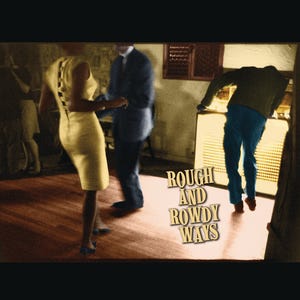

BOB DYLAN

Rough and Rowdy Ways

Columbia (released 6.19.20)

Wrap this in a mask and put it in your Covid time capsule.

Set it down next to that pristine vinyl copy of Highway 61 Revisited and see what they have to say to each other. The flickering awakening of an optimistic generation slammed into the narrow-eyed cooped-up conspiracy theories of the differently doomed.

Take these bedraggled new Bob Dylan songs apart, line by funereal line. Make a list of every public figure and every thing mentioned. Presidents and bluesmen, Anne Frank and Edgar Allen Poe, Leon Russell and Art Pepper, thrown together helter-skelter — or, maybe, on purpose, in careful juxtaposition. A mosaic of innocence and inspiration, held up for your delectation by the crank talking Judgment Day at the Black Horse Tavern on Armageddon Street. Whose stated mission is to “bring someone to life, balance the scales.” Take what he says on faith and don’t bother asking questions, because he’s “not gonna get involved in any insignificant details.”

What emerges from those crowded new Dylan lists? What will the takeaways be after the lit-crit types crunch every last kernel of data? The songs and incantations of Rough and Rowdy Ways are not always even songs — they’re more like sudden weather systems that gather up all kinds of cultural dust and debris and swirl them into a nonlinear post-narrative Meaning Storm.

Here — please enjoy a chopped-up version of the received wisdom in your yammering blogs. Here are all the words and boldface names from your gassy self-involved podcasts, rearranged to signify something different. How was your experience? Take our short survey.

In his first new music since 2012’s Tempest (and, for that matter, his 2016 Nobel Prize), Dylan plays updated versions of his familiar roles — thinker, archivist, trickster, historian, hero and villain. Follow him down foreboding streets where “What are you lookin’ at?” is a challenge not a question, and see where he winds up. He’s a proudly unreliable narrator (“I’m nothing like my ghostly appearance would suggest”) who boasts like a boxing promoter and traffics in grim portents while begging for help from the “Mother of muses.”

Like he needs any help. His voice is raw and unslept and betrayed — he sounds anxious and trapped, like locked-down souls feel. The cracks and contours of his vocal instrument convey a story behind whatever the story is. His language is clipped and telegraphic, with no excess; he’s telling epic tales in code.

Connect the dots on your own time. The typical Hollywood story arc is absent or profoundly secondary here. Broadcasting from the thick of the torrent, Dylan spends little time on details, and less time explaining. He elects to just drop names instead. He says there are no metaphors at work here (whatever Bob!) but his trust in the power of a reference is absolute: The latter part of the 17-minute “Murder Most Foul” finds him ordering a smart speaker to cue up Billie Holiday and Kay Kyser and Nat King Cole and the Grateful Dead and Thelonious Monk, among many others.

Each invocation is prescriptive in some way — hear this and you will be enriched — but they’re also little episodes of history, symbolic stories that intersect with the broader movement of the culture in the 1950s and 1960s. When Dylan does linger on a single figure, as on the blistering “Goodbye Jimmy Reed,” he captures not just the totemic outline of the bluesman’s biography, but the infectious spirit of his art: One hardswinging verse observes “I need you like my head needs a noose.” Another echoes a blues trope with the lament “I can’t play the record ’cause my needle got stuck.”

In a recent interview with historian Douglas Brinkley in the New York Times, Dylan says that his new songs were written on instinct, in what he describes as “trance state.”

What flows from that place is a river of ideas — with grim ghost apparitions running alongside almost giddy celebrations of love and lust. Some unfold in the manner of an idle afternoon reverie, one slowly-mulled thought at a time. Some are more impulsive, whispering the news that if apocalypse is coming, by all means dance. The band helps with that: In addition to shepherding Dylan through beautifully placid, almost tempoless atmospheres (“I Contain Multitudes”), they summon a sweaty, salacious, impossible-to-ignore swing for the album’s several higher-zen updates of the blues.

History tells us that every calamity has its own defining shape. With his 39th album, Dylan suggests that the one we’re living though has a distinct tone as well. Populated with towering figures from less-tumultuous times, this haunted and haunting collection functions exactly like a time capsule, celebrating moments from the past as salve and solace. Open at your own risk.