If the guitar is your road or your religion, sooner or later you have to reckon with Pat Martino.

The guitarist, who died yesterday in his hometown Philadelphia at age 77, was a revered musician for decades – and yet still somehow remains underappreciated as a transformational figure. Coming up in the jazz world of the late 1960s, Martino gathered the forms and performance approaches that were thriving at the time – soul-jazz, organ boogaloo, wide open Kind of Blue modality, free improvisation – into a sound of transfixing complexity and emotional depth.

He blazed up and down in ways that recalibrated the music world’s notion of what’s humanly possible on the instrument – and was followed (worshipped?) not only by the jazz players who were then still processing Wes Montgomery, but by guitarists from the rock and fusion realms including Jeff Beck, John McLaughlin, Jimmy Page, Al DiMeola and (trigger warning!) Eric Clapton.

Pretty much every significant jazz or jazz-adjacent guitarist who’s been hailed since then – Kurt Rosenwinkel, Ben Monder, Julian Lage – has drawn some key influence from Martino.

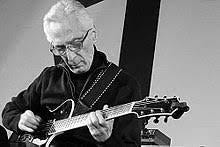

Martino had furious speed from note to note, certainly, but he avoided the showboating impulse that often goes along with that dexterity. His art was in part about the way he grouped his notes -- into compact, jaggedly cut clusters that became torrents and bouquets, and then became blurs of shape and color. He did this magic trick as a matter of routine, while contributing to the chopping crosstalk of the rhythm section. While also swinging. Mightily.

There are transcriptions out there of many of these solos. They catch the details but can’t notate a crucial stealth attribute of his music: The sound. Martino perfected a warm, rounded tone on the instrument, and understood exactly how to amplify it so his listeners felt what he was doing. Anyone lucky enough to be in close proximity to the stage when he performed probably still carries the sense impression of that sound, its purring and welcoming texture, the warm physicality of it.

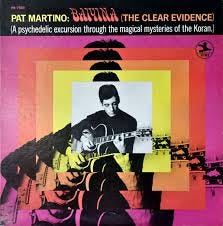

Martino’s first exposure came with organ groups – he recorded a stack of albums with Don Patterson and another stack with Jack McDuff. It was common, during this era, for musicians to release multiple albums in a year while also participating in others as a sideman. Martino’s first effort as a leader, El Hombre!, was one of two titles that appeared under his name in 1967; the following year, he released his own East! and was featured on Eric Kloss’ Life Force, McDuff’s The Midnight Sun and Soul Circle, and four (!) records by Patterson, including the oft-forgotten gem Four Dimensions.

Decades later, Martino contended that his development as a musician was at least partly the result of the relentless day-in day-out recording and touring that was common at the time. “You didn’t have time to reflect on what happened the day before,” he told me in an interview. “There was always something else coming….and I think that helped me, forced a certain amount of growth as a musician.”

That growth is audible on Martino’s records for Prestige and Muse in the early ‘70s; by then, he’d already discovered ways to utilize his technical mastery in pursuit of a relentless, always exciting visceral communication style.

And then, he did it all, all over again.

Martino’s legacy would have been secure if he’d stopped in 1977 or so. But he didn’t stop exploring until he was sidelined by a massive brain seizure in 1980 that required extensive rehabilitation. He had amnesia, did not remember familiar names or key parts of his professional life.

This gave him an intense focus on the present moment, he said later. But it also meant he didn’t remember how to play the guitar.

As he worked to regain skills, Martino did not attempt to relearn the vocabulary he’d used before. He built back better, by de-emphasizing technique. He edited out the impressive mile-long sentences that unified his old style in favor of a more lyrical approach. He leaned into blues-guitarist repetitions and harrowingly sustained single notes. As he told another journalist: “Focusing on technique reduces the artist to being a mechanic.”

The recordings from the After portion of Martino’s career, which began in 1987 with The Return, are as expansive and spirited as anything he did before. Over time he did regain fluency on the instrument, but he brandished it differently – he could sound more impulsive, was more inclined to lunge after ideas just out of his grasp. On records like Live at Yoshi’s, in a trio configuration with Joey DeFrancesco and drummer Billy Hart, Martino sounds fully immersed in the unfolding discussion. And what a range of devices he uses to bring listeners into that discussion: He might play something flashy. He might lean on a single note for a while. Whatever he does, he’s not trying to impress; considerations like “degree of difficulty” are rendered meaningless when artists are leading with the heart.

**

One thing that’s troubling to oldheads about the loss of Martino and many other foundational music ancestors: The contextual connections between artists and eras and ideas can erode or disappear with them. Martino’s discography as represented by Spotify and the other streaming services is a mess. Key titles are missing, and other key titles appear in strange reissue form with no personnel information or even the accurate recording and initial release dates.

That makes it tricky to follow the spiderwebbed thread from a towering figure like Martino back to his formative work with a lesser-known but important artist like Don Patterson, or Trudy Pitts. What we stand to lose, over time, is a sense of — and appreciation for — the sometimes haphazard ways musical scenes coalesce. We can miss out on the mulching process of art, the ways ideas are cultivated and shared amongst a group of players. Ideas that were then refined across records that bear the names of several different leaders – and then, often, got refined some more in another corner of the music universe. This inspiration circuit is not the specialized knowledge of record-store clerks; it’s the history behind the history as presently represented. Future generations should be able to trace it, link by precious link.

Why yes, we have a fancy digital suggestion box. Share your favorite Underloved/Overlooked records here: echolocatormusic@gmail.com.

Please consider subscribing (it’s free!). And…..please spread the word! (This only works via word of mouth!)

Thank you for this fine piece about Pat. I was the pianist on “Pat Martino Live!” He was a road warrior like Miles, his band was his family. I had a unique relationship with him because of my classical/new music background in composition. We mentored each other! And always in touch, the mutual respect and affection grew and grew.

Pat Martino Live was reissued digitally also as “Head and Heart”