Another Dispatch from the Analog/Digital Fault Line

Talking Record Store Day in the Context of ChartCipher

Last week brought good news to music lovers, in the form of another impressively gargantuan list of vault gems, reissues and collectibles that will arrive for sale as part of the next Record Store Day on April 20.

There are superstars (Willie Nelson) and influential talents (Mudhoney) and live records that catch big names at crucial moments (The Doors’ Live at Konserthuset, Stockholm, September 20, 1968). To make fetishizing easier, our friends at Rough Trade Records compile a routinely updated list of confirmed releases. Almost all of them will be available on vinyl.

The twice-yearly RSD event (the other one is usually on Black Friday in November) has grown from a loosely coordinated indie-store traffic builder into a resolutely genreblind celebration of music discovery. Its emphasis on unreleased material has accelerated an industry-wide scramble for archival gold: Were it not for this type of organized initiative, many lesser-known near-classic records would likely never return to circulation.

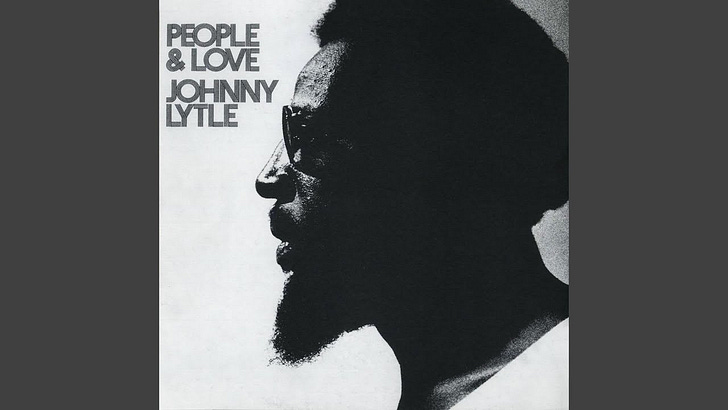

One example just happens to be my obsession of the week: Johnny Lytle’s deep soul-jazz gem People and Love (Milestone, 1972). This five-song set isn’t an RSD title, but it has received an RSD-style revival. The work was remastered for streaming last year – that’s where I first encountered Lytle’s slow-burning version of the Stylistics’ “People Make the World Go ‘Round,” which benefits greatly from the steadying presence of electric bassist Bob Cranshaw. Next month, Jazz Dispensary is bringing out a vinyl version for its Top Shelf audiophile series, cut from original analog tapes and pressed on 180-gram vinyl in limited quantities. It’s an enthralling listen, shaped by vibraphonist Lytle’s extraordinary fluidity and his group’s attention to open-canvas groove detail. Can’t wait for the vinyl.

When the history of this strange period in music is written, Record Store Day will get credit not only for sparking interest in the easily overlooked talents of yesteryear – but for developing (and sustaining) a market for context-rich, thoroughly researched and lovingly packaged titles.

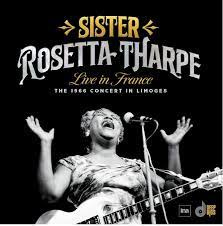

Among the ones dropping in April I’m excited about: Live in France: The 1966 Concert in Limoges, a solo performance by the legendary Sister Rosetta Tharpe; a Sun Ra compilation called Pink Elephants on Parade, which features Arkestra renditions of tunes from the Disney songbook; the long-overdue return of the cult classic Little Joe Sure Can Sing, spotlighting Joe Pesci’s short career as a crooner.

It’s impossible to come up with broad generalizations that apply to all of the names on this delightful RSD list. But here’s one safe bet: None of the artists made creative decisions about the music based on the findings of ChartCipher.

ChartCipher is among the analytic firms using digital technology to evaluate, down to the tiniest of attributes, what makes songs hits on the Billboard Streaming chart. Its yearly survey looks at “Compositional, Lyric and Sonic Trends,” as the preface of the free “preview” version of this year’s report explains: “ChartCipher provides deep analytics reflecting the songwriting and production decisions behind today’s most successful songs. Using AI, ChartCipher extracts granular data for the compositional, lyrical and sonic qualities of songs and delivers deep, real-time insight into the qualities shaping today’s hits.”

DingDingDing! AI! Are we surprised?

I learned about this tool – which, of course, has dual use as both a gauge of recent trends and a prescriptive guide for those chasing future hits – from last week’s post from prominent YouTuber Rick Beato.

Like Beato, I’m fascinated by the lanes of inquiry: There are graphs dedicated to Timbre/Tone Quality that indicate how, since 2019, songs with “brighter timbres” have been on the rise. (We’re eating more beets!) There’s another data set, which is unfortunately behind a subscription paywall, that offers a chordal “census” analyzing the types of chords and the frequency of their occurrence in hit songs. (Anyone who’s a ChartCipher subscriber and is inclined to share this one in the comments will heretofore be considered a hero in these parts….).

The picture that emerges is exhaustive and microscopic, exciting and banal at the same time. The data maps boil down aspects of musical creativity to binary on/off decisions. They measure all the traits and none of the mysteries. The graphs, eagerly gobbled up by the remaining label executives with talent-interfacing responsibilities, suggest that the slightest choices a songwriter (or, as is often the case, a songwriting team) makes can push a track closer to hit song territory. As if.

I want to poke holes in the methodology, in the demand for such evaluation, in the premise behind the analysis. That would make for a fulminating torrent of vaguely pissed off words – the lunatic rantings of yet another greybeard tiresomely prattling on about how the analog world was better for music. That song by the Police says it better: “De Do Do Do, De Da Da Da.”

Not sure why, but the music of the Police pokes bigger better holes in the notion of data-guided composition than any journalist ever could. Something about the intensity level? The brainscrambling time-chopping drums of Stewart Copeland? Reading about ChartCipher on song length (getting shorter, see Tik Tok) and tempo and harmony led me to seek solace in “Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic,” the single from the fourth Police album Ghost In the Machine (1981).

My goodness. Here we have a pop ode about unrequited love that trashes every metric of hit song science in just over 4 delirious minutes.

It’s fast – 162bpm – but it’s not the same kind of fast the whole way. (The verses move in a kind of hazy halftime, and the refrain erupts into torrid backbeat-studded shout-chorus swing.) At the end of the first chorus, around 00:49, there’s a chordal swerve and accompanying vocal-harmony array that’s closer to Alban Berg than the Beach Boys. Every section of the song has its own set of instrumental “signature,” each contributing to the overall sense of (hurtling) motion in a different way.

Then there’s the (extended) bridge. It reverts back to halftime, and after a clear-out we hear a single (guitar?) note hanging in the upper register, “glue” in the form of a disquieting through-line. This sustains for the duration, through Sting’s tortured and oddly phrased confessional lyrics and into a synth-driven crescendo that ramps up tension for nearly thirty seconds until a stoptime break exactly at the 2:00 mark. That brings back the chorus, in all its thrill-ride glory.

There are at least four extremely intentional crescendos in this little piece, building from calm valleys to medium peaks to mountaintop shouts. When was the last time you encountered even one or two examples of dynamic contrast like this on a streaming hit?

There are way more than four demonically fitful drum fills on “Every Little Thing,” each one contributing directly to the propulsion. The trio would have expected these, in those spots, but could not have anticipated the surge they would bring. Somehow they get it; we hear them jumping on that runaway train time and time again. When was the last time you encountered something so galvanizing on the drum track of a streaming hit?

Like just about every title in that RSD list, “Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic” speaks to notions that seem to be becoming exotic in music making – the role of instinct, the physical tremors that happen when people are in a room responding to each other. How the kinetic energy enhances the cleverness of the writing. And on and on.

“Every Little Thing” catches a golden mean between the headfirst lunge and the deliberate, sometimes ornate schematics of pop craft. You feel the human engagement literally every second. These musicians are immersed in chasing down — but, crucially, not mapping — the mysteries of the song’s vibe and structure. They need no help from the algorithms.

A masterful essay. The way we you connect the dots here is vitrousic.