All Things Must Pass (Again)

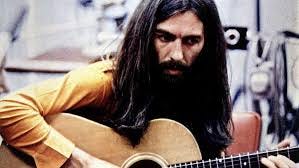

A window into the creative spirit that led to George Harrison's iconic solo album.

Did we need a new and improved mix on All Things Must Pass, which turned 50 years old in 2020?

George Harrison thought so. In interviews at the time of the album’s 30th anniversary, he lamented the excessive reverb used by producer Phil Spector.

Dhani Harrison, George’s son who oversaw the elaborate new 50th anniversary set, recalled his father describing the reverb as “too much.” In a recent interview, he explained that he and engineer Paul Hicks devoted several years to de-gooping the mix, endeavoring to retain its essential character. “Bringing greater sonic clarity to this record was always one of my father’s wishes and it was something we were working on together right up until he passed in 2001.”

The new mixes accomplish that goal: They’re a sharper, and just a touch brighter. The interwoven latticework-like guitar parts – from Harrison and the many guests who participated – are rendered with a sonic precision that mirrors the precision of the playing. The overall mix is not a radical overhaul: Where some after-the-fact reworkings completely mess with the memory of a record, this one just encourages deeper listening, revealing details that had been previously blanketed.

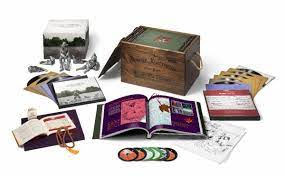

And….the new mix is possibly the least interesting aspect of this new release, which is offered in a confusing array of configurations at cleverly tiered price-points. With Super Mega Deluxe you get prayer beads.

The unreleased material starts with the project’s first session, when Harrison, Ringo Starr and Klaus Voormann tracked simple songwriting demos of 15 original songs. There’s a disc of previously unreleased solo Harrison demos, and then a disc of jams and rehearsal takes involving the astonishing supporting cast that floated through the sessions – Billy Preston, Eric Clapton, Dave Mason, Peter Frampton, Gary Wright of Spooky Tooth and others.

Harrison had lots of songs saved up when the Beatles dissolved in April 1970. Some reflect the melodic grace and writerly discipline of his former band, and some are wild left turns – rambles and marches and meditations on spirituality that have no nearby corollary in pop history. One marvel (among many) of this album is the way these disparate pieces fit together, with spangly radio songs (like “My Sweet Lord”) juxtaposed against darker, more acerbic commentaries (“Isn’t It A Pity”) juxtaposed against hallucinatory evocations of bluegrass and roots music.

The “Session Outtakes and Jams” disc offers clues about the routes Harrison took to create such a freewheeling, unselfconsciously expansive experience. He was just emerging from what, by all accounts, was the wrenching tension of the Beatles demise; one of the delights here is a rehearsal take of “Wah-Wah,” his irreverent appraisal of the band’s late-stage business meetings.

When Harrison began recording as a solo artist in May 1970, he was, understandably, ready for a change. He drew on the support of a broad community of musicians who understood what he’d just gone through – it was a news story, after all – and were ready to help him move beyond it. They were also, inevitably, curious to hear where Harrison might go, and how they might help him get there.

That put Harrison in the unusual role of field general for an all-star team. Listening to the rehearsal takes and mostly brief jams, the first thing that registers is the looseness: Harrison had an easygoing way about him, and in his quiet directions and his subtlety-forward playing, he conveys a highly specific non-verbal sense of the tone he’s seeking. He wants a mojo reset, a joy infusion. As he dials down the klieg-light frenzy that surrounded the Beatles, he gravitates to slight gestures and simple songforms. He’s at the beginning of a journey, and the session takes show what that feels like: There’s a wonderful, attentive sense of blank-slate creativity in the air, and it’s shared by all involved. Harrison is just trying stuff out, and at this point in the process he doesn’t stop to decide if the experiments are successful or not. Through the temperament of his playing, he cultivates a spirit of craft collaboration: We hear him gingerly leading the musicians into the flyspeck details of his gorgeous, unconventional songs.

Of course the songs themselves evolved during the making of All Things Must Pass. But far more interesting, from a care-and-feeding-of-the-muse perspective, is the environment Harrison created from the first day, the environment that’s audible on the unreleased discs. His stardom meant that this couldn’t be a cloistered process, and he rolled with it. He transformed friends and casual visitors into collaborators, got them on the same page and got sparkling contributions them. He gathered those into a deeply thoughtful, endlessly refracting multi-faceted work that is alive with joy and abundance – and a refreshing absence of external pressure. He took what could have been a media scene and turned it into a hang, and turned that into music for the ages.

Why yes, we have a fancy digital suggestion box. Share your favorite Underloved/Overlooked records here: echolocatormusic@gmail.com.

Please consider subscribing (it’s free!). And…..please spread the word! (This only works via word of mouth!)

"Dhani Harrison, George’s son who oversaw the elaborate new 50th anniversary set, recalled his father describing the reverb as “too much.” In a recent interview, he explained that he and engineer Paul Hicks devoted several years to de-gooping the mix, endeavoring to retain its essential character." Clearly the restoration is a work of love ... listening to it now. It was great before ... and it's even better now.