Been thinking about Billy Preston ever since Get Back.

We talk about him as the “glue” on those sessions, as much for the genial vibe he radiates in the room as anything else. He’s smiling, open, calm at the keyboard. He’s been described as a “steadying force” on the Beatles during a turbulent moment, a fact the footage makes clear.

Then you listen to what Preston plays on “Get Back,” and it’s not exactly earthshattering. He’s not stealing any shine from anyone. He’s playing rhythm, providing a little squabbling riff and then participating with the whole band in the chordal syncopation that gives the hook its power. Even his brief, dancing “solos” are oriented entirely around the pulse.

Preston’s intentional approach to the support role offers a deep lesson for those striving to create music that feels good. Because what he was doing in the early ‘70s – with the Beatles and the Rolling Stones (he’s on “Shine a Light” from Exile on Main Street) and Sly Stone as well as on his own records – amounts to an index of devices that are essential to the vital and often overlooked art of stirring the pot. It’s humble work, background work, this groovetending. It involves restraint, and minute-by-minute editing. It thrives on repetition. It prizes steadiness over grandstanding. It is deliberate, and deliberately unexceptional, and it provides a framework for everything else.

Isolate the keyboards on just about anything Preston recorded, and underneath whatever’s happening in the foreground there’s usually an anchoring rhythm code. Many of these phrases descend directly from gospel music, where they help align large vocal choirs: Preston accompanied Mahalia Jackson when he was ten years old, and his solo records frequently included imaginative reworkings of hymns and spirituals. Another inspiration for Preston was Ray Charles, the R&B pioneer who employed Preston in his touring band for three years. (To hear a touch of Charles’ influence on Preston, check “Let’s Go Get Stoned” from Preston’s 1974 Live European Tour LP, which includes his spot-on imitation of Charles’ vocal and keyboard style.) Still another influence: The great New Orleans pianist Professor Longhair. That’s laced into many of his introductions and asides, including the title track of Preston’s 1971 I Wrote A Simple Song, and “Ain’t That Nothin’” from its followup, Music Is My Life.

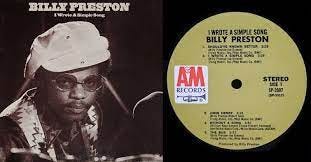

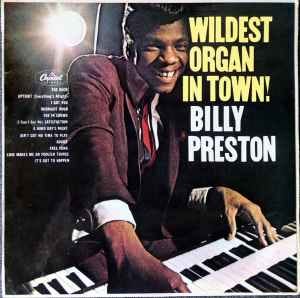

Preston’s solo discography spotlights the evolution of those signature organizing/galvanizing riffs through several distinct eras. Despite their audacious titles, two lesser-known sides from the mid ‘60s – The Most Exciting Organ Ever and Wildest Organ in Town – contain coy, carefully phrased instrumental versions of pop songs, in the general soul-revue style of Booker T. and the MGs. Through Preston’s association with the Beatles and George Harrison, he made two albums for Apple that offer a loose, surprisingly danceable approach to gospel. By 1971’s I Wrote A Simple Song, Preston incorporated clavinet and synthesizers into his sound; the Grammy-winning “Outa-Space” was the first of several instrumental hits. Meanwhile Preston’s enduring vocal singles – “Will It Go Round in Circles,” “Nothing From Nothing” and others – each contain at least one, and frequently several, thickly voiced keyboard parts that become as integral to the songs as the hooks.

Hearing Preston’s work on a bunch of recordings across years, you start to appreciate his low-key approach, the taciturn nature of his genius. Yes, he could dispense a thrilling solo pretty much on demand. But you get the feeling he found just as much pleasure working deep within the tapestry of the rhythm section, stoking and prodding the music. Being the glue.

Why yes, we have a fancy digital suggestion box. Share your favorite Underloved/Overlooked records here: echolocatormusic@gmail.com.

Please consider subscribing (it’s still free!). And…..please spread the word! (This only works via word of mouth!).

Love this part: "It’s humble work, background work, this groovetending. It involves restraint, and minute-by-minute editing. It thrives on repetition. It prizes steadiness over grandstanding. It is deliberate, and deliberately unexceptional, and it provides a framework for everything else." That's the shit.