Here’s more proof (if any were needed) that storage-unit excavation is the new A&R: A hazy reel-to-reel tape of the 23-year-old Lou Reed singing his originals “Heroin” and “I’m Waiting for the Man” and other future rock classics in a minimal, Greenwich Village-folkie style.

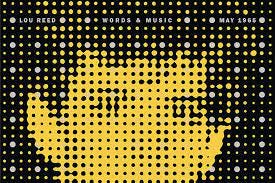

Discovered in a sealed mailing envelope amongst other artifacts after Reed’s 2013 death, Words & Music May 1965 has been digitally restored for release by the reissue label Light In the Attic. It was produced by a team headed by Reed’s widow, the performance artist Laurie Anderson, and longtime collaborators including the late Hal Willner. The set comprises the earliest known recordings of Reed compositions that appeared on albums by the Velvet Underground, one of the most influential bands in rock history, as well as later Reed solo albums. In addition to the ten songs (there are two versions of “I’m Waiting for the Man”), the package includes reflections from critic Griel Marcus as well as notes from archivists who are organizing Reed’s archive -- for future audio releases and a free exhibit currently open at the New York Library for the Performing Arts.

Reed was essentially at the beginning of his career as a musical artist when he recorded these skeletal songs, which feature just acoustic guitar, occasional harmonica and vocals from John Cale, his future collaborator in the Velvet Underground. He’d been out of college for a few years (Syracuse University, where his professors included the poet Delmore Schwartz), and was writing formula teen pop songs for Pickwick Records and playing in various post doo-wop groups. Trying to find his way.

The demos show that what Reed had, from the very beginning, was the ability to make the small time hustle seem epic – and romantic. He had a gift for immortalizing the drives, desires and motivations of those who hang out on streetcorners – and could sometimes be labeled “deviant” by mainstream society. Reed’s bracing imagery opened windows onto worlds not yet explored in rock songs; his brazen, sharply wrought characters shared all the glorious messiness of their addictions.

Reed had the lens. He had the wry, jaundiced perspective. He knew the turf. What he needed was a framework, a musical vessel sturdy enough to contain his writing. Words & Music can be seen as one moment in what was a sustained search. On it, Reed makes like a folk singer, or like a beat poet imitating a folk singer, or maybe like an outer-borough cabbie imitating a beat poet imitating a folk singer.

Which is to say: It’s folk, but meta in that Lou Reed way where there’s another level or three going on between the words and the delivery. Structurally, songs like “Men of Good Fortune” are completely straightforward – built on simple folk chords, with nods to Bob Dylan and English ballad form. The musical structure is basic basic; there are no curveballs, nothing even remotely challenging in the musical backdrops. But the visceral literary core – those phrases that made listeners feel like they were inside the heads of Reed’s characters – was fully there. Ripe for development.

As Light in the Attic founder and co-owner Matt Sullivan told the Washington Post: “When I listen to these ’65 demos, it feels like such a poetic entrance, the roots of what came next. You can hear the beat generation, you can hear him and John merging. But you can hear elements of punk rock, too.”

Listening to the irreverent renditions of “Buttercup Song,” the doo-wop manque “Too Late” and and the intoxicatingly droney Cale-sung “Wrap Your Troubles in Dreams,” you almost get the sense that Reed knows the folk template is a stretch. He’s just casting about for some magic, any magic, or a framework, or a means of conveyance. He changes the tempo in mid-tune, he changes the groove, fitfully changes his inflection from phrase to phrase.

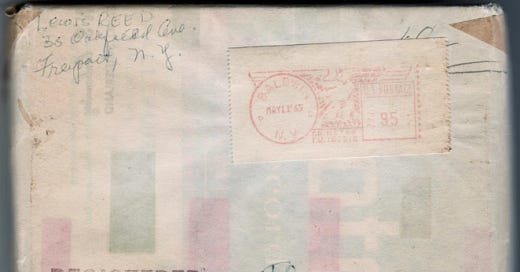

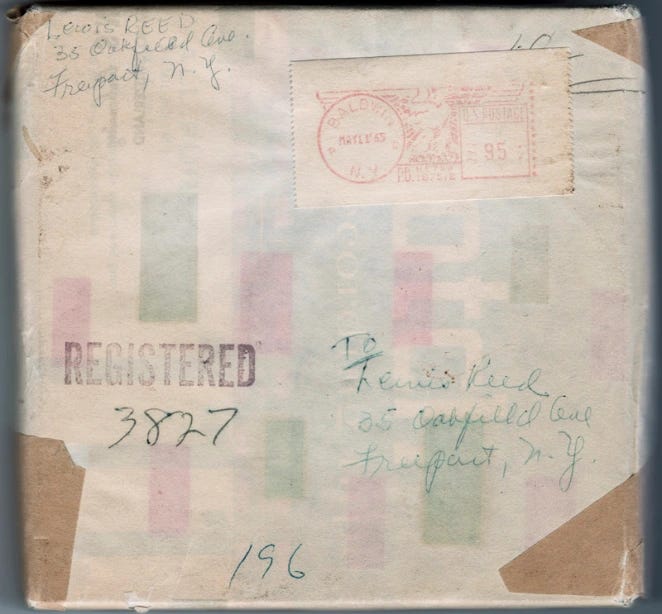

As a result of its roughshod nature, this set -- which Reed mailed to himself as a way of proving copyright ownership of the songs – is not something most Lou Reed obsessives will play on endless repeat. It’s a precursor moment to greatness, and while it shows a considerable part of Reed’s genius already in full flower, it also shows how important the stuff beyond the words was to his art.

The musical surroundings that came into focus with The Velvet Underground and Nico two years later – the thick, deftly arpeggiated guitars, the brooding washes of texture – enhanced and deepened the emotions embedded into Reed’s narratives. These elements became an atmosphere, an ethereal abstraction that could offset the brutality of the words; they created a space where his accounts of bliss-seeking and addiction spirals could unfold in ways that made them gripping. Words & Music May 1965 teaches that in Reed’s art, context was crucial.