Organization.

Though the sonics are not always pristine, what comes across throughout is pure questing spirit. It’s clear these artists are playing for their peers and like-minded listeners – there’s a sense that this isn’t another commercial gig, but rather a chance to explore at considerable length and depth, in a collective dynamic where sympathetic listening is as important as the notes.

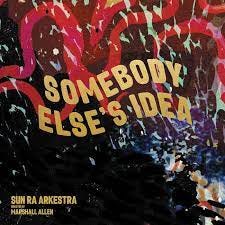

There’s no better enduring example of collective musical endeavor on Planet Earth than the Sun Ra Arkestra, and this week brings more proof, in the form of the new Living Sky (Omni Sound). The group, centered around 98-year-old alto saxophonist Marshall Allen since Sun Ra’s death in 1993, has toured steadily for years without new albums to promote. The 2020 Swirling was the group’s first new studio record in two decades, though the torrent of rare and archival releases has continued at an impressive rate. (The Wikipedia entry describes Sun Ra’s catalog as “one of the largest in music history.”).

Living Sky is a moody, sneaky masterpiece – less boisterous than many earlier LPs but no less intense. In many ways, the downcast vibes make the work riveting, by creating placid contexts for the soloists to disrupt. The opening “Chopin,” a reimagining of Fredrick Chopin’s “Prelude In A Major” first recorded by the Arkestra in 1990, dwells in a settled, easygoing Afro-Cuban groove that suggests a meditative state. Allen blows through that with gleeful abandon, spraying impulsive knots of saxophone fury across the otherwise settled proceeding.

A lumbering, almost mournful track with the delightful title “Someone Else’s Idea” spotlights another aspect of the remarkable continuity of the Arkestra: It’s built around a recurring chordal pad, and as they play it, the horns vibrate as one body. They phrase together with the easygoing precision of Sun Ra’s groups of the 1960s, carrying echoes of the old big bands (especially Fletcher Henderson) into the digital age. But theirs is not kitschy nostalgia. It’s a harmonic- convergence healing agent, the timeless sound of a bunch of musicians breathing together to change the energy in a room (or the planet). That act – the working together to create audio provocation one minute and audio salve the next – that right there illustrates the enduring power of the collective.

Yes, we have a digital suggestion box. Please share your favorite overlooked/underloved records at: echolocatormusic@gmail.com.

Thank you as always!!!!!